Every time Emmy Thibodeaux drops off or picks up her two-year-old son at child care, there’s a situation being managed, a crisis averted. “I always walk in on the director filling in for someone, or the director in the kitchen shouting, ‘I’m over here.’” Sometimes the afternoon teacher is the same as the teacher who was there in the morning, and sometimes not. “There’s always a lot of juggling,” she says.

This is the life of a child care director before and since the pandemic.

In addition to her personal interest as a mom in the ballet (or circus) of child care, Thibodeaux is also observing the juggling and managing as Early Childhood Network Supervisor with Lafayette Ready Start (LRS). It’s a program of the Louisiana Department of Education dedicated to expanding access to and improving the quality of early care in the parish. This includes public preschool, nonpublic schools of early childhood development, Head Start, Early Head Start or Type III Early Learning Centers (defined by the state as those authorized to accept public funding through the Child Care Assistance Program).

For Thibodeaux, “There’s the heart of this work, and there’s the business. I love to see a child care center that has both. That’s where the magic happens.”

LRS has been doing this work since 2012, and the program was making steady improvements until the pandemic hit. “It was like taking 10 backward steps,” Thibodeaux says. “Sites started closing classrooms because they didn’t have teachers.”

In order to get a handle on what was happening in its network, LRS commissioned Advancing Communities for Equity (ACE) to conduct a survey and virtual focus groups. Directors of and teachers in 51 early childhood centers across the parish expressed their views on business challenges, supports and the future. Many of the responses corresponded with Thibodeaux’s account, with a director of a three-center business reporting, “We had to reduce enrollment because we did not have teachers. Before the pandemic, we were full. In the last 16 months, we have been unable to enroll new children.”

“Two years into this pandemic,” said another director. “We are starting to see burnout. Teachers don’t want to work as much as they had. They could go down the road and make more at McDonalds.”

👉 Read the Lafayette Ready Start 2022 Early Childhood Workforce Study

ACE’s Emmy O’Dwyer (the second Emmy in this story) knows these issues inside and out. She started her education career as a middle school teacher, but she started an early childhood center shortly after Hurricane Katrina, upon discovering her newborn had a disability. “I just couldn’t believe how underfunded and decentralized everything was,” she says. “I couldn’t believe the work that these teachers were doing and how little I was able to pay them.”

