Elliot’s Provocations unpacks current events in the early learning world and explores how we can chart a path to a future where all children can flourish. Regarding the title, if you’re not steeped in early childhood education (ECE) lingo, a “provocation” is the field’s term—taken from the Reggio-Emilia philosophy of early education—for offering someone the opportunity to engage with an idea.

We hope this monthly column does that: provocations are certainly not answers, but we hope Elliot’s Provocations helps you pause and consider concepts in a different way.

I dislike the economic case for child care. I’m not talking about my take on the role of employers, but the near-constant way lawmakers and advocates of both parties rest their case for supporting child care on its function as an economic driver. Instead, I think we need to reposition child care as essential to family freedom and national prosperity – a driver of societal health and well-being.

The nuance is that, of course, child care is an economic driver. But here’s the thing: if the primary reason we need a child care system is to allow parents to work, then the policy target quickly becomes what I call the minimum viable child care system. That is not equivalent to—is, in fact, in direct opposition to—a sustainable, high-quality child care system that works well for parents, educators and children.

Consider child care educator wages. They are miserably low, a median of $14 an hour (~$29,000 a year). They have been miserably low quite literally for decades. “Worthy Work, Unlivable Wages” is a report that came out in 1989. You can find headlines from the late ‘90s— “Child Care Workers Stuck in Salary Limbo”—that could’ve been written yesterday. Nothing has changed because the industry muddled along. Child care has long been in market failure, but it’s frankly a failure the broader market has been willing to tolerate, like a business accepting a certain amount of inventory shrinkage.

There were staffing shortages that led to slot shortages, but the pain was modest enough to evade real action. Prior to the pandemic, there were still over 1 million formal child care workers. Nowadays, the argument—an argument I have made quite explicitly myself—is that because other low-wage sectors have raised their base compensation, child care can’t keep up. The shortages are getting worse, the pain deeper. Tolerance wanes.

Yet follow that to its logical conclusion: if child care offering $12 an hour used to be OK while programs were competing against the McDonalds and Walmarts of the world also offering $12 an hour, and now McDonalds and Walmart are offering $17 an hour, then all we have to do is get child care up to $17 an hour. Right? Minimum viability. There is no broader case.

Because economically speaking, the quality of the day-to-day interactions between a child care educator and a toddler are of little concern. Whether that educator is making poverty wages and can barely keep a roof over her head and the heads of her own children is immaterial. Whether the parent feels comfortable with the child care situation is immaterial. Care itself is immaterial. So long as there is a warm body in that classroom and the meat packing plant worker doesn’t have to miss his shift, The Economy has not been harmed: our investment is returned.

That is perhaps a bit hyperbolic, but not exceptionally so. The very first American child care programs (which followed on from the first child care workers, enslaved Black women) were little more than miserable holding pens for the children of ‘unfortunates’: poor and widowed mothers. As one report puts it:

“They were crowded, marginally funded, staffed by untrained personnel, and barely able to meet minimal standards of sanitation. Furthermore, as [historian Emily] Cahan points out, they were never really ‘for the children.’ They were initially established to help the mothers. Then, during the depression, they mutated into the Works Project Administration emergency nursery schools, the primary purpose of which ‘was to provide work for unemployed teachers, custodians, cooks and nurses.’ Serving the children was definitely of secondary concern.”

This somehow managed to be an improvement over the alternative, which was keeping these young children locked in a room all day or letting them loose in dangerous workplaces. All to say, American child care rests quite literally on a foundation of labor exploitation and a desire to put in the least amount of funding possible.

Low Wages Everywhere

The modern economic case for child care certainly shows more awareness that young children require a safe and nurturing environment and that there is economic value in healthy child development. But the exploitative nature of the sector remains.This is, importantly, not a uniquely American phenomenon. Even in countries like Canada and Germany that have made major child care investments in recent decades, there are huge supply shortfalls. Why? A persistently underpaid workforce!

