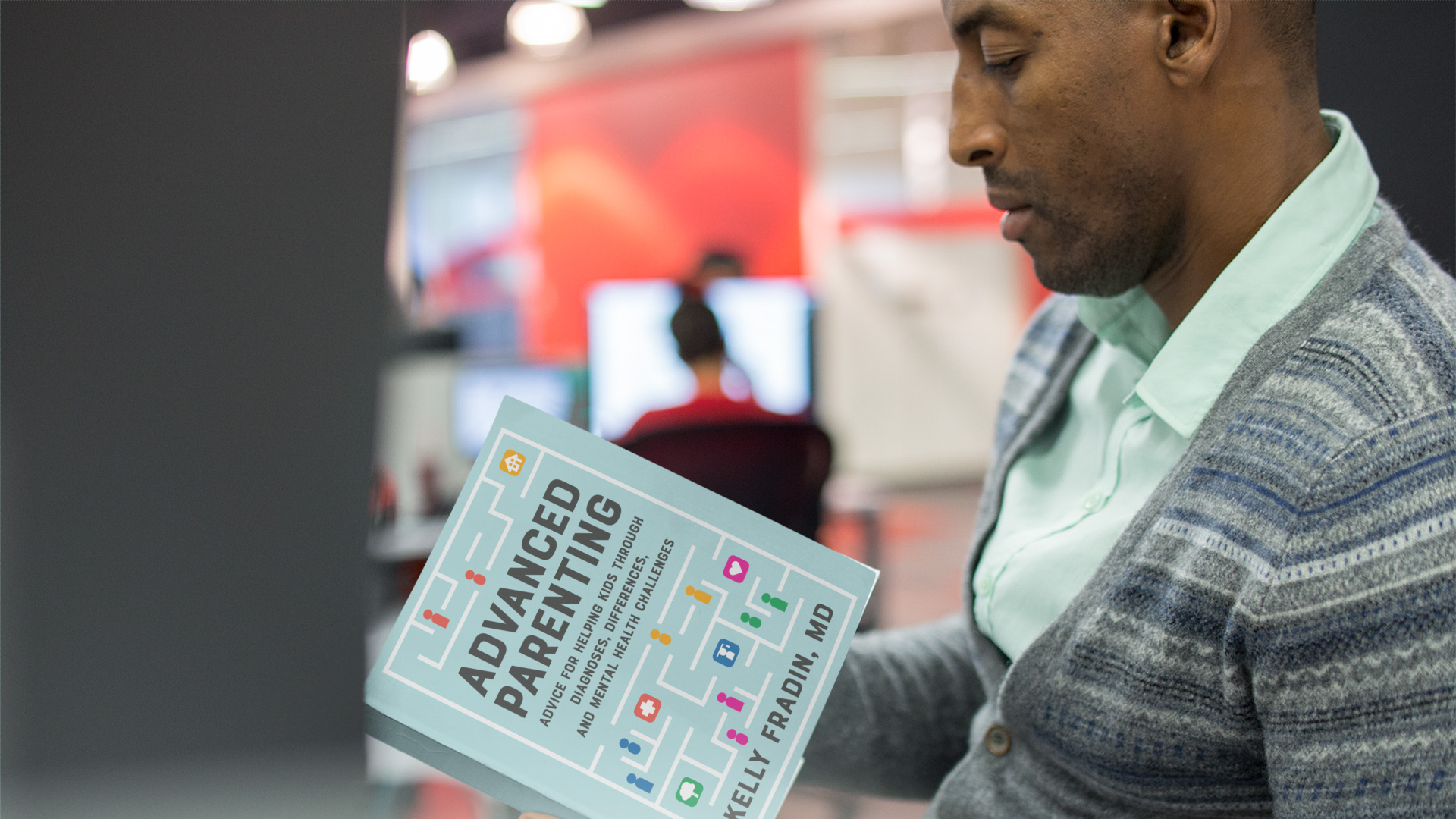

Advanced Parenting: Advice for Helping Kids Through Diagnoses, Differences, and Mental Health Challenges

Kelly Fradin, MD

Balance, an imprint of Grand Central Publishing

336 pages

“Every family has multiple balls in the air,” Kelly Fradin writes in Advanced Parenting. “Some are bouncy balls and if you drop them the show will go on. But others are glass and require more attention to keep intact.”

