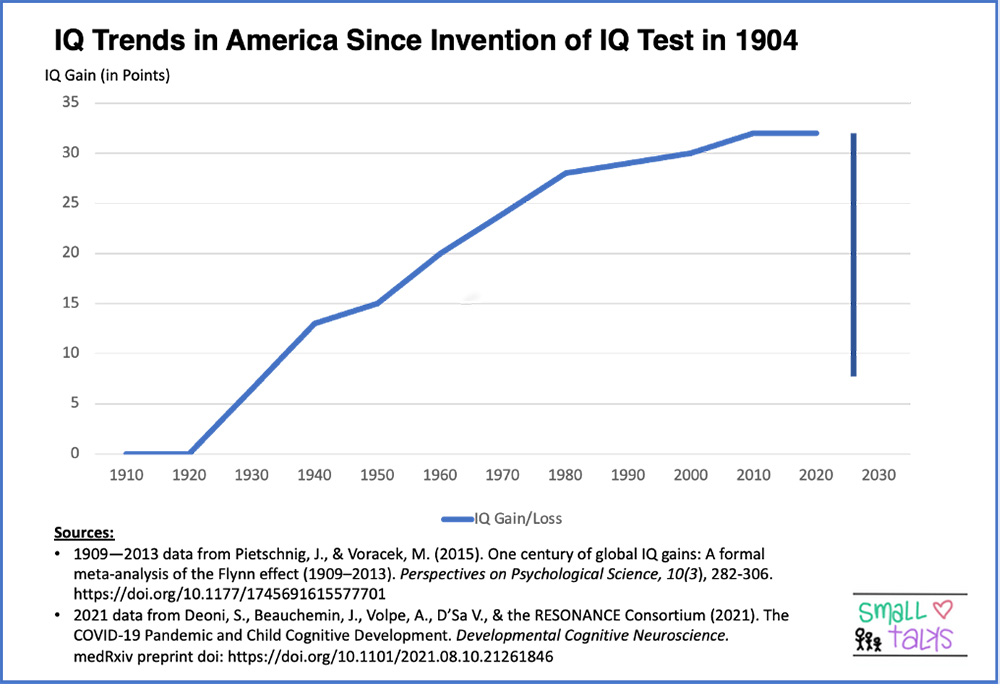

During the pandemic, life expectancy has trended down. Equally troubling, and far less discussed, is a recent decline in average IQ. This is the first time IQ is dropping since the intelligence test was invented in 1904. We as a human species may be getting dumber.

Despite criticisms and limitations (according to its own inventor, IQ does not fully assess intellect), this measure of intelligence has been widely used. It remains correlated to later education outcomes. IQ scores have steadily increased—a phenomenon called the “Flynn effect”—by three IQ points or more per decade. That is, until 2020.

Two recent studies, one by Brown University and five other universities, and the other by Columbia University, both concluded that cognitive development is declining. They have found that babies born during the pandemic have lost 22 points in IQ, or the equivalent of 70 years of IQ gains. The impact is more pronounced for boys and children of lower socioeconomic background.

How can we measure IQ in babies? Researchers at Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital used a methodology called the Mullen Scales of Early Learning. They scored cognitive and motor development of 700 children between ages 3 months and 3 years, based on developmentally appropriate benchmarks. They then converted those scores into IQ numbers.

There were signals before the pandemic that IQ may be trending down, but this magnitude of a drop is unprecedented.

Why is IQ Declining?

The truth is we still don’t know precisely why average IQ is going down. There are four solid hypotheses:

Parent stress. There is a well-studied link between maternal stress in pregnancy and lower child brain development. COVID-19 health and economic hardships have led to increased stress during pregnancy and for parents of young children. This likely had a negative impact on fetuses and newborns’ brains.

Parents spend more time online. According to the Pew Research Center, three in four parents have been online more frequently since the pandemic began, with nearly one-third of adults reporting they are now online “almost constantly.” This may have negative implications for child development.

Greater social isolation. Another likely factor is the increased social isolation of families and babies during the pandemic. This has been linked to negative cognitive and health outcomes.

Face mask wearing. In 1975, child psychologist Edward Tronick ran the famous “still face” experiment. When moms become expressionless, babies become more fussy. Some even start crying. Could new parents wearing masks have a similar effect on babies? Tronick and a colleague reran the experiment during the pandemic and found this did NOT affect babies’ neurodevelopment. Other scientists are still examining this question though.

Out of those four, parent stress is hypothesized to play a large role.

What Can We Do About It?

The good news is that intelligence is not fixed. Decades of published research have shown that IQ can increase over a lifetime. For instance, large IQ gains have been found in autistic children, when exposed to early intensive behavioral interventions. The magic word is early.

Baby brains are wired to learn. But they depend on critical human interactions during the first years of life to develop. This is a double-edged sword. Brain development accelerates through nurturing relationships. Neglect or abuse, by contrast, hinders growth.

Congress is evaluating policies that could positively affect the development of young children’s brains, starting with paid parental leave for working parents. A three-month paid maternity leave is linked to greater infant brain development. Anything that alleviates family poverty also positively impacts child brain development. Besides child tax credits, child care and preschool funding could also help. Access to quality child care is linked to decreased parental stress. The impact of child care on children’s brains is more nuanced, and depends on quality. In Norway, quality child care led to cognitive gains.

Beyond policies, responsive parenting practices are essential. We need to put devices down, and minimize digital distractions. The American Academy of Pediatrics recently called for greater focus on relational health. Employers can also play a supportive role. According to a McKinsey study, nearly half of companies have increased support for parenting employees since 2020. Relationship-centered preschools can also help increase IQ. Intergenerational approaches, such as a “Caring Corps” of one million grand-adults, could also be part of the solution.

The survival of our human species depends on us becoming smarter and more connected, not dumber and more isolated. It is time to counter the negative effects of the past two years on IQ and build our babies’ brains toward a brighter future.