Julie Leff can pinpoint the moment when she knew Roger Brooks was the right person to lead Facing History and Ourselves.

Leff, the board chair and a former history teacher, was standing on the Amtrak platform with Brooks in 2015, shortly after he became CEO, waiting for the train to take them to his very first meeting with donors. As she remembers, “He turned to me and said, ‘Everything I’ve done in my life has led me to this point.’”

Did the donors make a significant contribution? Yes, but to Leff that’s not the point. “He sees this as his calling,” she says.

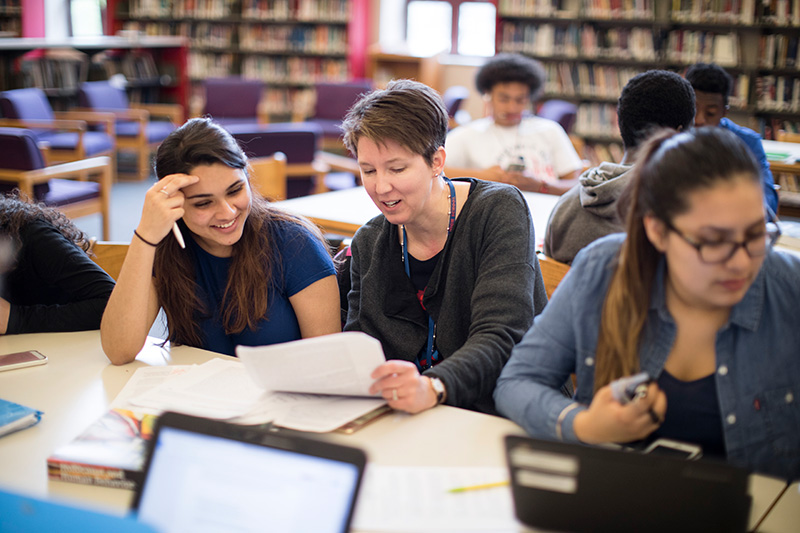

Facing History equips high school and middle school teachers to bring history alive through engagement with primary sources (including firsthand accounts) and guided conversation. Under Brooks’s leadership, the organization has grown to the point where it now trains 100,000 U.S. teachers and reaches millions of students. More significantly, it has pioneered a new approach to history education, embracing current events and personal identity to achieve a deeper understanding.

Teachable Moments

“We ask students to think about their identity in relation to a community,” Brooks explains. “Identity maps are complex. They turn on more than one axis. What other identities can you be part of?” He describes a classroom where cliques are fixed and impermeable until two students realize they have something in common—say, playing the piano—and the walls separating people come tumbling down.

Brooks came to Facing History after serving as Dean of Faculty and Chief Academic Officer at Connecticut College, where he also held the Elie Wiesel Professorship in the department of Religious Studies. He took the reins from Facing History’s founder and longtime leader, Margot Stern Strom, a trailblazer in the movement to teach the Holocaust through encouraging students to walk in the shoes of others. “Stern Strom’s insight,” Brooks says, “is that history can be used to teach what it means to make good choices.”

The Holocaust carries great meaning for Brooks, as a subject he researched and taught for decades, and as a personal matter—as an American Jew who grew up in Minneapolis in the 1960s, when “Gentiles Only” signs remained a fresh memory. At the same time, upon meeting with teachers, he realized that other subjects, including current events, could also spark meaningful dialogue and what he calls historical thinking. “Skills like recognizing cause and effect and building an argument matter whether or not you become a history major,” he says.

Facing History has made racism in America a central topic of its curriculum development. Just as the Holocaust arose out of a long history of anti-Semitism in Europe, there are historical factors to consider when we watch TV coverage of a police officer shooting an unarmed black man.

Take, for example, Facing History’s four-part lesson plan that accompanies the documentary film, The Murder of Emmett Till. The subject engrossed the history class at Overton High School in Memphis so much that they researched lynchings in their area and tracked down the great niece of one of the victims. They pushed for a historical marker at the site where Ell Persons was lynched one hundred years earlier. Khari Bowman, then a senior, said “I wouldn’t have discovered activism without this experience because I’m a shy person. It’s brought out someone who is outspoken and who is excited to share knowledge with others.”

- 94% of students reported that they gained skills relevant to analyzing world events.

- 81% of students feel they are more capable of recognizing racism, anti-Semitism and prejudice.

- 82% of students have stood up to someone who made a bigoted or racist comment. (“When they can articulate why offensive comments are damaging, they realize they have agency to make it better,” says Brooks.)

- Students register to vote at a rate that is 20 percentage points higher than the average for U.S. citizens their age. (“Pulling the levers of power includes pulling the levers in the ballot box.”)

Given Brooks’s background in higher education, how did he adapt to a nonprofit focused on younger students? “Most of what happens is the same,” he answers, downplaying the difference between academia and nonprofit life, citing the common demands of collaboration and problem solving. He also credits the commitment of his team—“not just the program staff, but development, IT, HR, everyone fully believes in standing up against bigotry and hate. They live to make the world better.” Leff points out that Brooks played a large role in assembling this team.

The COVID Pivot

The present moment has challenged Brooks and Facing History like never before. “At various points,” he recalls, “People have told us that our mission matters ‘now more than ever,’ but this time it’s especially true.”

For one thing, the crisis is exposing “the meanest and most despicable fault lines in our society.” Mentioning horrific discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans, Brooks marvels that in this day and age, people are still asking Can we trust the immigrants?

“Stress always releases bias,” he states. “Our universe of obligation is supposed to grow as we get older, but the pandemic shrank it, as people worry about nothing else besides themselves and their families.” Case in point: The Great Toilet Paper Shortage of March 2020.

Another challenge struck at Facing History’s core method for training teachers—its popular and transformative in-person workshops. The organization was already starting to embrace online platforms, but the pandemic has meant accelerating the shift.

Brooks reached out to the teacher community, asking What do you need? More than a thousand responses came down to a twofold request: more tools for teaching remotely and curricula for teaching social-emotional learning.

Facing History launched a virtual Community Conversation Series, starting with actor and activist George Takei (best known as Star Trek’s Lieutenant Sulu) discussing his family’s wrongful incarceration during World War II and ways to confront today’s anti-Asian racism.

The hate unleashed by the pandemic targets more than Asians, of course. Jews, the perennial scapegoats of history, are also in the crosshairs, and Brooks is prepared. Late last month, the Facing History office in Memphis partnered with three local organizations to present a screening and panel discussion of Viral: Anti-Semitism in Four Mutations via the PBS online platform OVEE, and similar events are in the works.

“We all get to decide what goes viral,” asserts Brooks.

Facing History provides teachers with detailed lesson plans that include questions for provoking respectful discussion about potentially divisive topics.

- Understanding #TakeAKnee: What does it mean to be patriotic? Can one love and support one’s country while simultaneously expressing anger toward and protesting its injustices?

- Responding to Pittsburgh: The synagogue attack in Pittsburgh is disturbing and painful to learn about. It prompts us to ask many questions, some of which may not have an answer. What questions does this event raise for you? What feelings does it provoke?

- “Unite the Right” in Charlottesville: Why in both 2015 and 2017 have acts of violence prompted increased scrutiny and debate about Confederate symbols and monuments? Is there a relationship between these monuments and symbols, the ideas they represent and the acts of violence that occurred?

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.