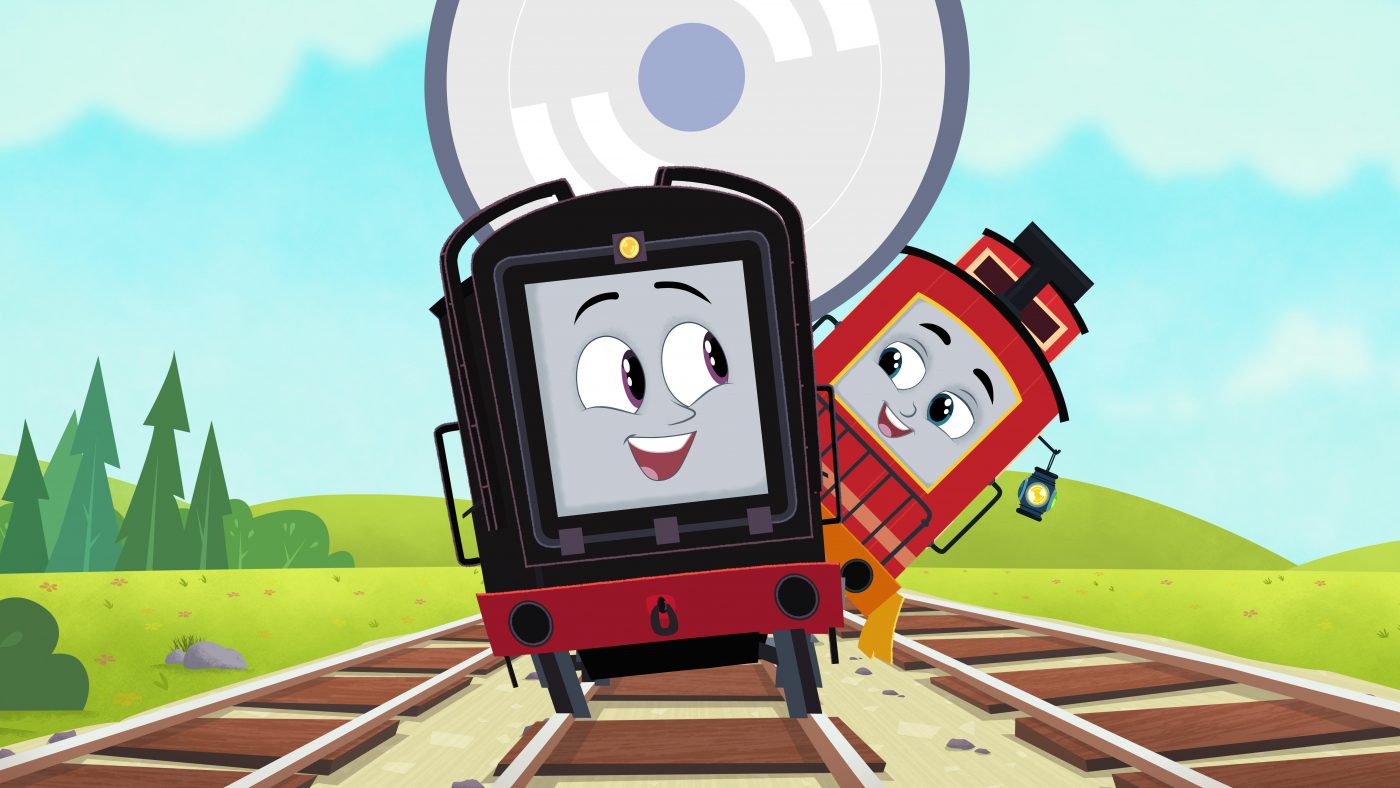

When parents and kids tuned into “Thomas and Friends” this September, they discovered a new character: Bruno the Brake Car. They also found a positive representation of autism on the British children’s TV show.

