Just as Early Learning Nation showcases the ways families, researchers and grassroots nonprofits and organizations are building an early learning nation—one community at a time—our Community Cultivators series highlights how innovators across all sectors build and sustain global communities from the ground up. We hope the series inspires your own early childhood work.

In the 1970s, New York Times delivery trucks didn’t go to neighborhoods like Majora Carter’s. She used to accompany her father on weekly expeditions to track down the Sunday paper, and the first section she went for was always the magazine—not for the crossword but for the listings of million-dollar houses. “I was already attracted to a sense of home and place,” she reflects. “And as a kid I recognized our community was missing out on the ways that those things can be so life giving.”

Today, Carter is building life-giving places around the country, with a particular focus on low-status communities—a term she prefers to poor or low-income. Her new book Reclaiming Your Community describes a journey from South Bronx during the neighborhood’s most difficult era, through a successful but sometimes controversial nonprofit career, up to and including the formation of the for-profit venture, Majora Carter Group, with its ambitious mission: low-status community members experiencing a great community that meets their needs as well as their aspirations while they are ever more successful in it. Though laced with personal anecdotes, it’s less a memoir than a manifesto about unleashing community potential.

👉 Book Review: Majora Carter’s Community Manifesto Starts with Real Estate

She wrote the book because, while the community-wealth-building tools it describes have been in place since the formation of this country, they aren’t nearly well known enough. She marvels, “Nobody, and I mean nobody, is looking at those neighborhoods from the perspective of local people who need a little bit of extra help in order to be agents of change for themselves.”

Ilana Preuss, Founder & CEO, Recast City LLC, says, “Our low-status communities are filled with people launching and growing businesses, amazing storefronts to be filled and endless opportunities to build wealth. The question is: What is each community or neighborhood going to do about it? Reclaiming Your Community is how we get there.”

The best way to read the book is in the company of neighbors, whether or not you agree on issues like gentrification and economic development. “I hope it gives people an excuse to talk more with each other,” she says.

Majora Carter’s Top Recommendations for Reclaiming Community:

♦ Hold on to what you’ve got, part I: Property. Reclaiming Your Community poignantly recounts how Carter’s family sold the house she grew up in, only to see it triple in value. “My family personally lost about half a million dollars’ worth of wealth,” she laments. “We all need to identify and seize opportunities for wealth creation through real estate and business development.”

Home ownership and family stability go hand in hand. A Harvard University study authored last year by Don Layton (the former CEO of Freddie Mac) states, “Homeownership is regarded as causing an improvement in the quality of life of a typical family. It is the most common method for such a family to build wealth…. Homeownership is validly seen as a source of family stability.” For some, this argument runs counter to the demand for affordable housing, but Carter dismisses such objections: “We’re conditioned to think, ‘Oh, let’s just build affordable housing for more poor people because that’s basically all we’re ever going to be.’ And it’s true if we make it true, but why does it have to be the only truth?”

♦ Hold on to what you’ve got, part II: People. Carter’s book asks, “What if we designed low-status communities to encourage the talent born and raised there to remain, similar to the way companies try to retain their talent?” She admits that the phrase “gentrifying in place” hasn’t always gone over so well, but her experience in South Bronx and beyond confirms her belief that neighborhoods already have the brains and resources needed to nourish residents. “For communities, it means we’ve got this, everything we really need. We really do,” Carter explains. Nurturing talent starts early. She reflects on how her first grade teacher spotted her abilities: “Ms. Transport was probably the first person who told me outright that my creativity was something that I should just accept and share, which was really beautiful.”

👉 Listen to Carter on the Meditative Story podcast: ”You deserve to take your flowers”

♦ Dare to think differently. Carter is one of those people who refuse to accept reality the way she’s been told it exists. “When somebody tells me things have to be one way,” she says, “I’m going to think about other ways of doing it, and I’m going to ask why.” As a loner in her formative years, she says, she spent a lot of time observing. “It was just like, ‘Well, why not this?’ she recalls. The instinct didn’t necessarily endear to the philanthropic community. On one hand, after establishing Sustainable South Bronx in 2001, she won numerous awards, including a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “genius” fellowship. On the other, some funders and philanthropists didn’t appreciate her direct style. In her words, “I was just like, ‘I am not their girl,’ and so there’s no reason for me not to just speak my truth.”