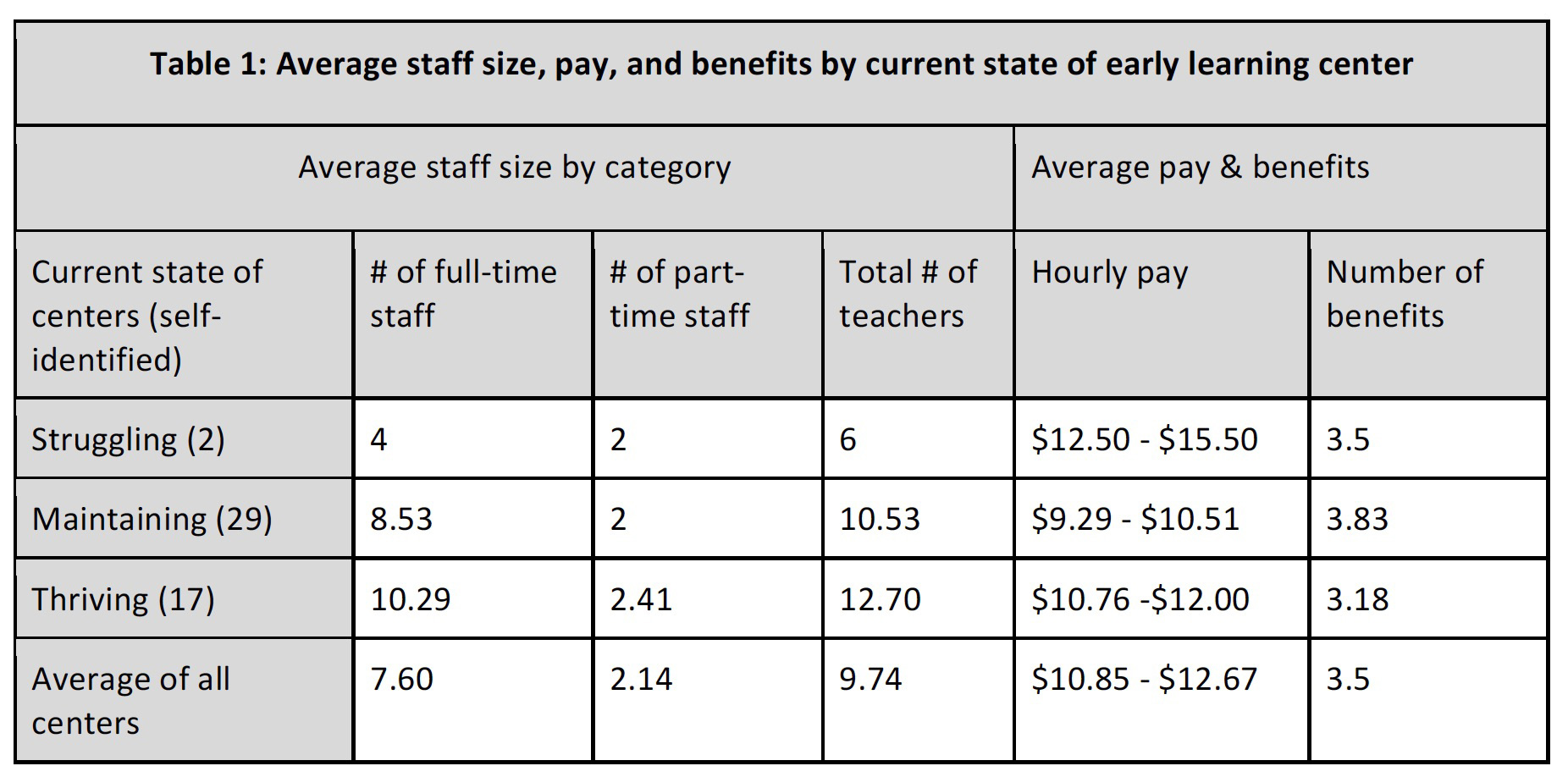

For her LRS-commissioned research into Lafayette early learning centers, O’Dwyer set out to identify meaningful differences between centers whose directors characterized their situation as thriving, maintaining and struggling. She considered size, pay, benefits, instructional leadership and organizational culture. While pay is an inevitable factor, with directors saying they were competing with other employers (as well as the option of accessing unemployment benefits), staff size emerged as the most notable difference between thriving and maintaining centers. According to O’Dwyer, “Thriving centers had the largest staffs and indicated fewer pandemic-related staffing challenges.”

Pay and benefits matter, of course (and will continue to matter until early educators are compensated like schoolteachers), but O’Dwyer found that money counts less to the educators than how they are treated. As long as the community continues to regard their work as babysitting, they will feel undervalued—a factor that determines whether they remain in the field or defect to retail or other, better-paying sectors. “It would be nice to get paid a little more,” one teacher acknowledged, “or get benefits like teachers. I would just like some respect, that what we do is important.”

These findings resonated with Thibodeaux’s sense of the mood of early educators during this fragile moment. “We need to celebrate and recognize the workforce. They’re performing at a very high level despite the lack of materials and lack of supports.”

Awards and recognition help them feel respected “As a mom,” Thibodeaux reflects, “I drop off, I pick up, and I’m just rushing in and out.” Like a lot of parents, she finds herself forgetting to acknowledge the many ways that early educators make her career possible.

“We need to honor this important work,” contends O’Dwyer. “And centers need to get their business operations in order. They need to use the ‘Iron Triangle’ of early childhood finance (full enrollment, full fee collection and revenues that cover per-child cost), and they need to be supported on the front end to set up their business the right way.”

👉 Louise Stoney, The Iron Triangle: A Simple Formula for Financial Policy in ECE Programs

For O’Dwyer, organizational culture is a critical factor that determines whether a child care center will flourish. She touts early childhood fellowship programs (such as the Louisiana Early Leaders Academy) as an efficient and pragmatic way to help directors to focus on their own leadership, learning and growth. “Teachers might turn over every two years,” she says. “In Louisiana, someone is a director for seven to nine years. And so that’s a worthwhile investment.”

In response to the survey findings, LRS is studying high school pathways for students to earn a Child Development Associate credential upon graduation, a teacher mentor program for onboarding new educators and a deeper study into the feasibility of increased pay, expanded benefits, substitutes pools and other workforce strategies.

Thibodeaux describes LRS as a testing ground for pilot programs. “We’re the first to jump in,” she says, and “find out what works and what doesn’t in our community.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.