An unfortunate fact about the health care and child development information physicians try to cover during well-child checkups is that it can sometimes go in one ear and out the other, says researcher Dr. Stephanie M. Reich. These office visits are usually stressful for parents as they wrangle their baby, sometimes with siblings, and try to absorb what the doctor is saying while the child gets weighed, gets a shot or just tries to escape from the exam table.

But the information is critical. A large body of research shows that the more parents know about typical child development and effective parenting, the better they interact with their children and provide them with stimulating environments. Parents with a better understanding of what to expect as their babies develop feel less stressed, more effective, and better about themselves and their infants.

By contrast, parents who don’t know what to expect are often impatient and intolerant of the baby’s actions, misinterpreting normal child development as bratty or malicious behavior, increasing the possibility that the child could be mistreated. Parental impatience and intolerance also directly affect infant attachment, which can lead to harsh, inconsistent, disengaged parenting and the cycle of issues that can arise from that.

Reich, a professor in the School of Education at the University of California-Irvine, researches the factors that influence parenting behavior and how those influences affect children’s development. While working on her doctorate at Vanderbilt University, she and a fellow in developmental pediatrics, Dr. Kim Worley, along with their advisor, Len Bickman, began looking at how the process of delivering parental education might be improved.

In 1994, the American Academy of Pediatrics created the Bright Futures Guidelines—well-structured, evidence-based parent-education material intended to be delivered across 31 age-based visits. The guidance has been updated and revised over the years, most recently this year, to help health care professionals spread the word on child health and behavior to parents and caregivers. The information is there but getting it into the hands of parents is rarely as simple as it ought to be.

“Theoretically, well-child checkups should be a good time to educate parents about injury prevention, typical development and optimal parenting practice,” Reich says. “But there’s a lot of evidence that if physicians can spend any time covering parent education it tends to be a minute or less, and maybe covering three topics. When parents are interviewed later, even if the physician covered a lot of material, they don’t remember much of it.”

Sometimes the doctor’s office will give parents handouts based on the Bright Futures Guidelines, but often their literacy level is too high for many families. As the two researchers discussed alternative methods of spreading the word, they hit upon the idea of embedding the information in baby books—not books about babies a lá Drs. Spock and Brazelton—but books for babies. The books are written at a first-grade level, have pictures to supplement the text and will be read multiple times.

“If you’ve had a child, you know that you read the same books over and over and over,” Reich says. “We thought we could capitalize on this repetition.”