♦ Learn from business (and not from nonprofits). Carter remains disillusioned with what she calls the nonprofit industrial complex. “It has been inflicting unnecessary collateral damage on our communities for decades,” she maintains, “entrenched in a sad cycle of diminishing returns despite ever-increasing spending. The culture addresses symptoms without offering, let alone implementing, a cure.”

Rather than collaborating, nonprofits act like they’re in competition with each other, and the philanthropic sector doesn’t really respect the work being done on the ground, and as a result a “plantation mentality” predominates. Her prescription: “Philanthropy should be the risk capital. Instead of letting predatory speculators buy our property, there needs to be patient capital to allow those communities to flourish.” Her shift from running a nonprofit to running a business reflects a belief that the latter is the lever for real change.

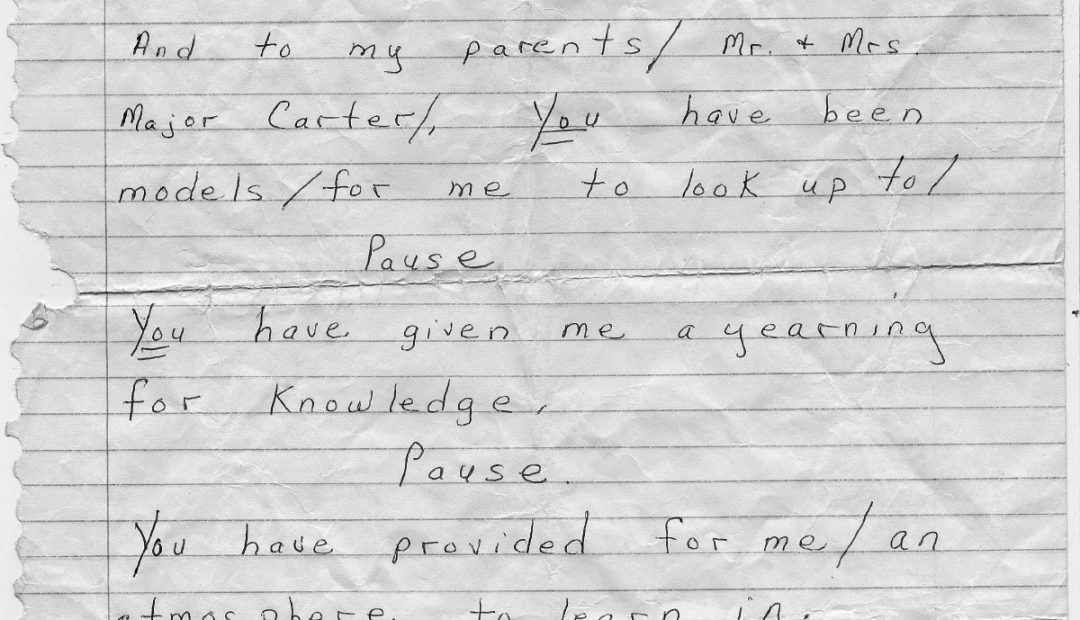

♦ Increase density and diversity. Carter has always been a builder. As a child, she took private creative writing lessons with a friend of the family. The only story she remembers from that era featured a runt whale named Willie. The other whales bully him, but then Willie and his parents build a kind of underwater playground—“a nice place for everybody to hang out and be happy together,” she recalls.

The qualities that support an underwater ecosystem can do the same for an urban neighborhood. Dense, diverse communities foster dynamic relationships full of promise and possibility. The goal, she says, is a “circular economy,” where the same dollar will circulate up to 14 times within the community, rather than being siphoned off by a chain store. The Majora Carter Group pushes for greater housing density allowances for new development, including space for early education.

Carter took an unconventional path to the real estate business, and while she admits her lack of formal training led to mistakes along the way, the fact that she’s doing it proves it can be done. “I hope others see what I’m doing,” she says, “and try their hand at being the developers of their own communities.”