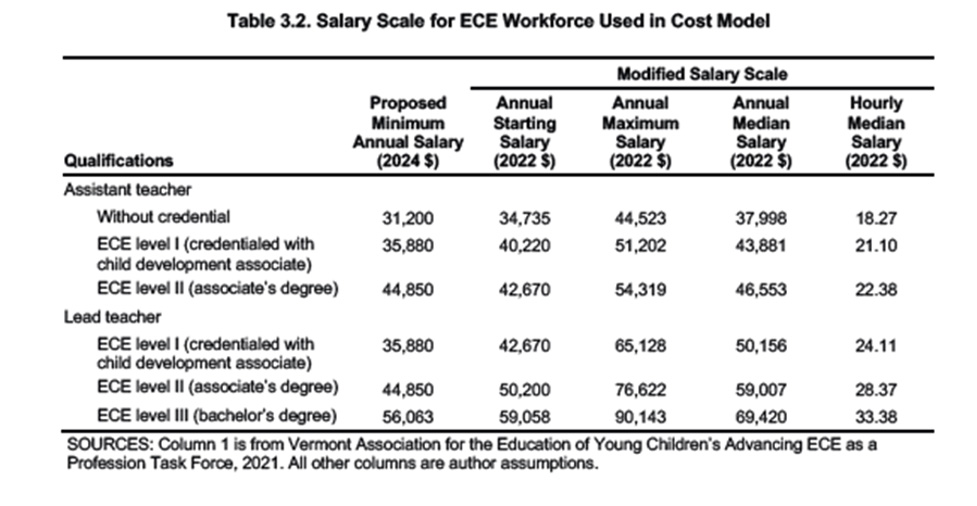

This is more understandable when you consider what it means to avoid the minimum viable system. The Vermont legislature commissioned a study by RAND that asked, among other things, what would a salary scale look like that was equivalent to K-12 educators?

Check out the annual median salary column. These are reasonable salaries that circle the middle class, particularly if paired with reasonable benefits like health insurance and retirement. A two-earner family with an early childhood lead teacher and an electrician – neither of whom may bear a four-year college degree – could easily pull in around $100,000 a year. The game changes.

Yet, again, the economic-productivity case for child care does not suggest why we would ever actualize a salary scale that looks like that! After all, if we are seeking a healthy return on investment, then paying more money into the system than is strictly required to keep a not-terrible amount of slots open is a poor investment. (Indeed, while Vermont put in a truly impressive amount of new child care funding, they rejected RAND’s scale and largely punted on wages).

We are, moreover, breathtakingly bad as a country at putting enough public money into systems that very obviously provide a net positive return. Emergency medical technicians—the people saving workers’ actual lives, if we want to cast this in cold economics—make a median salary of less than $36,000 a year. If we can’t convince policymakers to get EMTs a decent wage, I’d gently submit we are deluding ourselves to think we’re going to get them there, without a forcing function or change in strategy, for a profession that many still see as babysitting.[1]

It is worth reiterating that even in countries with far more progressive governments and far stronger labor unions, child care educators suffer poor wages. Why? Tim Jackson, Director of the U.K.’s Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity, put it this way in a recent speech:

“In the so-called social contract of neoliberal economics, wages follow productivity. Because care takes time, care workers are condemned to pitiful wages, insecure jobs, impossible working conditions and—pandemic aside—the lowest ranks in the status game played out in modern society. Capitalism condemns care, not accidentally, not inadvertently, but systematically.”

(I would add two things: first, the wages-follow-productivity idea that drives much of modern economics is very much a myth; just look at CEO pay. Second, we cannot speak about how care is treated without acknowledging the fact it is overwhelmingly performed by women, and gendered expectations around care—care that is “valorized but not valued,” per scholar Emma Dowling—exist even in the most ‘equal’ of societies.[2])

Jackson’s conclusion is, I suspect, one reason it has been difficult for U.S. child care champions to fully embrace stay-at-home parents and relative caregivers in major policy proposals. It is hard to simultaneously make an economic growth argument and fully honor care. Making it easier financially for a parent or grandparent to provide care for their (grand)child is incoherent in the language of economics. Financial metrics and media coverage do not capture the human development value proposition when a grandmother is paid to provide care as opposed to being a Walmart greeter.

Indeed, to see the ultimate hollowness of overfocusing on economic production, consider elder care. A dementia-stricken 85-year-old is no longer producing, and will never again produce, anything of significant economic value. Yet it is clear to most that we would be morally impoverished, indeed give up a bit of our national soul, to simply cast that person aside.

I do not want to swing the pendulum too far in the other direction or suggest we entirely throw out economic logic. Jobs, particularly good jobs with decent compensation, can be important sources of meaning in people’s lives. As we saw with the Great Recession, the state of the economy matters; the effects of that downturn on individual and family well-being appear to be deep and long-lasting. Moreover, women having access to jobs translates to financial empowerment, the ability to resist coercion and can influence egalitarian political and cultural change.

The lack of child care is absolutely a barrier to parents, especially mothers, having jobs and careers they desire. The economic productivity argument, though, cares little for the quality or stability of jobs, cares little if working conditions support health and flourishing. The idealized image of the growth economy is not empowered women but a stock market rising with no end in sight – a goal that generates a gravity well of minimum viability.

To transform child care, then, we must reposition it in the American mindset – beyond babysitting, beyond a bridge to work.

Recasting Child Care

To get away from the minimum viable child care fallacy we must do two things: first, explicitly position child care among higher ideals than mere work enabler; and second, crafting policy proposals aligned with such a vision.

