For adults who’ve spent much of the past two years watching PowerPoint presentations while attending Zoom meetings, the idea of doing so every day for two weeks might not sound like a massive opportunity. For the 5-year-olds in the University of Washington’s I-LABS online reading camp, it was a chance to connect with friends every day and play some cool games. Bonus points: Discovering that “d” makes that “dah” sound, “a” makes that “ah” sound, “d” is “dah” again and when you put them all together, holy moly, you’ve just read “dad.” A word!

For the I-LABS researchers, the project shows that a well-structured, evidence-based reading instruction program can make a measurable difference in teaching children key reading skills, even if delivered fully online and just for two weeks.

“We were surprised at how successful it was,” says Dr. Yael Weiss-Zruya, a research scientist at I-LABS and first author of the study, “Can an Online Reading Camp Teach 5-Year-Old-Children to Read?” published in Frontiers of Human Neuroscience. The study details a virtual reading program in which 83 5-year-old children worked remotely with teachers on key reading skills. By the end of the camp, the children who participated had improved significantly in all measures compared with children who did not take part in the virtual camp.

In 2019, I-LABS researchers, including study co-author Jason Yeatman, had set up a two-week summer reading program at the university to teach early literacy skills to pre-kindergarten students. Weiss-Zruya inherited the program just before the pandemic started and the researchers quickly began to consider how it might be adapted to an online version.

“The team put a lot of thinking into how to keep the kids engaged,” she says. “With the in-person program, the hands-on activities kept it interesting for the children. But trying to keep them engaged remotely, we knew, would require more prompts from the teachers, more visuals. We needed to be more creative.”

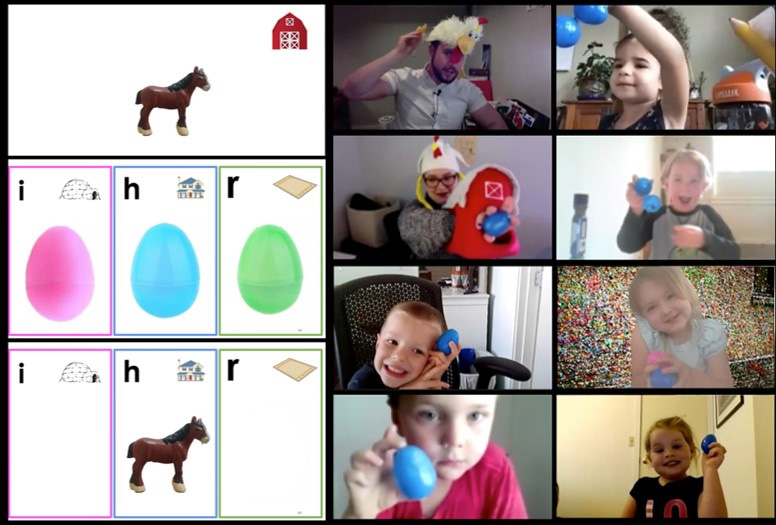

Weiss-Zruya adds, “We created themes for the day—one day it was a farm theme, another day it was space—and the teachers got dressed up accordingly.”

Including, yes, a teacher wearing a chicken on his head. Anything for science.

An essential element to the reading program was the ability of the kids to interact with each other and the teacher. Because social interaction is such an important part of learning for children in this age group, the researchers made certain that participants could get to know each other in as close to in-person connections as possible.

“We mixed the groups every day, so each kid eventually got to be in a group with all the kids during the two weeks of the camp,” Weiss-Zruya says. “We didn’t turn off the mics, but we put in a lot of effort in explaining Zoom manners; like, you need to stay in the Zoom window in the video box, and if you need to say something, wait for your turn or raise your hand, let the teacher know. But we did encourage them to interact with each other.

“So many parents want to sign their kids up for different apps that will just automatically teach them to read. They’ll put the kids in front of the computer or iPad and forget about them and hope the kids will learn to read. That’s very different from how we know to help kids learn. I’m not saying anything against these programs, but we can’t trust them solely to teach children to read. It’s important that kids have both the peer learning environment and the direct interaction among the kids and teachers, and this is a bit more challenging in an online setting.”

