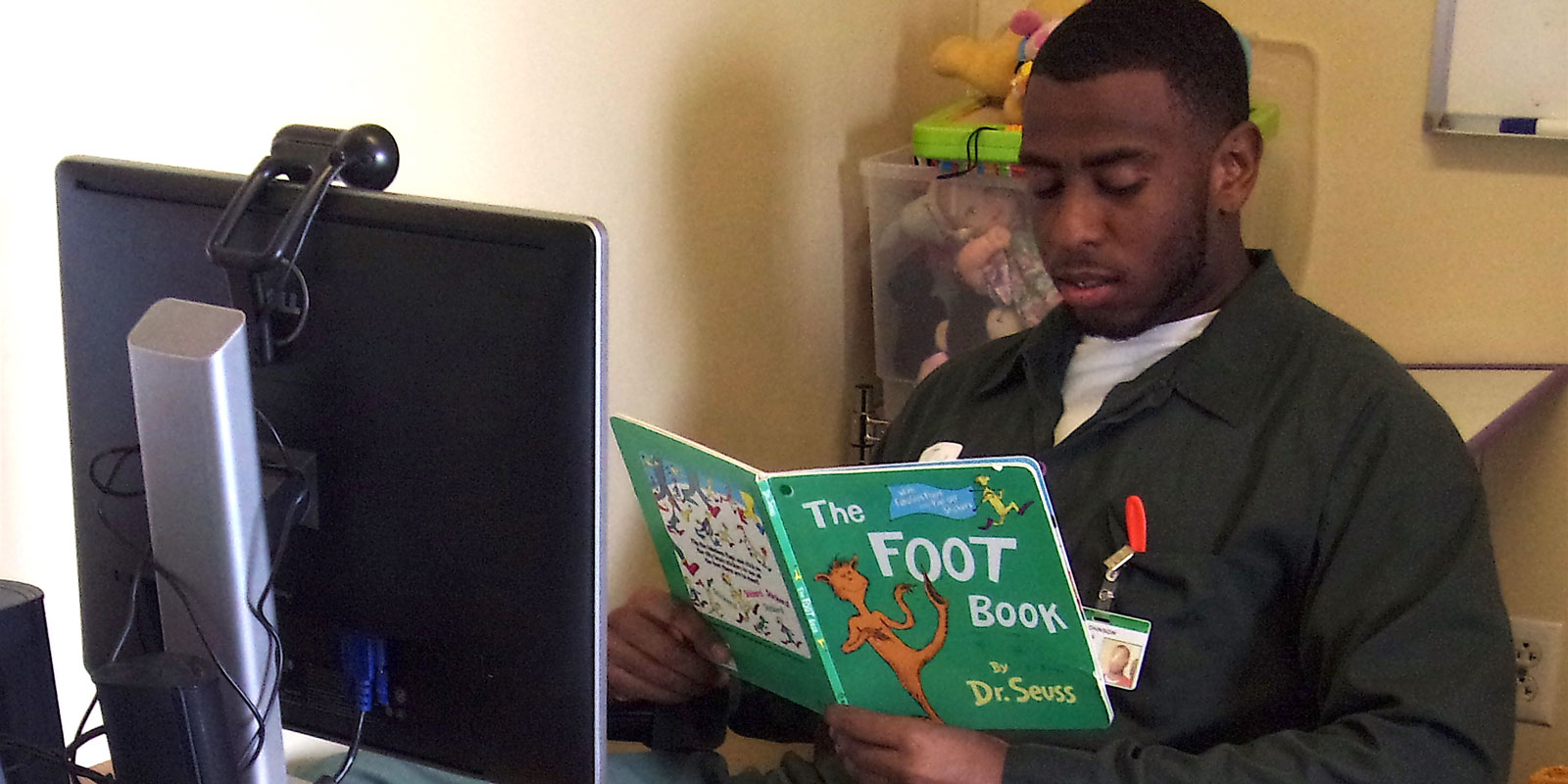

E—- Johnson, 29, is a sheet metal worker. “It’s a good job because of the union,” he says. He hopes to return to this job as soon as he leaves prison, perhaps as early as next summer, but what he’s most looking forward to is reuniting with his girlfriend and their three children: a 12-year-old daughter, a 6-year-old daughter and a 4-year-old son. To prepare for that moment, Johnson is dedicating time and effort to the parenting education provided by the Family Connections Center, an innovative program run by the New Hampshire Department of Corrections.

