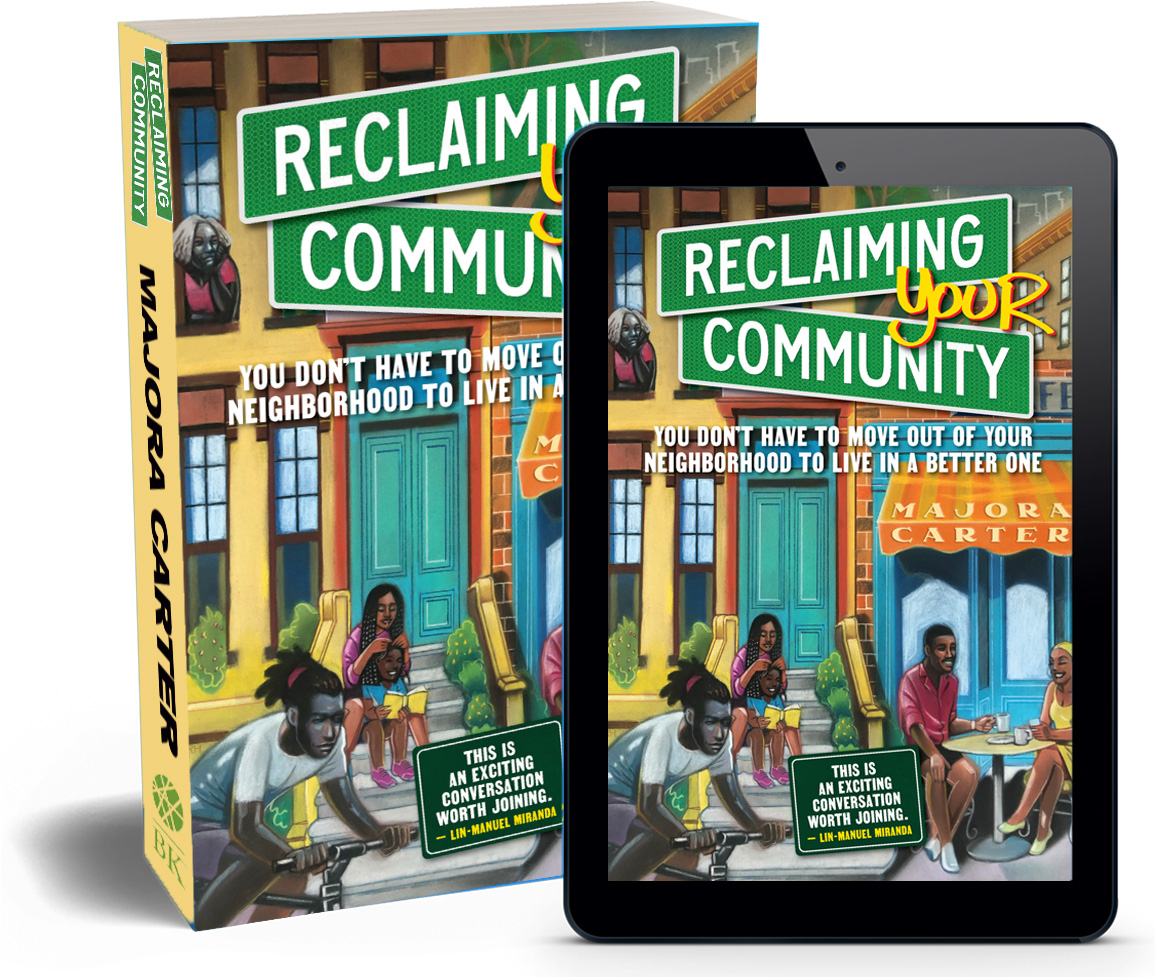

Gentrification is a subject that has launched a million listserv arguments. It often starts with complaints from longtime residents of color, devolves into rationalizations from white homebuyers and spirals into mistrust and outright hostility. Sometimes, gentrification seems inevitable, like continental drift or climate change, but activist, business owner and MacArthur fellow Majora Carter gets at the underlying issues like no one else.

(NY: Berrett-Koehler Publishers) 216pp.

“[Gentrification] starts when people in low-status communities believe that there is no value there,” she writes. “It happens when we tell ourselves that there is no value in our own communities and act accordingly.” Meanwhile, “An entire industry banks, literally, on the current inhabitants in those communities not recognizing the value.”

How do these insights apply to early learning issues in America? Consider the book’s subtitle. There are many reasons why families with young children move into or away from a neighborhood, but the availability of affordable, reliable early child care education often comes near the top of the list, along with safe, delightful playgrounds where families can gather. And who takes these items off the wish list and into reality? The solution doesn’t start with real estate developers. It starts with neighbors.

👉 Read our interview with Majora Carter

The long and short of it is this: building wealth within communities is good for babies.

Carter’s justifiably angry but ultimately hopeful book calls on all of us—gentrifiers and gentrified alike—to support policies and projects that support quality of life within low-status communities. The key to quality of life is wealth creation, and the key to wealth creation is real estate.

Her modest proposal:

“What if we made investments in the future wealth-generating capacity of low-status community members? This includes projects such as housing and business development that address aspirations for their lives, complete with lifestyle infrastructure such as nice bars, cafes and restaurants, as well as homeownership and local business development support for people who desire them.”

She draws some hope from a clear-eyed recollection of the past, including the history of relatives “taken up by chain gangs” in Georgia. They were walking through town, minding their own business, when they were arrested for “vagrancy” and then forced to “work off their fines” in quarries owned by local white men. Such outright racist and economic violence isn’t acceptable anymore, but the legal machinations deployed to extract wealth and labor from people of color is not merely an artifact of history.

👉 Our Child Care Facilities Are in Crisis, But There Are Solutions

The housing market is confusing. Mortgage rates. Credit ratings. Points. Taxes. Maybe it’s intentionally confusing. Carter believes that demystifying the mumbo-jumbo will enable residents to participate in the market rather than allowing themselves to get fleeced by predatory speculators; she remains furious at the fate of the house she grew up in. Local business development also figures into the equation, and her experience launching and operating the Boogie Down Grind is revealing in this regard. While many residents appreciate having an independent café in the South Bronx, others accuse her of perpetuating… you guessed it, gentrification. To these critics, Carter has a ready retort: coffee is the Blackest beverage on earth.

Beyond real estate savvy, Carter offers encouragement and wisdom for anyone seeking to improve the neighborhood. You don’t always have to agree with everyone at the community board meeting, but you have to be able to have a conversation. If you happen to come up with ideas, you should expect negativity—even from your own peers. “It is very disturbing at the time it happens,” she writes, “but I promise you, it becomes less and less so as you just keep doing the work.”

As someone who has spent his entire career working at and with nonprofit organizations, I found Carter’s dismissal of the sector hard to take, mostly because her critiques are undeniable. There is too much bureaucracy. Too much money goes to organizations led by people who look like (or went to college with) foundation program officers. At the same time, while she draws helpful lessons from the corporate world—especially the idea of talent retention—she may put too much faith in business, which, after all, is also mired in racism and exploitation.

Whether you interact with your community as a resident or business owner, through a nonprofit mission or a business agenda, Reclaiming Your Community will enlighten you, provoke you and challenge you to do better.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.