Just as Early Learning Nation showcases the ways families, researchers and grassroots nonprofits and organizations are building an early learning nation—one community at a time—our Community Cultivators series highlights how innovators across all sectors build and sustain global communities from the ground up. We hope the series inspires your own early childhood work.

Valerie June is a singer and songwriter with a unique and infectious sound, but she’s more than that. She’s a yogi, an entrepreneur and a former professional house cleaner. (Doing something for seven years makes you a professional, she notes.) And now she’s an author.

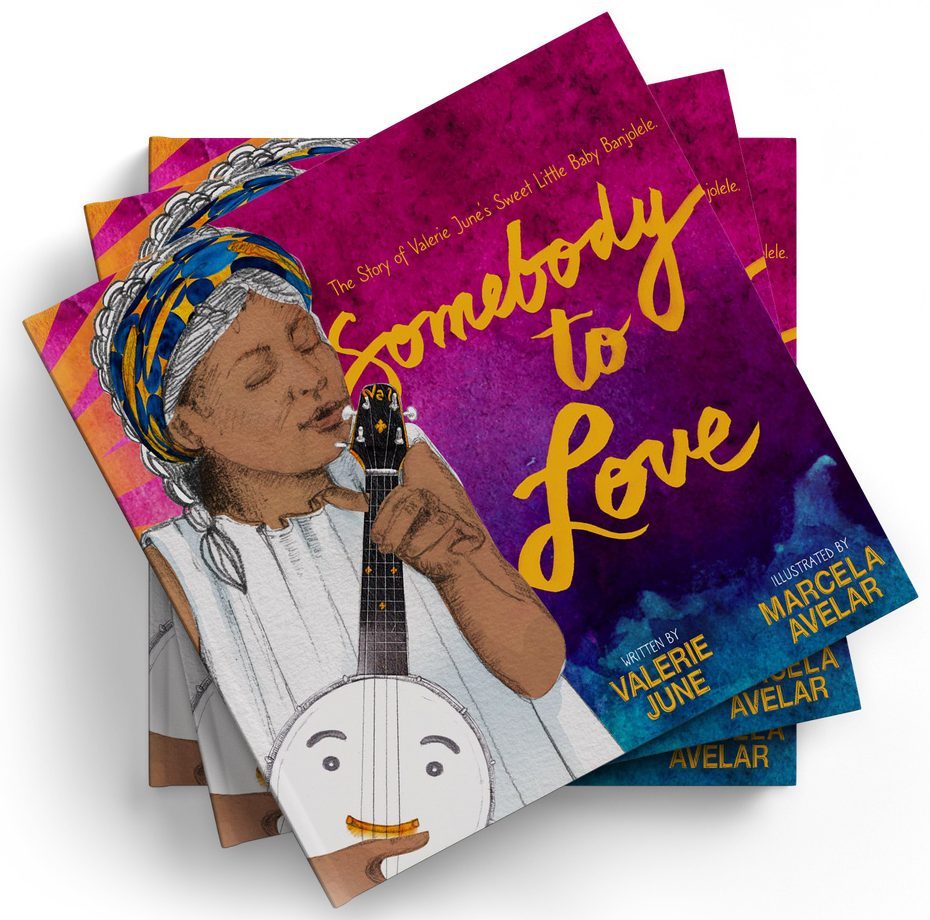

The main character of her children’s book is a toy instrument, a banjolele (half-banjo, half-ukulele) named Baby. With illustrations by Marcela Avelar, Somebody to Love came out this past November, but its journey began six years earlier. June was taking part in the Kennedy Center’s Turnaround Arts program, founded by Michelle Obama, which sends artists and creators into schools throughout the nation. Students loved her story about Baby, and Turnaround Art’s Kathy Fletcher encouraged her to turn it into a book. “When I heard Valerie tell the enchanting story,” Fletcher told me. “I knew it would be an immediate favorite as a children’s book. I’m so happy that this beautiful book, with its positive, inspiring message is out and reaching children everywhere.”

The main character of her children’s book is a toy instrument, a banjolele (half-banjo, half-ukulele) named Baby. With illustrations by Marcela Avelar, Somebody to Love came out this past November, but its journey began six years earlier. June was taking part in the Kennedy Center’s Turnaround Arts program, founded by Michelle Obama, which sends artists and creators into schools throughout the nation. Students loved her story about Baby, and Turnaround Art’s Kathy Fletcher encouraged her to turn it into a book. “When I heard Valerie tell the enchanting story,” Fletcher told me. “I knew it would be an immediate favorite as a children’s book. I’m so happy that this beautiful book, with its positive, inspiring message is out and reaching children everywhere.”