Johnson’s daughters and son are three of the 2.7 million children (1 in 28) who currently have a parent behind bars, according to the Pew Trusts.

The Family Connections Center teaches parenting skills and addresses general child development. The program is geared to address the unique struggles of families with an incarcerated parent. Participation earns Johnson an “earned time credit”: reduction of time served as well as extra opportunities to engage with his children and to take more classes, but he doesn’t just do it for the perks.

“My childhood wasn’t the best,” he says. “My parents were addicted to drugs. They weren’t always around. These courses make me think about myself when I was the age my children are.” Johnson grew up in Springfield, MA, often in the care of his grandmother, who had seven children of her own.

Program supervisor Tiffani Arsenault teaches the classes. “She breaks it down scientifically,” says Johnson. “What’s happening inside their minds during infancy, through the toddler years and on up through adolescence.”

In a facility that holds 600-700, Arsenault works with 80-100 fathers, who voluntarily attend weekly programs. In addition to the parenting course, Johnson is taking a sequence of classes built around the videos and handouts from the Mind in the Making curriculum based on the book by the same name by Ellen Galinsky, which posits self-reflection as a pillar of improved parenting. “How are you supposed to instill focus and self-control in your kids if you never developed those skills yourself?” asks Arsenault. “I love Mind in the Making because it gives them that foundation they need.”

“The unique aspect of this program is that it promotes skills in adults and children,” says Galinsky. “It makes brain development science accessible for all ages and it’s encouraging to hear that New Hampshire views prison as more than punishment. It can simultaneously be a learning community for parents and their children.”

Arsenault says she’s had to grow into the role of conducting training for parents. “When I started, I wasn’t a mom yet,” she says, “and I never put much thought about who goes to prison or how many families are affected by incarceration.” After nine years on the job, having the opportunity to hear their stories and get to know some of their families, she says “They’re all just doing the best they can, like the rest of us.… The families affected by incarceration are our families, friends, neighbors, community members and so on. We all experience hardships.”

[Watch an in-depth report on Family Connections Center]

She describes the Family Connections Center as “an opportunity for self-betterment. “They’ve had a lot of adverse experiences. They’ve burnt a lot of bridges. But they’re learning the value of consistency. And they’re trying to be better dads.”

Since 1998, the program has offered support and education for approximately 6,700 kids of incarcerated parents; this number is probably low because of the way in which data have been collected and maintained. It operates at all three of the department’s prisons. In addition to the course work, the Family Connections Center provides opportunities for the children to visit their parents via video and for family fun days, which are a field day of sorts, including a barbeque and games. There’s even a summer camp—YMCA’s Camp Spaulding—that allows kids to spend two full days in the prison with their incarcerated parent. It’s inspired by Hope House DC.

The approach is backed by research. According to a 2005 study in the Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, “There is evidence that maintaining contact with one’s incarcerated parent improves a child’s emotional response to the incarceration and supports parent-child attachment.”

According to New Hampshire Department of Corrections Commissioner Helen Hanks, ”Family Connections Center provides a critical resource to men and women who are parents and incarcerated in a multitude of ways by assisting in navigating the impacts of the incarceration on their children, advancing their parenting skills and creating access to communication through reading, video visits and other creative projects.”

Unfortunately, the New Hampshire model is still not common. A report by Bureau of Justice Statistics found that only 53 percent of incarcerated parents had spoken with their children over the telephone since admission, and just 42 percent had had a personal visit.

In a video featuring the Incarcerated Nation Campaign, Shaquille Muallimm-ak recalls his father’s prison sentence, during which time no contact was permitted, saying, “It felt like somebody died,” adding that he felt like he, too, was incarcerated.

Johnson tries to be honest with his children about how he became incarcerated. “It’s even okay with me if they talk about it in school,” he says. “I’m not the only father in jail.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.