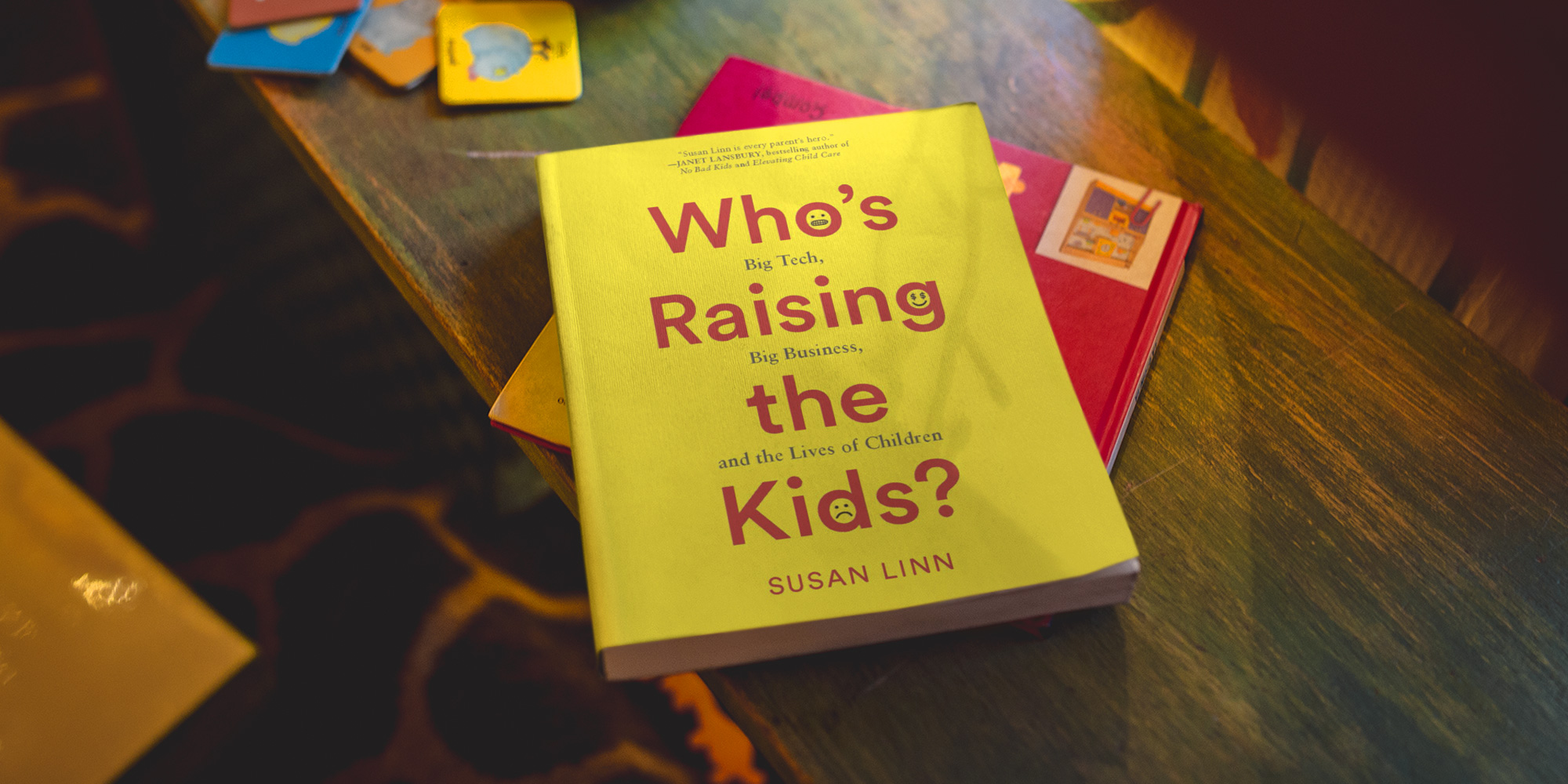

Susan Linn

Who’s Raising the Kids: Big Tech, Big Business, and the Lives of Our Children

The New Press, 316 Pages

When my kids were little, we had three rules for buying stuff.

- We don’t buy anything that’s advertised on Saturday morning TV, a rule I’d override for birthdays and Christmas. Otherwise, nope.

- If you pester or nag me in the store, we go to the car. If you persist, we go home. Game over. It took twice for each child to get the message.

- We don’t buy cereals with sugar as one of the first two ingredients. This sentenced my children to a life of Cheerios, Shredded Wheat and Wheat Chex—as they would tell anyone who’d listen.

And that was that.

But that was Before. Before an entire multi-billion-dollar industry developed for the explicit purpose of getting kids to pester and nag their parents to buy absolutely everything. Before an entire children’s media ecosystem grew up as a venue for advertising and marketing to kids more than for educating or entertaining them. Before digital technologies made it possible to swamp children in advertising more sophisticated, invasive, manipulative and devious than any of us could possibly have imagined. Before every parent trying to do the right thing became David trying to say no to a Goliath so pervasive and entrenched in every moment of their child’s life that it is rendered practically invisible.

In her excellent book, Who’s Raising the Kids: Big Tech, Big Business, and the Lives of Children, Dr. Susan Linn brings this insidious behemoth to the foreground and underscores it with bright red lines. She maps the current landscape of children’s marketing and advertising through deep research and the eyes of an insider who’s been involved for decades in children’s media. A ventriloquist and entertainer, Linn worked with Fred Rogers, first as a guest with her Audrey Duck puppet on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and later with his production company creating video programs. Linn, a psychologist and expert on creative play and the impact of commercial marketing on children, was founding director of Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood (now called Fairplay). She is a research associate at Boston Children’s Hospital and lecturer on psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. She is also a mother and grandmother and writes that her activism is as deeply rooted in that personal perspective as in her professional experience.