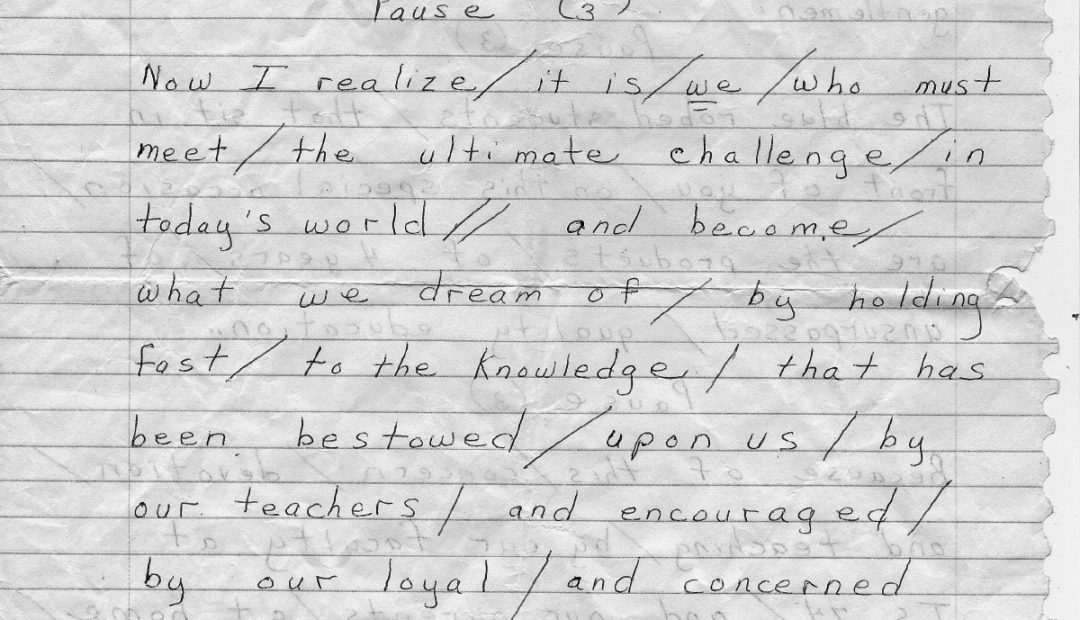

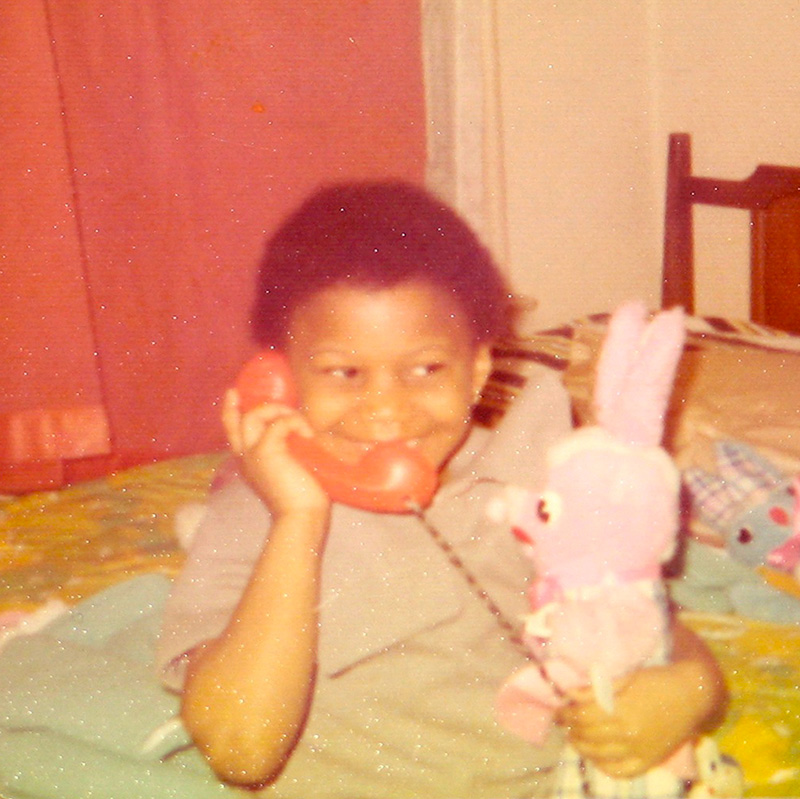

Pieces of young Majora’s life and accomplishments:

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.