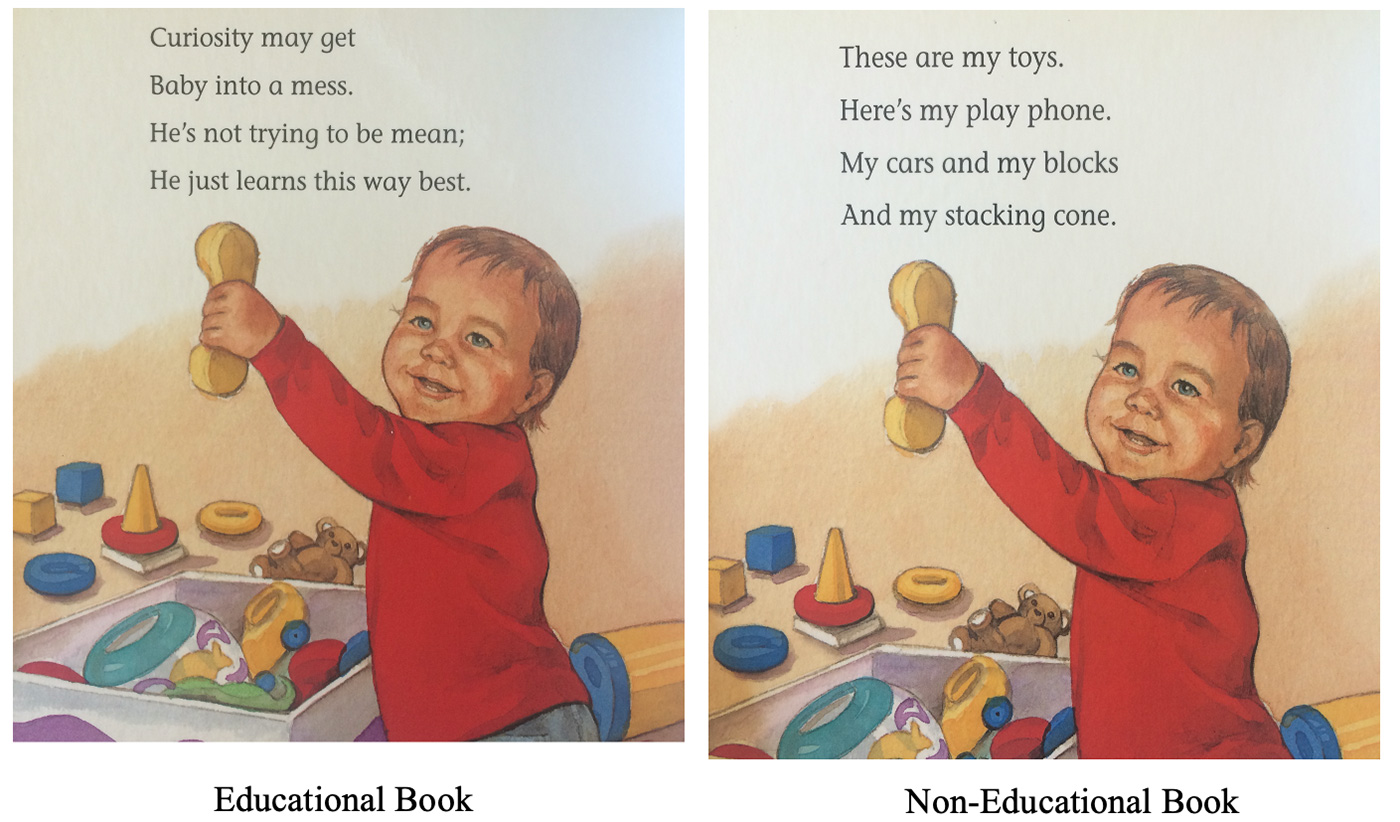

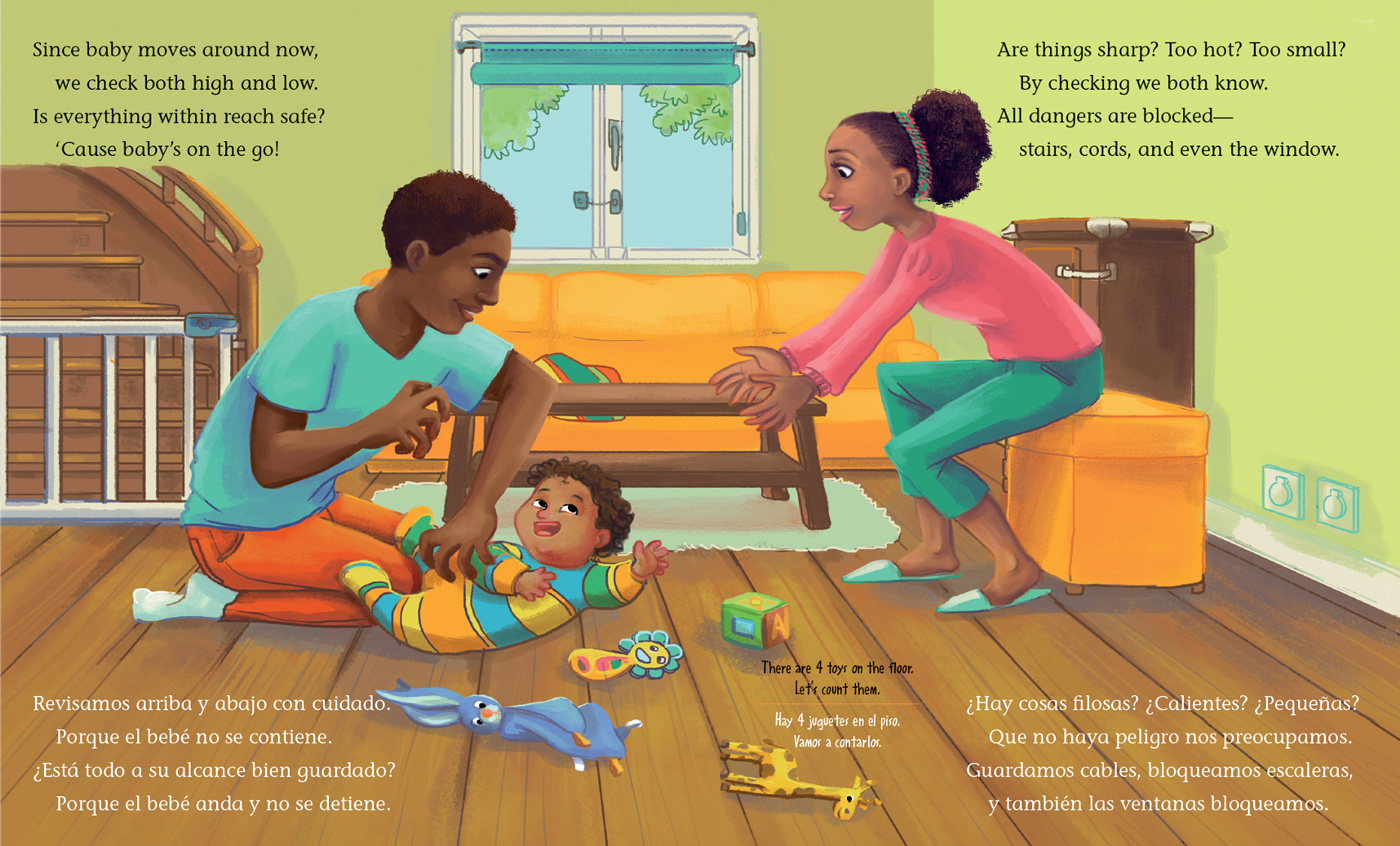

For the initial Baby Books Project (there are two so far), Reich and her colleagues at Vanderbilt created a three-group randomized study to compare the impact of educational books with noneducational books or no books at all. The researchers created a series of professionally illustrated board books targeted to different stages in babies’ development, with content addressing why babies might be behaving in a particular way, which parents might interpret as misbehavior, and how hitting won’t correct the behavior. The text also discussed tantrums and the value of praise, distraction and redirection when dealing with baby’s meltdown. The noneducational books feature the same illustrations, but without the informational approach. Both sets of books contained images of ethnically diverse families and were written in short, catchy, rhyming stanzas.

The books featured messages on the inside of each cover about self-care for the moms with such topics as managing stress, eating well and what to do when they’re feeling overwhelmed. The first project followed 145 low-income, first-time, predominately African American mothers in the southern US, from their last trimester of pregnancy until their child was 18 months old. In Baby Books 1, all books were delivered in person during home-based data-collecting visits.

Baby Books 2, which Reich developed in partnership with Dr. Natasha Cabrera at the University of Maryland, replicates and expands on the first project by including first-time mothers and fathers, and targeting co-parenting. Families in the study are low- to moderate income in Washington, D.C. and Southern California, and are racially and ethnically mixed. The books were written in both English and Spanish and the project was divided into four parts: families receiving books for mothers, books for fathers, books for both mothers and fathers, and noneducational books.

Thanks to a grant from the National Institutes of Health, the second study, which had been derailed by COVID-19 because researchers could no longer go to subjects’ homes, was expanded to 46 months and the books were mailed to families rather than requiring in-person visits. The results are now being evaluated but early analysis indicates many of the same positive results as Baby Books 1.

Based on assessments at all stages of data collection for Baby Books 1, mothers in the group receiving educational books increased their knowledge of child development and positive parenting practices, showed reduced support for spanking, increased efficacy and read more often to their children.

Children of the mothers receiving the educational books had fewer preventable injuries compared with the other groups. An analysis of medical chart audits of doctor office, emergency room visits and hospitalizations found that the impact of preventing injuries such as burns, cuts, falls and dropping showed that the educational book resulted in an overall estimated cost savings of $14,194 compared to the non-educational book group and $128,954 compared to the no-book group.

