Elliot’s Provocations unpacks current events in the early learning world and explores how we can chart a path to a future where all children can flourish. Regarding the title, if you’re not steeped in early childhood education (ECE) lingo, a “provocation” is the field’s term—taken from the Reggio-Emilia philosophy of early education—for offering someone the opportunity to engage with an idea.

We hope this monthly column does that: provocations are certainly not answers, but we hope Elliot’s Provocations helps you pause and consider concepts in a different way.

Federal child care funding is starting to feel a bit like Lucy and the football — and we’re all Charlie Brown. Not only is the House-passed Build Back Better Act dead, but any action on a narrower package centered around child care and climate change is unlikely to occur until the spring. In addition to contending with the war in Ukraine and government funding bills, the Senate will now shift attention to the historic Supreme Court nomination of Kentaji Brown Jackson.

The problem is, child care can’t wait. The sector continues to crumble by the week. With any federal funding cavalry delayed, states need to step up. In this column, I’m going to talk about three things: the active system-wide failure we are witnessing; the exceptionally weak state child care funding levels; and options for states to take action.

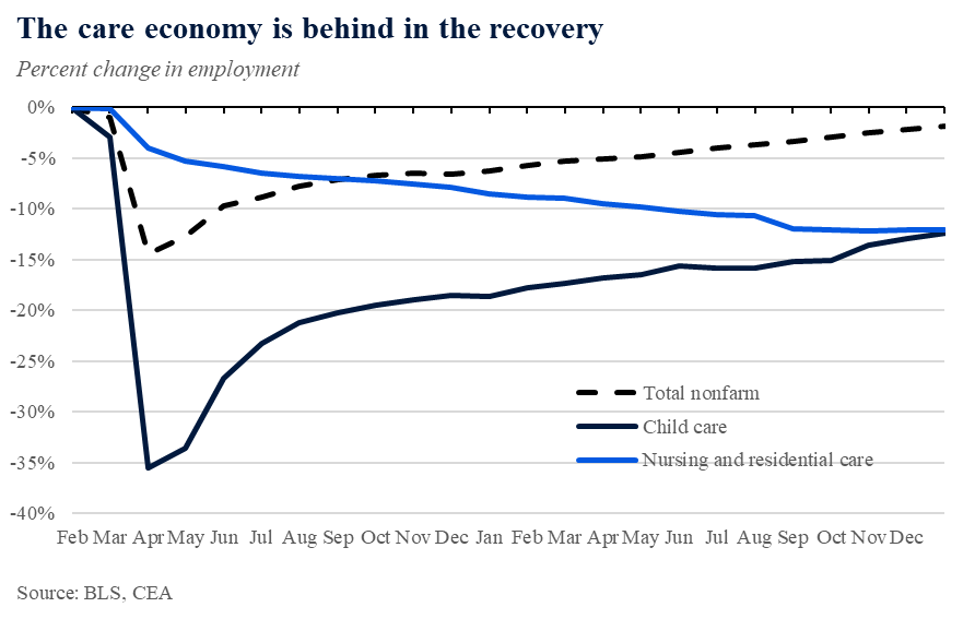

First, it’s worth reiterating just how dire the child care situation is. Per January’s job report, the child care sector remains 12% below its pre-pandemic staffing levels, a loss of well over 100,000 jobs (the only sector doing as badly is nursing homes).

What’s worse, the sector is showing no sign of real recovery, and has no credible path towards one. The pace of regaining jobs is glacial; between November 2021 and January 2022, only 13,000 child care jobs were added. The reasons why are no mystery, of course. As has been pointed out over and over and over again, child care programs cannot offer competitive compensation in this new era where retail and fast food behemoths have increased their base package, and workers finally have options. The child care system was incredibly fragile before COVID. Now it is broken. The story is as simple as it is tragic: a fragile system broke.

The consequences are equally as obvious: closures, reduced capacity and massive employee turnover — all of which is terrible for families, providers and most of all, children.

Let’s do a quick around-the-horn of local news over the past month, often the warning flare about realities on the ground. The sheer breadth of local news reports on the child care crisis is breathtaking: the struggle is real in every state, no matter its size, political leaning or urban-rural makeup. A cross-section:

“15 child-care centers in Collier have closed their doors for a loss of 712 child-care slots since the start of the pandemic in March 2020.

…Precious Cargo Academy at 5200 Crayton Road, which operated for 20 years at Naples United Church of Christ, closed permanently last September because of staffing and financial challenges. The parents of 66 children had to find alternative placement for their youngsters.

The most recent closing in Naples occurred Feb. 1 when Child’s Path-Moorings notified parents the center was closing temporarily until more teachers can be hired.”

“Tarren Hunter is one of dozens of parents heartbroken to see [X-Pressions Learning Center] close.

“I was kind of devastated,” she said.

“This is the third daycare that’s closing on us because of COVID and the pandemic. It’s definitely hard for them to keep up the staff here. My kids love it here, though. It’s like a family here.”

Owner Anthony Vaughters says they’re shutting down due to finances and COVID.

“COVID has really impacted our business financially, emotionally,” he said.”

Before Angie Riedemann’s family moved to Madison at the end of January, the post-doctoral researcher contacted 40 local child care facilities to provide her 16-month-old infant support while she and her husband reported to their full-time jobs.

Not one center had an opening, she said.

“I wish I were exaggerating, but I counted them all up,” Riedemann said. “I knew it was difficult to find child care in Madison, but I wasn’t sure the extent of the problem … I went into panic mode.”

You get the idea; feel free to spend a few minutes on Google News for your own state. It won’t take long, trust me.

Something must be done.

I’ve been noting recently that businesses are freeloaders when it comes to child care, in that they put zero dedicated money into a system they benefit deeply from. States may not be freeloaders, but they’re at the penny-ante table.

