The headlines coming out of Texas are stark. “Texas coronavirus cases top 1,300 from child care facilities alone,” reads a CNN article from July 6th. Similarly, as child care providers have opened widely across the nation, the media has picked up on COVID-19 outbreaks in child care centers from Oregon to North Carolina.

These cases are undoubtedly newsworthy. But we’re thinking about them all wrong.

The question that parents and practitioners really want to know is this: How safe are child cares? Or, put another way, how likely is my child (or am I) to catch COVID-19 from a child care center? In order to know that, we need to be able to answer how much transmission is occurring WITHIN child care centers? Until we ask the right questions and demand the right data, we’ll be stumbling in the dark.

Think about two scenarios.

In scenario A, a child care teacher unknowingly becomes infected with COVID-19 on a Saturday while at the gym. She goes to work on Monday. On Tuesday she begins to feel unwell and calls out sick. By Friday she has a positive COVID-19 test in hand. No one else in the center becomes infected.

In scenario B, a child care teacher unknowingly becomes infected with COVID-19 on a Saturday while at the gym. She goes to work on Monday. On Tuesday she begins to feel unwell and calls out sick. By Friday she has a positive COVID-19 test in hand, but on Monday she had infected two other teachers and three students, who in turn infected others before the initial positive test came back.

In both scenarios, there was a positive COVID-19 case in a child care facility that would need to be reported to the authorities. In one scenario, no transmission occurred. In the other, a cluster formed. To accurately assess risk, we have to be able to understand whether most cases fall closer to scenario A or scenario B.

As Steven Barnett, Senior Co-Director of the National Institute for Early Education Research, put it in an interview, we can figure this out by using context most journalists currently aren’t using. For instance, it’s instructive to compare the percentage of infected children and staff in child cares against the infected percentage in those age populations generally.

Take Texas. There are hundreds of thousands of young children back in Texas child care centers. The 441 reported infections among children represent a tiny fraction. If that fraction was significantly higher than the infection rate of all same-aged Texas children (including those not in child care centers), that suggests the centers are playing a role — and vice versa.