Those glass balls are the subject of her book, subtitled Advice for Helping Kids through Diagnoses, Differences and Mental Health Challenges. The pediatrician, cancer survivor, mother, advocate and Instagram phenomenon (check out @adviceigivemyfriends) offers realistic advice on parenting children with challenges while preserving one’s own well-being. Early Learning Nation magazine spoke to Dr. Fradin about her perspective and personal journey.

Mark Swartz: There are so many books on parenting. What’s different about Advanced Parenting?

Kelly Fradin: Most parenting books are about so-called typical children with typical problems, but there was nothing out there for when something goes wrong. How do you help parents through that experience? As a pediatrician, I was looking at the parenting shelves and didn’t see books addressing the challenging parts, when things occur that are surprising or unexpected. Parents often feel isolated during that time. I envision them together on the same pathway, working to help their children get the resources they need to live their best life.

Swartz: How should parents of children with health challenges approach guidance about developmental milestones?

Fradin: There’s a lot of content out there designed to educate parents about what to expect of typical development and what the milestones are. This content is valuable because it serves a public health purpose of helping parents to know when they need to get their children a developmental evaluation, or consider having services like early intervention or special education services for 3-5-year-olds.

So it’s a tool, but many parents feel anxious about their children’s development and also kind of feel responsible for it in a way that isn’t always accurate. Pediatricians can help parents to monitor their children and to promptly identify when an evaluation by a developmental expert may be useful. Parents shouldn’t feel like they’re alone or that they have to be an expert on development because we have, in our communities, built in experts who can help them.

Swartz: A lot of parents feel anxious about their children’s development and end up feeling like failures.

Fradin: There’s definitely a lot of anxiety there. Millennial parents seem to take more responsibility over things like this. Social media is part of it, and the apps that let you monitor your children’s development. One of the reasons people get so anxious is that we don’t parent in community settings as much as previously. Many parents don’t spend enough time with enough children of whatever age to know what’s expected and what’s unexpected. I’ve had parents say, “My one-year-old isn’t talking yet.” I have to reassure them that a lot of one-year-olds don’t talk.

Swartz: To what extent does your book draw on personal experience?

Fradin: I’ve come to realize that my own experience with childhood cancer [Dr. Fradin had a rare form of kidney cancer] made me a stronger person and a more empathetic caregiver myself. I have a lot of empathy for people trying to navigate our health care system. It’s quite cumbersome and inefficient. Even with something as simple as physical therapy, you can end up spending a lot of time trying to access those resources and obtain the support you need from insurance or from publicly available programs.

It upsets me to know that the system makes it so hard to access care, and I empathize with a lot of the frustration that parents and people feel when they’re navigating, because I’ve navigated it myself. A lot of the questions I get on Instagram represent holes in our system. These are the questions that people have that they can’t find answers to out there.

Swartz: Those systemic issues come up a lot in the book, and the barriers that families encounter, especially families who don’t have a lot of resources. What did you discover about that in the course of writing Advanced Parenting?

Fradin: Too many parents are thinking, “What’s wrong with me? I must be the problem.” Whereas actually, the system makes it hard. When we talk about the work that parents do as caregivers, we can see the value that they provide in advocating for their children. There’s so much unseen labor that people regard as optional or not valuable.

I interviewed about a hundred parents for the book because I wanted to make sure I gave space to the things that they wouldn’t necessarily bring up during a pediatric visit. And one theme that came up had to do with parents feeling good about helping other parents dealing with the same thing. That help happens through the book, I hope.

Swartz: What are some specific ways that parents help each other?

Fradin: In advocating for their own child, parents can also advocate for all the children who are going to come behind them. They widen the lane and make it a better place. For example, children with chronic conditions used to be asked not to go on school field trips. Maybe there wasn’t the same access to nursing care. But then parents started saying, “That’s not fair.” We have to change the system so that the field trips are accessible by all children, whether they have chronic conditions or not. It comes down to expanding the visibility of this demographic of children and families so that we can all be part of the solution.

Swartz: Inclusion matters.

Fradin: Definitely. That reminds me of a story in my book about a church that didn’t allow children with disabilities to go through confirmation until one child’s family insisted. After that girl was included, the entire church community felt more comfortable bringing their disabled family members. The church became a community hub.

Examples are everywhere. Maybe it’s a school that doesn’t have wide enough walkways, or buses that can accommodate wheelchairs. Everyone can identify systemic barriers that are excluding people from your community—and then take those barriers down.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.