Recently, the anthropologist James Peacock III told me about the night in 1964 when his newborn daughter Louly had swallowed amniotic fluid and was blue all over. The hospital somehow reached a young pediatrician who had been at the movies, but rushed over and massaged the infant until dawn, when she finally turned a thriving shade of pink. “She’ll do fine,” Dr. T. Berry Brazelton told the anthropologist.

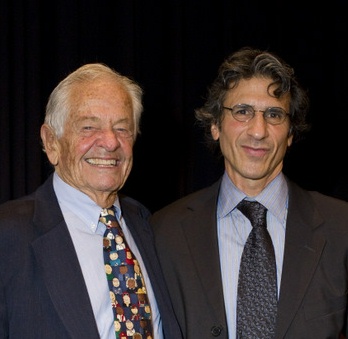

In the first of this two-part interview, Dr. Sparrow delves into the legacy of the founder and describes how Touchpoints is carrying on.

Mark Swartz: Dr. Brazelton seemed to save babies’ lives wherever he went.

Dr. Joshua Sparrow: When I traveled with him around the country and around the world, people in airports and hotel lobbies, flight attendants, taxi drivers and doormen would stop him and say, “You saved my life.” They were referring not only to their children, but also to themselves, as parents. “You were right there with me, taking care of my baby with me. I wasn’t alone. You understood me.”

Swartz: What were his greatest contributions to your field?

Dr. Sparrow: His greatest contributions? Understanding newborn behavior, individual differences at birth, the earliest infant-parent interactions, the extraordinary pace and neuroplasticity of the brain during the first three years and the Touchpoints model of human development. There were multiple fields that wouldn’t be here without him. In fact, Margaret Mahler, renowned child psychoanalyst and child development theorist, admitted to him that she had never actually observed babies under six months. The fields of infant mental health and developmental-behavioral pediatrics grew out of his research, as did the child life specialty, which began at Boston Children’s Hospital with his partnership with Myra Fox. Brazelton’s work with babies who were born with challenges at birth—born without sight or without hearing or without limbs—led him to propose the concept of neuroplasticity, the incredible ability of the very young brain to restructure itself to compensate for all kinds of challenges.

Swartz: Although Professor Peacock and Dr. Brazelton didn’t stay in contact after his daughter was born, it’s interesting to me how Peacock’s field, cultural anthropology, shaped Touchpoints.

Dr. Sparrow: Berry studied newborn babies around the world. For example, on the Gotō Islands, quiet fishing islands in Japan, on the mountains of Chiapas Mexico, where he observed Zinacantán babies and families, and in Kenya, with the babies of the Gusii people. He found that, in addition to individual differences from one newborn to another, there were differences between groups; during pregnancy, the environments within the womb and around the mother are different. On the Gotō fishing islands in Japan, the mothers were quiet and smooth in their movements as they spent their days sitting on the beaches mending their husbands’ fishing nets. The Gusii people were physically active all day, planting, harvesting and herding. The differences he observed in their newborns’ behavior he believed were the result of their prenatal experiences. These primed them both to be ready for the environments they were born into, and to shape their caregivers’ caregiving behavior.

Swartz: Along with his other accomplishments, he also found time to mentor the next generation of practitioners and advocates: you, for instance.

Dr. Sparrow: Not just one generation, but several. And not only practitioners and advocates, but renegades and rebels, researchers, leaders and change makers. I am just one of many, many fortunate students of Brazelton’s research whom he generously invited to stand on his shoulders.

Swartz: One of the Touchpoints principles—“Value disorganization and vulnerability as an opportunity”—really jumped out at me. What do these words mean to you?

Dr. Sparrow: The Touchpoints model of human development is similar to other change processes: for example, in biology, the physical sciences, within individuals, families, classrooms, organizations and communities. Each new developmental step or capacity emerges during or after a period of temporary developmental disorganization and vulnerability. For example, the birth of a new baby is disorganizing for any family, and everyone is more vulnerable, temporarily.

Yet the process of getting to know who this unique new individual is, of learning how to be this baby’s parent, yields new strengths and skills. During these periods of vulnerability, risk of developmental derailment is heightened, but can be prevented with anticipatory guidance provided within strong and trusting relationships. Brazelton called these disorganizing periods “Touchpoints,” because they are points in time for touching into the family system to offer the extra support needed for reorganizing the child’s capacities and resources for the next developmental step.

In part II of this interview, Dr. Sparrow explores the present moment and the consequences for young children.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.