Not everyone who comes to America is pursuing the American Dream. Some are in flight from life-threatening crises. Layered on top of the ongoing influx of immigrants at the southern border, the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan and the Russian invasion in Ukraine are causing new waves of immigrants and families to seek safety and security in America.

I spoke to experts from Kids in Need of Defense (KIND) and the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) to learn more about how educators and community partners can welcome and support the youngest new Americans. KIND offers legal support and social services to unaccompanied minors. MPI strives to come up with realistic policy solutions to manage migration, immigration and integration

Here are seven insights for teaching and serving immigrant children.

1. Immigrants live everywhere. Historically, we think of Texas, California, Florida and New York as immigrant hubs. While these states have the largest shares of immigrants, the picture is far more spread out, says Essey Workie, director of the Human Services Initiative at MPI. “We’re seeing more and more immigrants in rural communities,” she notes, “whether it’s because of the price of housing or because of agricultural work opportunities.” (Learn more.)

2. The journey from Latin America is especially traumatic. Children come to the U.S. from all over the world, often escaping violence and persecution. In the case of new arrivals from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras (which account for most unaccompanied children and families arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border), gangs and the threat of sexual and gender-based violence have forced them to flee for their lives. “Children flee trauma,” says Kena Mena, Social Services supervisor at KIND. “Then they experience trauma again and again on their journey here and throughout their experience.” According Workie, the trauma they experienced may not be fully expressed until children begin to feel safe with a parent or sponsor.

3. “Trauma doesn’t define migrant children,” declares Argelia Tlatelpa Perez, Senior Social Services coordinator at KIND. Teaching respect and inclusivity with a culturally responsive lens can help them to cope with trauma and to get ready for school. Perez recommends being especially patient with these children as they acculturate to the U.S. They may not reveal their feelings right away, but careful listening can bring about trusting relationships. Young children are remarkably resilient, says Mena, but only with the help of caring adults.

4. Know who is in your community. As a teacher, you may know the names of the children in your classroom, but do you know where they’re from? Workie encourages educators to know “the languages they speak at home, the cultural practices they have, the faith groups they affiliate with,” adding that while it isn’t appropriate to ask about religion at the time of enrollment, these discoveries can be made through family engagement. “That’s a great way to honor the students’ background and heritage,” she says.

5. Get familiar with available resources. As Workie describes it, the fate of children processed by the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) is anything but straightforward: “When a child leaves federal custody and goes to live with a parent or other sponsor in the community, ORR doesn’t have legal custody anymore. The parent or sponsor is responsible for the child’s well-being, but they are often unauthorized themselves and have limited access to benefits and services. And there often isn’t intensive case management to help them navigate this very complex maze.” Educators may not have the knowledge to serve as advocates, but helpful resources include:

- MPI’s Strengthening Services for Unaccompanied Children in U.S. Communities (see sidebar)

- The Child Welfare Information Gateway’s list of Organizations Providing Information on Immigration, Refugee Resettlement, and Child Welfare

- The Kaiser Family Foundation’s report on Title 42 and Its Impact on Migrant Families

• Legal services are crucial for a child’s case and for links to other services, but federally funded legal services are limited. [Read more]

6. Immigration enforcement often exacerbates the stress. Imagine you’re living in a new country, trying to learn a new language and make new friends, but at the same time, law enforcement officials are targeting your family and people who look like you. According to a fact sheet from the American Immigration Council, “Immigration enforcement actions—and the ever-present threat of enforcement action—have significant physical, emotional, developmental and economic repercussions for millions of children across the country.” Educators in some communities have decided not to voluntarily share immigration status and other confidential information about students and their families with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (this agency’s warrants are not legal but rather administrative).

7. Mental health supports matter for these kids. Immigrant children often feel like they have nowhere to go for emotional relief and no one to talk to. Feelings of loneliness, sadness and worthlessness are common. As Workie explains, one-on-one counseling with a psychologist is rarely an option—especially when Spanish-speaking therapists are in such short supply. She mentions peer-support groups and sports or arts activities as vital for managing mental health and stress levels. “Play matters,” says KIND’s Mena. Her organization provides puppets, song, sensory toys and stickers for children in shelters run by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

A Book for Immigrant Children

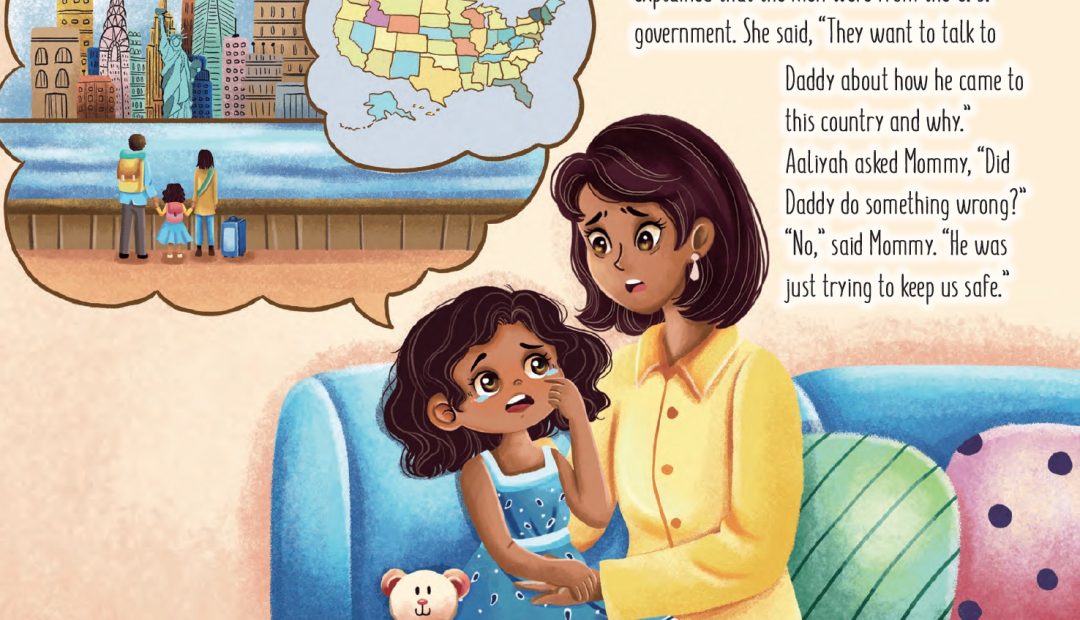

Aaliyah The Brave by Rekha Sharma-Crawford helps readers understand the impact immigration enforcement can have on children and what emotions children may feel in the aftermath. When immigration officials come to Aaliyah’s home and take her father, she and her family find themselves coping with a variety of emotions. As they prepare themselves for the legal proceedings in immigration court, Aaliyah realizes how brave she is, and the family realizes how important communication about what is happening helps to empower her. Learn more.

Check out some sample pages:

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.