As Tim Jackson asserts, what’s needed for a paradigm shift is “not just to rail against capitalism—though that of course is one of great joys of our time.” Instead, Jackson says, insomuch as we talk about the economy, we should talk about the well-being economy. He explains (speaking here largely of health care, but entirely applicable to child care):

“Our job is to reconceive economy as care … To build some concept of universal basic services. To protect the rights, wages and living conditions of care workers. To reform the distorted productivity that robs care of meaning. To constrain the rent-seeking behavior of private firms intent on extracting value from people’s infirmity … Our job is to build a new myth better suited to our human condition as a mortal species on a finite planet on the edge of an inhospitable galaxy in the middle of a mysterious universe…”

The first element of a new narrative starts with a change in the way advocates and elected leaders talk about child care. Instead of talking about child care as essential for economic growth, talk about it as essential for families and children being who they want to be, as essential to the national character, as essential as the public schools voters already support.

Public education offers an instructive example worth spending some time on. Schools absolutely allow parents to work, but that is almost never the primary case made for their existence. Horace Mann, often considered the father of American common schools, once argued of education, “The general utility of knowledge, also, and the higher and more enduring satisfactions of the intellect … impart to this subject a true dignity and a sublime elevation.” Even Mark Twain offered that “out of public schools grows the greatness of a nation.”

The argument for public education has variously (and with various levels of problematic-ness) been made on grounds of democracy, global competitiveness, social mobility, innovation, workforce development, cultural assimilation, self-discovery, and, yes, the need to keep children off the streets during the day. When the New York Times ran a feature in 2022 entitled “What is School For?” they featured 12 writers’ answers, which ranged from “economic mobility” to “hope.” None focused primarily on school as a work support. Because school rationales have always included higher ideals, there is little appetite for a minimum viable education system. [3]

Don’t get me wrong, the American education system is badly inequitable, and teachers are absolutely laboring under difficult conditions without great salaries, particularly in high cost-of-living cities. But relatively speaking, teaching is a solid job that offers family-sustaining salaries and adequate benefits. Every state constitution includes an obligation for the state to provide universally accessible, free public schools. Every family has a slot. The nation spends over $700 billion(!) a year on K-12 education. It is the largest or second-largest line item in all state budgets. The median pay for teachers is slightly north of $61,000 a year.[4] Even roiled by culture wars and debates over funding mechanisms, voter support for public education remains sky-high.[5]

You can tick off every single point for spending $700 billion on K-12 education and apply it to the early years and to care and education services outside the school day and school year. Voters are already on board with funding a high-quality child care system. They just don’t know it yet.

Elevating child care into the loftier reaches of the public’s imagination does not, however, have to rely on educational rhetoric. There is a strong case to be made that care is wrapped up in that most American question: self-determination. A wise politician might ask parents the following:

Shouldn’t you be able to spend time playing games with your children rather than frantically refreshing summer camp registration pages in January? Shouldn’t the number of children you have be entirely a question for you and your partner, not one the government influences by making care unaffordable? Shouldn’t you be able to go to church with your family rather than working an extra shift just to pay for care? Shouldn’t your child be supported in learning from birth, not from an arbitrary age cut-off? Shouldn’t you have support outside the school hours that are comically mismatched to your work hours? Shouldn’t you be able to choose the care situation that works for your family rather than having your hand forced into one you’re uncomfortable with? Shouldn’t you be able to do the work you’re passionate about—be a doctor, a firefighter, start a business if you want to—knowing your children are healthy, happy and well cared for? If family is the cornerstone of American greatness, shouldn’t the government support your family like it supports wealthy corporations?

To take this even a step further, support for care is arguably not something families should have to beg from their government, but something owed. The sociologist Theda Skocpol has traced back arguments made in the early parts of the 20th century that mothers—like soldiers—deserve restitution for their immense service to the nation. Skocpol brings up a 1911 speech given by G. Harris Robertson to the National Congress of Mothers, where Robertson inveighed in favor of cash payments to poor mothers: “We cannot afford to let a mother, one who has divided her body by creating other lives for the good of the state, one who has contributed to citizenship, be classed as a pauper, a dependent. She must be given value received by her nation, and stand as one honored.”

(One today may read that as uncomfortably close to defining a woman’s value by her reproductive ability, and it leaves fathers and other family formulations out of the picture. I think we can reasonably update the language while maintaining the core idea that child-rearing provides social value and demands society’s respect and recompense, a tonal shift from pleading for help to ‘how dare you shirk your obligations to American families?’)