“The economist who did the analysis tried to calibrate the cost considering that when a child is injured, they have to be taken to the doctor and the parent has to miss work. There are costs around preventable injuries beyond the injury itself, and if the injury is significant, that can change the family’s quality of life.

“As we were hoping, the families did change some of their safety practices in the home,” Reich says. “If the action was putting away choke hazards or removing plastic bags or keeping dangerous things away from the kids, the moms changed those behaviors—mainly the practices that didn’t cost them money. If it meant installing smoke detectors or using baby gates, we didn’t see any changes because our families were very low income.”

The women’s feelings of stress and depression were measured at regular intervals throughout the project. At baseline—the women’s third trimester of pregnancy—the scores for depression hovered just below the criteria of clinical depression for all the women. Though those symptoms gradually decreased for all in the children’s first 18 months, the intervention group became less depressed faster than women in the comparison and control groups.

Where the needle didn’t move, Reich says, was the mothers’ practices around food. The first books included a lot of information about nutrition and breastfeeding.

“We had zero impact on any of that. The parents did better on demonstrating their knowledge, but they didn’t change their feeding practices whatsoever. That’s a common finding—food practices in families are a really hard thing to change. So, in the second baby books, we took all of that out because it was space in the books that wasn’t having an impact on behavior, so we moved in other information.

“We’ll see how that goes,” she says. “My hope is that with each study we’ll figure out what pieces are really amenable to change, and which aren’t and then really target those that are will have utility.”

Though the books are not available for distribution, the researchers hope that they eventually might be able to partner with a publisher to make the books widely available, for instance in Reach Out & Read programs in pediatric clinics or offered during Women, Infants and Children clinic visits. The books could also be made available through public libraries, preschools or bookstores.

“Maybe it could become like the TOMS shoes model where if someone buys a book, the publisher gives a free book away,” Reich says. “It’s such a low-cost, easy-to-disseminate, easy-to-implement intervention, I would love to see it expand.”

RESOURCES

For information on the longitudinal Baby Books 2 project, visit the program website.

Bright Futures is a national health promotion and prevention initiative, led by the American Academy of Pediatrics and supported, in part, by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). The Bright Futures Guidelines provide theory-based and evidence-driven guidance for all preventive care screenings and well-child visits.

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.