Since Linn began working in the late 1990s to stop corporations from targeting children, the situation has gone from bad to unbelievable—a progression launched in the 1980s with the deregulation of children’s television. It became legal then for companies to create programming whose sole purpose was selling children toys—and they took to it with gusto. Consider, for instance, the 1994 marketing conference in London called “Pester Power: How to Reach Kids,” or the 1998 marketing research study on “The Nag Factor,” written not to help parents cope with children’s nagging or reduce it responsibly, but to provide corporations more tools to support kids in becoming successful naggers.

Advertising Immersion

With the advent of smartphones and tablets, most children are in front of a screen whenever and wherever they go, despite growing evidence that excessive screen time is harmful to children’s—especially young children’s—health and development. They are inundated by ads in every game they play, every store they enter, every video they view. In-app purchases urge kids to buy cool new gear for their avatars and to upgrade, upgrade, upgrade, fomenting envy and shame for kids who can’t keep up, and turning every game session into a battle of wills with parents who may not be able to afford the constant financial demands or who simply resent the incessant pressure to pay up.

As Linn describes in her chapter, “Branded Learning,” school is no respite from this constant barrage. In their classrooms, “free” tablets are an opportunity for companies to instill lifetime brand loyalty, and clever teaching materials promote Disney properties or fossil fuel companies’ hype along with their lessons on nature. The list is endless; this chapter will blow your mind with the many and varied ways corporations insert themselves into the hearts and minds of our kids in educational settings.

Advertising sells values and attitudes right along with the products it hawks to children, and those values are often antithetical to healthy family relationships or even the old-fashioned idea of good citizenship, Linn writes. Children are constantly sold on the belief that competition is king and the things will make us happy, when research suggests that the opposite is true: More materialistic children are unhappier than their less acquisitive peers.

In the chapter, “Bias for Sale,” Linn shows how prejudice, bias, stereotyping, and social stigma are baked into many games, virtual worlds, social networks and even in the search engines we rely on throughout the day. A study in the journal ACM Queue from the Association of Computing Machinery showed that ads implying that someone had been arrested were more likely to appear in searches for “Black-sounding names,” such as “Latanya Sweeney.” While a search for “Kristin Lindquist” turned up neutral ads.

People believe Google searches turn up fair and unbiased information—statistically, younger users believe this more—when the fact is that racism is embedded in the algorithms and inflicts harm on children as well as adults. Imagine the effect on a child who googles her name and finds it associated with criminality. A watchdog group reported in 2020 that the tool Google uses to help companies decide what search terms they should link their ads to was linking the phrases “Black girls,” “Asian girls,” and “Latina girls” to pornographic search terms. It isn’t a stretch to imagine how hatefully these biases play out on children.

No Legal Obligation

In the current U.S. regulatory landscape, the tech companies that create and own these algorithms have no legal obligation to share how or why their search results are selected. These algorithms are written by humans whose biases influence their creations, Linn writes. These employees don’t work for institutions whose mission is to serve the public interest, but for tech companies whose primary goal is to maximize profits. “Just as Facebook isn’t a public square, Google isn’t a public library,” she writes.

Dr. Linn is not anti-technology—she just wants it to assume its proper place in our lives and the lives of our children. Her goal isn’t to make parents feel guilty about failing to cope perfectly with the tsunami of carefully targeted temptations every child encounters every day, but instead to help anyone who cares about children understand the “toxic, digitized, commercialized culture” so many children wake up to in every day.

This culture’s impact extends beyond individual well-being to the well-being of our larger society. The solution doesn’t rest in individual parents, she writes, but in working together to push back against the monetization of American childhood. Her “Resistance Parenting” chapter offers excellent suggestions for how to introduce tech to young children and how to manage their use of technology into their teen years. Most importantly, she emphasizes that this isn’t a battle that can be fought on an individual level but something we must embrace as a society. Powerful forces are invested in manipulating children for profit, but they are not all powerful. Parent groups, communities and fed-up friends have formed advocacy groups, undertaken educational campaigns and even, in the case of Minnesota’s Digital Well-Being Bill, gotten a state legislature to provide $1 million to promote resources, education and a leadership program to support young people’s balanced use of devices.

The situation isn’t hopeless, and no one is helpless, though it will take concerted effort to create the social change needed to put technology in its proper place.

Who’s Raising the Kids is the perfect place to start—a research-based primer in what’s at stake, who the players are and how we got to this place. It’s truly a must-read for anyone who cares about the future of America’s kids.

Resources

Fairplay: Childhood Beyond Brands In 2000, Susan Linn and her colleagues formed the nonprofit advocacy organization Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, which is now called Fairplay. Over the years, Fairplay has convinced some of the world’s largest corporations to change some of their most egregious marketing to children. Among other initiatives, Fairplay:

- Got Disney to stop marketing Baby Einstein videos as educational for babies

- Prevented Hasbro from releasing the Pussy Cat Dolls, based on a burlesque troupe, for 6- to 9-year-olds

- Convinced the NFL to shut down a fantasy football game targeted to kids

- Stopped Google from collecting and monetizing children’s personal information on YouTube Kids and forced the company to significantly limit the kinds of advertising allowed there

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.