Though Bruno just premiered this fall, it took years to get him on track. Mattel began developing the character in early 2020 and turned to consulting partners to develop his personality traits and behaviors. Psychologists, autistic writers and the Autistic Self Advocacy Network all collaborated with Mattel to help bring Bruno to life.

“We asked our autistic collaborators about misconceptions and stereotypes, as well as their wishes for how they would want to see autism depicted,” Monica Dennis, senior director of preschool content at Mattel told Early Learning Nation in an email. “That conversation guided specific choices about Bruno’s characteristics and our approach to storytelling.”

Daniel Share-Strom, an autistic writer and advocate, led Bruno’s character description and wrote Bruno with other autistic writers, including female autistic writers. Dennis felt it was important to include female voices since autism is often diagnosed in men and therefore men are represented more than women. In the U.S. version of the show, autistic actor Chuck Smith voices Bruno, while Elliot Garcia won the role in UK.

“Underrepresented kids, including neurodiverse kids, should see themselves celebrated in stories and play,” Dennis said. “‘Thomas & Friends’ has a strong affinity in the autistic community, so including an autistic character is an organic validation of our fans.”

Parents may have heard the term “neurodivergent” used more often to refer to kids with autism, but it’s not a medical term. It was coined by the Australian sociologist and autism advocate Judy Singer in the late 90s as a way to acknowledge differences in cognition and behavior. The term has been applied to those who exist on the autism spectrum, as well as those with developmental disabilities like ADHD, according to Harvard Medical School.

Autism itself is a developmental disability caused by neurological differences. The disability exists on a spectrum, so the communication, socializing and behavioral issues that people with autism face may vary from person to person. Some people with autism can be more sensitive to stimuli like loud noises or light and might deal with the sensory overload through physical actions like jumping up and down.

“What we like to say is when you’ve got one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism, and everyone displays their personal characteristics differently,” said Dr. Paula Pompa-Craven, a licensed clinical psychologist who specializes in the assessment and diagnosis of people with autism and other developmental disabilities. Pompa-Craven is also chief clinical officer of Easterseals Southern California (ESSC) Autism Therapy Services, which served as one of Mattel’s consultants on the show. She added that some individuals with autism may have intellectual disabilities or are nonverbal, but they communicate in different ways.

“The one thing with autism is if you look at a person, they do not look like they have a developmental disability,” Pompa-Craven said. “Some of the other developmental disabilities are defined. So you might look at someone with Down syndrome and notice this person has Down syndrome. With autism, you may pass someone on the street and they look exactly like the rest of their peers.”

Positive representation of different groups is particularly crucial for preschool children, said Polly Conway, senior TV editor at Common Sense Media.

“The more that they see, the more that they’ll be able to understand,” she said. “Then there’s also scaffolding and ways that parents and teachers can say, ‘Have you met a person like this? Is there someone in your class like this that you know?’ So, I think seeing the character on TV can just sort of be the beginning of a learning process.”

Several children’s shows have introduced characters with autism including “Hero Elementary,” “Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood,” “Dinosaur Train” and “Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum.” A decade ago an autistic character named Carl joined PBS’ “Arthur” and Julia joined “Sesame Street” in 2017.

“We believe it is important for all kids to see themselves in our content,” Sara DeWitt, senior vice president of PBS KIDS corresponded. “To that end, research shows that when children see themselves represented in television shows, the experience boosts self-esteem and self-worth. This is critical for children in traditionally underrepresented communities, including kids with varying abilities.”

👉 Watch this PBS Newshour segment on Bruno the Brake Car.

The trend of autistic characters on television mirrors representation that’s happening in real life: 1 in 44 children have been identified with autism spectrum disorder according to a 2018 estimate from the Centers for Disease Control. That incidence rate has shot up from where it stood two decades earlier when the CDC estimated that about 1 in 150 children had autism.

Still, Conway argues that this reflects a broader trend of including different kinds of people in children’s TV shows, not just autistic people.