Nationally, as of 2019, the federal government put approximately $22 billion annually into early care and education, while states combined for $12 billion. As a comparison, states combine to spend around $640 billion on K-12 education each year. $640B vs. $12B. $640B is… more.

Let’s look at two very different states to get a sense of how that plays out: my home state of Virginia, and Utah.

In 2020, the nonprofit Virginia Early Childhood Foundation produced a Children’s Budget report that looked at all the different funding streams going into early childhood (defined broadly: child care and state pre-K as well as home visiting, special education services, etc.). They found that the state spends $247 million on early childhood. Since most of that is targeted towards lower-income children, even using that as the denominator as opposed to all young children, the report still concluded “per capita state spending on [low-income children aged zero to four] is about $1,500.” (The per capita spending on all young children, you can imagine, would be three figures.)

Now, Virginia has a population of 8.5 million residents, and has had both Republican and Democratic control over the past two decades. The Commonwealth spends over $6.5 billion on public education in state funds alone (excluding local contributions), with a state-only per-pupil expenditure of $5,500 that is actually quite low. So I say this with all hometown love: $247 million a year for early childhood is pathetic.

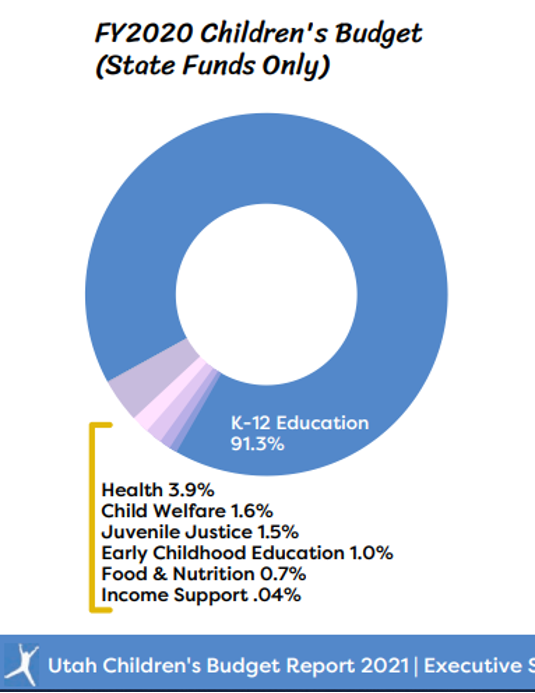

The story is much the same in Utah, where the advocacy group Voices for Utah’s Children has found that a mere 1% of state funds spent on children go to early childhood education, as opposed to a whopping 91%(!!) to K-12 education:

None of this is to pick on any given state; you can again feel free to take a couple minutes and go find a very similar story for yours. Why this massive discrepancy? All the threads about a history of sexism and denigration of the early years connect here, of course. But there is also a major lack of forcing function.

All 50 state constitutions contain an unconditional right to free public education. That right currently exists in no state constitutions when it comes to early care & education. So, states have generally been happy to let the federal government carry the water when it comes to child care funding (meager as it is), and for most of 2021 it looked like Congress would in fact let states off the hook.

The best laid plans of mice and men often run into Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema and the Senate Republican caucus.

So what can states do? First, let’s be crystal clear about what they should not do — raise child:adult ratios to unsafe levels like what Iowa is currently planning. We cannot allow children’s well-being to suffer as a result of our miserliness.

The primary lever for states to pull is permanent funding for staff compensation (reducing parent fees is important as well, but it doesn’t help much on its own to make closed doors cheaper to enter). Permanent is critical here: the problem with the American Rescue Plan Act money and other one-off payments is that they expire. With one-off payments, you can improve a facility, make payroll in a bad month, or pay off organizational debt. You can’t really increase pay and benefits and then two years later wrench them away. The conversation starts and ends with permanent compensation increases.

Washington, D.C., despite not even being an official state, is showing how it can be done. As The Washington Post reported in early February:

“Thousands of day-care workers in Washington will get personal checks from the D.C. government for at least $10,000, after the D.C. Council voted unanimously Tuesday to redirect tax dollars from the city’s richest residents to child-care workers, who legislators say they believe are underpaid.

The council raised taxes on the city’s highest earners last year, and the members voted at that time to set aside $53 million in the first year of that tax to somehow raise the pay of day-care workers, saying that their work was vital to the city’s families but not sufficiently compensated by their current salaries.

…the council indicated that it will set up a program to do so in future years, probably by subsidizing part of workers’ paychecks from their employers so that child-care workers will be paid on a scale comparable to public elementary school teachers.”

That’s it, right there. Finding a new source of revenue to produce major, sustainable compensation increases. $10,000 a year amounts to a 25%+ raise for many D.C. early educators. While a state’s policy details may vary (there are many ways to route funding), the overarching model has now been laid out.

Other states are trying, to be sure. New York has a proposal on the table for a $5 billion investment towards universal child care, financed through a business payroll tax. Colorado leaders put admirable energy and political capital into passing a nicotine and cigarette tax that will raise close to $200 million a year for their early childhood education system. New Mexico has been at the forefront of changing the way states can pay providers to more closely reflect the true cost for operating sustainability.

This is the level of imagination and investment required. Half-measures simply will not serve to build up a sector that has now structurally failed. It may even be time to start seriously considering constitutional amendments to enshrine a right to voluntary child care. The good news is that alongside conversations about big dedicated revenue streams, we can talk about how child care pays for itself and the consequences of inaction is self-inflicted economic pain.

States may have hoped that the child care ball wouldn’t end up in their court, but here it is. For the sake of their constituents, their economies, and their futures, it’s time for states to get fully in the game.