Contrast these arguments to the language even some of today’s most stalwart child care champions use. In introducing a relatively modest new child care bill, Sen. Elizabeth Warren stated in the bill’s press release:

“Just like investments in roads, bridges and broadband, investments in child care are critical for families and the success of our entire economy. I have long said that child care is infrastructure and the Building Child Care for a Better Future Act will help secure a strong, long-lasting federal investment in child care to raise wages for workers and ensure affordable and accessible child care for all.”

Again, this logic isn’t wrong, but it is incomplete and ineffective. We have had two-thirds of mothers of young children in the workforce since the late 1990s without an adequate amount of funding to maintain a functional child care system. The economy did not collapse. We have wrung about as much juice as there is out of the economic-growth argument.

One can imagine a media blitz to reinforce the new messages. Television ads with couples explaining that they had to uproot themselves from the town and faith community they loved because they could not find affordable child care. Shots of the inside of a child care center where an educator is joyfully engaging a dozen four-year-olds fading in and out against the inside of school where a Kindergarten teacher is joyfully engaging a dozen five-year-olds: the stinger, “One of these teachers makes $14 an hour. Child care isn’t babysitting.” Or perhaps the same split-screen with big block letters – “Cost to Parents: $0 a year” on one half, on the other “Cost to Parents: $12,000 a year,” fading to the question “Why?”

There are any number of creative options out there, ranging from TikTok challenges (#WhyIsntChildCareFree?), the engagement of influencers from celebrities to the increasingly popular “Dumb Dads.” I am not a PR specialist, and my point is not to propose a particular campaign, nor to propose one specific line of narrative from all I’ve put forth above. Specifics will necessarily be driven by context and audience. My point is to suggest that we are fighting the child care battle on the entirely wrong terms.

Alongside shifts in the zeitgeist must come shifts in actual policy proposals. If I may ask your indulgence to quote myself: “To maximize its popularity, such a plan should help with the early years as well as after-school and summer care, and follow the lead of some Nordic countries with stipends for stay-at-home parents. The simplest, strongest plan to capture the public’s attention could be to mimic the public-school system, and propose universal and free child care. Ideally, any plan would be tied into a suite of pro-family policies that includes paid family leave and a monthly allowance for helping with general child-rearing costs.”

Whatever the particulars of this next generation of proposals, they must be grounded in the fundamental ideas that child care—indeed all care—is patriotic, care makes America stronger as a nation and as a people, and care’s relation to economic growth is a secondary benefit rather than its primary purpose.

I want to close with the words of Robert F. Kennedy, who gave a speech in 1968 declaiming:

“Too much and for too long, we seemed to have surrendered personal excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things. Our Gross National Product, now, is over $800 billion dollars a year … Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.”

A child care system built in pursuit of improving labor force participation and corporate productivity begets child care policy built in pursuit of the minimum viable system. A child care system built in pursuit of healthy, prosperous, and free children and families—upon which rests a healthy, prosperous, and free nation—begets child care policy of which America can be proud.

The choice is ours.

[1] Indeed, this issue of low wages – which is tied up with questions of worker power – dogs many large U.S. industries and has all sorts of nasty societal implications. For more, I recommend Michael Lind’s new book, Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages is Destroying America.

[2] Michael Lind has much to say on the wages and productivity canard. For more on the caregiving points, see Emily Kenway’s book Who Cares: The Hidden Crisis of Caregiving, and How We Solve It

[3] The success of K-12 schools in this regard has created frankly bizarre lines of demarcation. If a program is lucky enough to come under the umbrella of being perceived as “education,” the public dollars flow. Public Pre-K teachers who work in schools have by far the highest wages and lowest turnover of any early educators. But that means a program down the street serving similar—or even the same!—ages get a fraction of the funding. Non-school-based child care educators with bachelor’s degrees are paid as little as half as much as their school-based counterparts. To the five-year-old born in August, a true dignity and sublime elevation; to the one born in November, a way to allow working parents to do their job.

[4] This pay rate did not happen by accident. The history of teacher’s union organizing is long and complicated, but these unions have been on the scene since the turn of the 20th century. Whatever you think of the National Education Association (NEA) and American Federation of Teachers (AFT) today, the fact is they have consistently—and successfully—fought for higher pay and better working conditions. There is a labor union side of the story here, to be sure.

[5] The success of K-12 schools in this regard has created frankly bizarre lines of demarcation. If a program is lucky enough to come under the umbrella of being perceived as “education,” the public dollars flow. Public Pre-K teachers who work in schools have by far the highest wages and lowest turnover of any early educators. But that means a program down the street serving similar—or even the same!—ages get a fraction of the funding. Non-school-based child care educators with bachelor’s degrees are paid as little as half as much as their school-based counterparts. To the five-year-old born in August, a true dignity and sublime elevation; to the one born in November, a way to allow working parents to do their job.