To facilitate that interaction and discussion in the group sessions, the research team mailed a kit to each child containing such items as worksheets, books, crayons, Playdoh, DUPLOs (LEGO building block sets) and a set of child-sized headphones. For families without internet connection or a computer that could be devoted to the daily time needed for participation, the project provided iPads and internet connection.

The in-person reading camp involved playing with cards and toys, so the team had to sort how to translate those activities into PowerPoint presentations compelling enough to engage a bunch of 5-year-olds—a tough crowd by any standard. Waving a colored plastic egg or other prompts to “vote” on the right answer and other playful activities did the trick.

The program focused on phonology—distinguishing different sounds—letter knowledge, and mapping letters to sounds. Each day’s program ended with a story, underscoring the idea that the goal of reading is to comprehend what’s written.

Throughout the COVID-19 epidemic, children throughout the world have had limited (or no) access to consistent, structured teaching. From early in the pandemic, researchers and early learning specialists sounded the alarm over the probability of significant losses in reading and math achievement, and warned that school closures would increase the disparity between students from lower- and higher-income families. Indeed, a recent policy analysis by Stanford University researchers confirmed these pessimistic predictions and showed that in more than 100 U.S. school districts throughout the U.S., students fell about 30 percent behind in reading fluency scores in fall 2020. Students in lower-achieving schools fell even farther behind. A 2021 study of 5.5 million students in grades 3 – 8 by the Northwest Evaluation Association’s (NWEA) Center for School and Student Progress showed similar losses in reading and math achievement.

As U.S. schools shut down physically in March 2020, teachers and school systems quickly went into action to try the best they could to deliver online learning. Studies comparing online and face-to-face instruction in pre-pandemic K-12 education have shown that virtual programs can be as effective as face-to-face instruction—sometimes even more effective. But most online programs have served older children, grade 6 and up, and many have been heavily weighted to families of mid-to-high socioeconomic status.

Success in online learning during the pandemic depended in large part on students’ access to the necessary technology, the amount of caregiver support from home, the level of student engagement and other factors.

Because reading is a foundational skill for participation in the modern world, educators and researchers are keenly aware of the urgency in finding solutions to early literacy learning. While online learning seems like an attractive possibility, scant research existed to see if that was even possible. The I-LABS online reading program goes a long way to answering that question.

Dr. Patricia Kuhl, the study’s faculty author and I-LABS codirector says that the reading camp shows that an online program designed to promote learning socially can work “phenomenally well.” The camp can be used all over the world by children anywhere, she says.

The limitation of the present model is that it involved a group of six children, with breakout sessions of three children to one teacher; I-LABS was set up to do no more than four groups of six children a month. Weiss-Zurya says the next step is to see if more children can be added without reducing the program’s effectiveness. The project will also begin to work on semantics and the structure of language, as well as deploying powerful Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to see if the online reading camp program induces the same brain changes observed in the children when the program was being delivered in person.

But first things first. Thanks to I-LABS’ virtual reading camp, 83 5-year-olds are now on their way to becoming people who read. Today, 83 children. Tomorrow? With appropriate resources, maybe the world.

Resources

University of Washington Institute for Learning & Brain Science (I-LABS) is an interdisciplinary center dedicated to discovering the fundamental principles of human learning, with a special emphasis on early learning and brain development.

“Can an Online Reading Camp Teach 5-Year-Old-Children to Read?” Published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, the study was funded by the Bezos Family Foundation, the Overdeck Family Foundation and the Petunia Charitable Fund. Co-authors were Yael Weiss-Zruya, Jason D. Yeatman, Suzanne Ender, Liesbeth Gijbels, Halley Loop, Julia C. Misrahi, Bo Y. Woo and Patricia K. Kuhl.

Changing Patterns of Growth in Oral Reading Fluency During the COVID-19 Pandemic, by Benjamin W. Domingue, Heather J. Hough, David Lang and Jason D. Yeatman (2021) Stanford, CA, policy analysis for California Education, Stanford University.

Learning During COVID-19: Reading and Math Achievement in the 2020-21 School Year, by Karen Lewis, Megan Kuhfeld, Eric Ruzek and Andrew McEachin (2021), and Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA), a research-based not-for-profit organization that supports students and educators globally by creating assessment solutions that precisely measure growth and proficiency.

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.