“I haven’t seen a huge rash of new characters who have autism, but I have seen more,” she said. “I think that correlates to what we’re seeing in the world today. The more we learn about people and what’s going on with them, the more we’re going to be able to represent them.”

While it’s not possible to represent every child on the autism spectrum, Bruno exhibits certain behaviors that some people with autism express. The Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) advised Mattel on how Bruno’s disability would affect him in daily life, how he would react to sensory overload and what facial expressions he would make, said Zoe Gross director of advocacy at ASAN. The advocacy group has consulted on other children’s programming, including advising the development of “Sesame Street’s” autistic character, Julia. However, ASAN ended their partnership with Sesame Street in 2019 after the show ran PSA’s featuring Autism Speaks’ “Screen for Autism” initiative, which ASAN said further stigmatized autistic people.

How certain traits of autism would manifest themselves in a character that isn’t human emerged as an interesting challenge for both ASAN and Mattel, Gross said. Mattel knew from the start that Bruno would be a brake car and approached ASAN with the idea that he would flap the railings on the side of his car, rather than hands.

Bruno has other gestures that don’t have a real-life comparison in autistic people, such as his lantern that flashes red, yellow or green to indicate that he’s excited or cautious. The lantern mimics communication badges that first emerged in autistic conferences and are used to demonstrate the person’s communication preferences, Gross said. A green badge means the person wants people to approach them while red means the person doesn’t want to interact with anyone or perhaps only a few people.

“It’s hard because you don’t want to show every kind of characteristic of an individual that you’ve ever come in contact with,” Pompa-Craven said. “We really wanted to look at maybe some of those things that were more persistent within the autism community.”

One of those persistent qualities that Mattel and consultants included in Bruno’s character was a lack of direct eye contact, according to Pompa-Craven. When Bruno’s eye contact is fleeting or moves to the side, that could show his comfort level. He also self-soothes when he hears loud noises by putting on headphones. But Bruno isn’t alone in dealing with hurdles like sensory overload. The program also shows his friends helping him out.

“The other characters would remind him, ‘Hey, Bruno, you seem like you’re getting a little agitated. Why don’t you see him on those headphones?’” Pompa-Craven said. That supportive community teaches children that it’s okay to accept people as they are, she added.

At the same time, Bruno expresses his own agency and helps out the rest of the cast as well. Consultants wanted to create a positive role model for autistic children. They show Bruno excelling at problem solving, examining maps and closely following schedules. In one storyline, the other trains run off schedule and Bruno helps them find a new route to correct their time.

“That was really important as well, that we showed the positive characteristics and the gifts that he added to the team,” Pompa-Craven said.

Another way to avoid harmful stereotypes with an autistic character is to continue including them in various episodes, whether they’re part of the main storyline or the B plot, Conway said. She noted that Sesame Street has now incorporated Julia as part of the team of muppets that go on adventures together.

“It’s always important to steer away from tokenism,” Conway said. “Really keeping a character in the mix is a great way to write them and avoid showing them appearing as just a token basically…giving them a story that they have to tell or opinions that they have regardless of their, you know, communication abilities.”

For those in the autistic community, the portrayal of an autistic character that was developed with the input of autistic people appears to hold some promise.

“No single character can encapsulate autism, just as no single female character can encapsulate ‘womanhood’ and no single Black character can encapsulate ‘Blackness,’” said Kristen Harrison, a professor of communication and media at the University of Michigan who is also autistic herself. “Part of the goal is to get more characters out there so people in a given demographic can be represented onscreen with the same complexity and diversity that exists among them in real life. But, of course, that all has to start with individual portrayals like this one.”

Leigh Giangreco

Leigh Giangreco is a journalist who has chronicled everything from the catastrophic failure of the Pentagon’s most expensive fighter jet program to why Joe Biden is on Tinder. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Politico, Washington City Paper, Citylab, Washingtonian, Eater Chicago, and more.