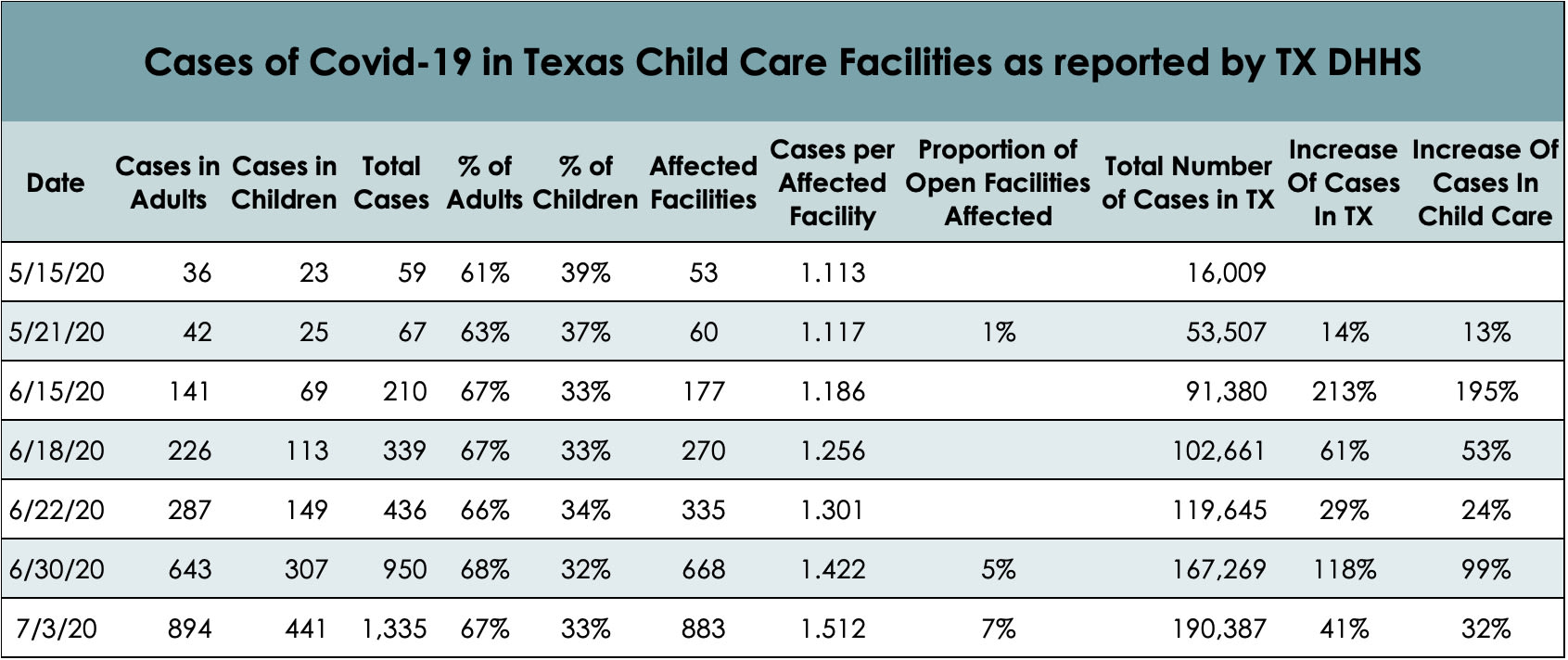

Economist and author Emily Oster expanded on this idea in a recent newsletter. Oster writes that taking into account a full suite of factors — the denominator (how many total children and staff are in the open centers), relative risk, amount of clustering, and rate of increasing cases — may paint a different picture. While no one wants to see any cases in child care, Oster notes that particularly when it comes to the rate of increase in Texas, “it doesn’t look like [child cares] are outpacing the general population,” suggesting the viral activity may be primarily driven by Texas’ overarching public health crisis (Oster provided the below table, created by Ashley Kubisyzn).

As Barnett explains, not all mitigation precautions are created equal, and we need to drill down on which ones are the most important. For instance, if nearly all centers with cases didn’t have strict exclusion policies for staff that were feeling unwell, or if they didn’t modify drop-off and pick-up procedures to limit the number of congregating adults, that would suggest a correlation.

On the other hand, if centers with mandatory temperature checks were equally as likely to end up with a case as those without, that might suggest such checks are a less impactful intervention. We have, unfortunately, created a massive natural experiment. Absurd as that choice was, we should at least take advantage of the opportunity to hone our strategies.

It’s also incumbent on child care advocates to keep a level head. While there are a ton of wonderful journalists out there, on some level, ‘the media’s gonna media.’ Or, as Barnett puts it, there is “very little incentive in reporting to cover solutions as opposed to problems.”

North Carolina provides a good illustration. North Carolina has started twice-weekly updating a public report on outbreaks of five or more cases in child care and schools. Despite an overall rising case count, as of July 7th there are only seven reported clusters in child care centers.

You won’t see any articles with the headline, “99 Percent of North Carolina’s Open Child Cares Have No Clusters,” though.

Similarly, there has been little to no reporting noting the continuation of encouraging news about young children themselves. For instance, the fact that so many more staff than children are showing infection — despite centers having many multiples more children than staff — is yet further evidence of young kids’ relative protection from the virus (as well as the need to vigilantly limit adult-to-adult contact). Moreover, outbreaks are rarely starting with children, and child cares overall aren’t hotbeds, especially compared to other settings.

As Dr. Sean O’Leary, one of the authors of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recent guidelines for school reopening, said in a recent interview with The New York Times: “Here in Colorado, I’ve been following our state health department website very closely. They update data every day and include the outbreaks in the state they are investigating. As you can imagine, there are lots and lots in long-term care facilities and skilled nursing homes, some in restaurants and grocery stores. There have been a total of four in child care centers, and we do have a lot of child care centers open. In almost every one of those cases, transmission was between two adults. The kids in the centers are not spreading Covid-19. I’m hearing the same thing from other states, as well.”

States aren’t doing journalists or advocates any favors, of course. Data collection is variable, to say the least. Some states produce regular public reports, others produce none. The threshold for reporting an “outbreak” varies: North Carolina says five or more (that can be reasonably linked), Colorado says two or more. Detail levels vary widely.

While Yale University is running the one major systematic study of COVID-19 spread in child care and will release data soon, even that study is insufficient on its own. The researchers did their data collection between May 22nd and June 8th, and so the results won’t reflect the real-time and ever-changing conditions on the ground, particularly the spiking community transmission in many southern states. Economist and author Emily Oster has resorted to crowdsourcing cross-state data.

If the early learning sector is going to respond to these bitterly-learned lessons and maximize our risk reduction, we have to insist on centralization of case data and common definitions of terms. Without good data, we’re left trying to piece together a story out of smeared page fragments. Ideally, governors and their relevant cabinet secretaries would step up and work together. If not, Barnett suggests this may be a place where Child Care Resource & Referral Agencies can play a role.

The cold reality is that there are going to continue to be COVID-19 cases in child care settings, and there will even continue to be the occasional outbreak. Undoubtedly, the breathless headlines will continue. That doesn’t mean child cares are unsafe, it means we’re living through a pandemic. But we can’t figure out what actions to take to reduce the incidence — and, at the extreme end, whether we need to close centers in areas with raging local epidemics — without better questions, better data and better context.

(P.S. None of this matters much if half of the child care centers close and the other half can’t afford to put effective precautions in place. Congress needs to fully fund child care!)