The First 10 initiative of the Education Development Center (EDC) supports a network that will soon include more than 60 community partnerships in Maine, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Alabama, Massachusetts and Michigan. Some are First 10 School Hubs, which are anchored by a single elementary school; and some are First 10 Community Partnerships, which bring together multiple elementary schools and the early childhood programs in the community. The efforts nurture relationships between early childhood organizations, public schools and health and social service agencies.

In part I of this interview, David Jacobson, who designed and leads the initiative, discusses the tenets of the model and their context. Part II focuses on three examples.

Mark Swartz: How does the First 10 initiative approach early education?

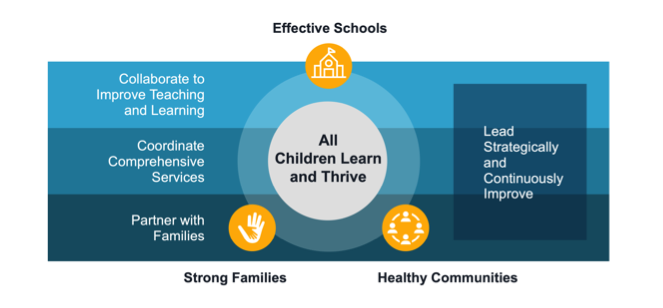

David Jacobson: First 10 begins with a commitment to educational and racial equity and the whole child. We summarize this in the expression All children learn and thrive. We convene partnerships that take joint action around three core strategies.

- The first is to collaborate to improve teaching and learning. A key component of this collaboration is to develop and implement a comprehensive plan for transition to kindergarten.

- The second strategy is to coordinate comprehensive services across schools, health care organizations and social service agencies.

- And the third is to deepen partnerships with families. This is about elevating family voice, conducting outreach to culturally specific groups and creating culturally responsive structures.

Swartz: How does First 10 compare to other cradle-to-career initiatives?

Jacobson: Whereas most of those initiatives create separate teams to work on kindergarten readiness and early-grades reading, First 10 partnerships come together around quality across the full early childhood to elementary school continuum, beginning with prenatal care and extending through elementary school.

Swartz: How did First 10 get started?

Jacobson: I had done technical assistance and applied research on this kind of work for years, and then the Heising-Simons Foundation funded a study that came out in 2019 called All Children Learn and Thrive: Building First 10 Schools in Communities. Since then, communities in six states have embraced the approach. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation provides support for the First 10 Network, which brings communities together to learn from each other through monthly webinars.

Swartz: Can you describe how a First 10 Hub or Community Partnership launches? Does First 10 show up and start organizing the stakeholders?

Jacobson: In some cases, we work with states to recruit interested communities, and then we support these communities as they convene a partnership, and develop and implement a First 10 plan. In other cases, the communities reach out to us directly. We begin by examining the work under way in each community and assessing assets and needs. We then develop a plan that draws on the practices of exemplar First 10 communities. Once a First 10 team has developed its plan, we divide into work groups to carry it out.

Swartz: Who carries out the projects in the communities? Is it First 10 staff or local participants?

Jacobson: The local participants carry out the projects with our support. We facilitate the First 10 teams as they design their strategies, and we provide practical tips based on our experience working in other communities.

Swartz: Along with all this alignment work, First 10 also catalyzes joint action, right?

Jacobson: Absolutely. For example, as I mentioned, all of our communities implement comprehensive transition to kindergarten plans, which is that connecting piece between pre-K or Head Start and kindergarten. In addition to improving orientation experiences for children and families, we bring Head Start, community-based pre-K, district pre-K and kindergarten teachers together regularly to compare standards, curricula and instructional approaches.

We work on social-emotional learning, early literacy and early math. Teachers exchange teaching strategies and motivate each other’s innovation and improvement. We also organize school-connected play and learns, in which young children and their caregivers engage in fun, developmentally appropriate activities. There’s reading, songs, arts and crafts for the children and adults to do together as well as learning opportunities for the caregivers.

And we connect these families to services. We also promote community-wide parenting campaigns, where all the organizations that touch the lives of children and families come together around a set of common messages. Through all of this we have a bigger impact.

Swartz: What is some recent research that informs your work?

- First 10 Schools and Communities are aligning prekindergarten and elementary school education and reworking curricula, assessments and instruction.

- First 10 School Hubs are providing influential supports to families and other caregivers of children ages 0–4 and then continuing those supports throughout elementary school.

Jacobson: For one, Advancing Racial Equity Through Neighborhood-Informed Early Childhood Policies, a 2021 study by the Diversity Data Kids project, which is housed at the Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University. The study finds that neighborhoods have a big impact on children’s outcomes and developmental risk, independent of family socioeconomic status.

The authors make a strong case for local coordination and alignment at the neighborhood and community levels. There are particular implications for neighborhoods that were hit hard during the pandemic.

Swartz: Can you provide some context about how this fits into federal and state policy—especially in terms of funding?

Jacobson: A significant step at the federal level is the Preschool Development Grant Birth through Five program for state and local system building. Alabama, Michigan, Maine and Rhode Island are all using these state system-building funds to support partnerships at the local level that bring together elementary schools and school districts with Head Start programs, community-based early childhood programs and health and social services. It’s important that states have their own pilot projects.

The U.S. Department of Education is funding full-service community schools grants, and those grants include a very significant early childhood component. The Council of Chief State School Officers and the Education Commission of the States both bring together states to work on early childhood—elementary school collaboration and the transition to kindergarten.

Swartz: And at the local level?

Jacobson: Children’s cabinets are an important policy-making structure. State-supported county collaborations like Great Start Collaboratives in Michigan foster communication among district officials, principals, early childhood leaders and families. We are finding that Children’s Cabinets and county collaboratives can work hand-in-hand with on-the-ground initiatives like First 10 that focus on implementing strategies in neighborhoods and communities. A little bit of magic happens when we bring this work to our districts and neighborhoods, and states and counties can play key roles in supporting these efforts.

Continue reading Part II here.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.