When not on tour, June lives in Humboldt, Tenn., and Early Learning Nation magazine caught up with her for a brief but intense call. Here’s what we learned.

1. Anything can be creative. Last month at South by Southwest, June and memoirist Nabil Ayers gave a talk together about creativity. Her message to people who don’t think they’re creative is: Think again. You may not play an instrument or write poetry, but any pursuit can take a creative form, if you think of it that way. “Maybe you like to design your nails,” she says, “Or maybe you love to cook. It’s about the tone of things. It’s the way you do it.”

As a struggling musician, she worked as a house cleaner, and there were lots of times during those seven years that she hated the drudgery and counted the minutes until she could get out of there. “There were other days,” she notes, “when I saw myself as a domestic artist, and I was ready to go make other people’s homes beautiful and to have it be a sanctuary for them when they came back.” June and Ayers urged their SXSW audience to think of creativity as an antidote to overwork, media oversaturation and all the toxic elements of our society. “There is a revolutionary power in creativity,” she asserts, “and in the communities that it builds.”

2. At first, all it takes is 10 minutes a day. Although banjolele is one of the easier instruments to learn, June confesses that, unlike singing, not every part of music comes naturally to her. “I never doubted my ability to belt out a song,” she says, recalling the time she sang “This Land Is Your Land” in Mr. Wallace’s fourth-grade class. “Instruments, that was the hard part. And keeping time,” she adds, thinking back on the girls on the playground who mastered elaborate hand-clapping games. “I couldn’t keep the rhythm at all. It was very embarrassing. So I decided, Why not become a musician for a living? I like a challenge.”

Learning anything new can be frustrating, but her rule is to start with 10 minutes a day. “I get mad at the instrument and sometimes have to walk away,” she says. “But it’s still there waiting for me the next day.” With practice, the 10 minutes stretches out to a half-hour and then an hour or more. And before you know it, people like Bob Dylan and Norah Jones start noticing. Her 2021 album The Moon and Stars: Prescriptions for Dreamers, Rolling Stone magazine declared, “ultimately feels like a record about perseverance, survival and acceptance, about turning one’s gaze from scars to nighttime stars.”

3. Different is good. As a singer, June always knew she didn’t sound like other singers. Her tone is a bit scratchy and sometimes nasal and won’t remind anyone of her 80s idols, Whitney Houston and Tracy Chapman. The word idiosyncratic comes up a lot. “Her voice is at once grounded and cosmic, earthy yet divine,” says NPR’s Oliver Wang. June admits, “I always used to ask myself, Why am I doing this? And the answer was always, I’m doing it for me. I’m doing it because I love it, for my joy.” She’s grateful for the growing audience that does connect to her music. For those who don’t—it’s simple: “Not everything’s for everybody.”

4. Yoga means unity. The word yoga, June explains, comes from a Sanskrit word meaning to join or unite. “The ultimate goal is union,” she says. “Which is the point of anything that gets you out of the ego and the self and all the things not helping people to grow and build community.”

Her forthcoming publication, Light Beams: A Workbook for Being Your Bada** Self, concerns, in her words, manifesting dreams. It’s not just about working on yourself, she says, referring to a theme common to many wellness titles. Whether readers are connecting to nature or to their communities, the aim is overcoming the forces constantly trying to divide us, based on race, class and status. “I don’t think everybody has to be volunteering for everything at every meeting of their neighborhood association,” she says. “You could be a hermit and create a harmonious world by aspiring to unity.”

5. Kindness takes a little extra effort. The years she spent cleaning houses, among other memories, help June to try a little harder when people are less than pleasant. “Think about the neighbor that you just don’t get along with,” she says, “or the person at the coffee shop who’s grumpy all the time who clearly doesn’t like you. How do you build a community and keep love in action with them?” That person’s stress is not yours to take on, she counsels, but there’s a lot of darkness in the world, and you just have to remember a lot of us are worried and frightened and don’t always remember to smile.

There’s something good waiting at the other side of fear. According to June, the lesson of her book is this: “There’s a little voice inside you that says, I’m scared and I’m terrified, but I really, really, really see myself one day able to make it through a song.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.