Elliot’s Provocations unpacks current events in the early learning world and explores how we can chart a path to a future where all children can flourish. Regarding the title, if you’re not steeped in early childhood education (ECE) lingo, a “provocation” is the field’s term—taken from the Reggio-Emilia philosophy of early education—for offering someone the opportunity to engage with an idea.

We hope this monthly column does that: provocations are certainly not answers, but we hope Elliot’s Provocations helps you pause and consider concepts in a different way.

As the child care sector hurtles into a painful period of fee increases and closures, you’d be forgiven for missing some good news coming out of California. On Sept. 15th, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a series of bills that committed $2 billion in state money for child care. Among other things, these bills will boost provider pay by about 20% and, as KQED reported, create the “the nation’s first retirement fund for the union representing more than 40,000 family child care providers and continuing to pay for their health care and professional training.” Amid major union actions in the auto and entertainment industries and a historic looming strike by health care workers, I want to talk about the role of unions in child care.

First, some context-setting. Child care unionization is extremely scattershot. There are a few large family child care unions in states like California and Illinois, and a bare handful of center-based unions. As The Hechinger Report noted back in 2020: “The child care industry, which is made up of many small businesses with high employee turnover, is largely nonunionized. Just a quarter of home-based providers belonged to an association or a union last year, according to a survey conducted by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California, Berkeley.”

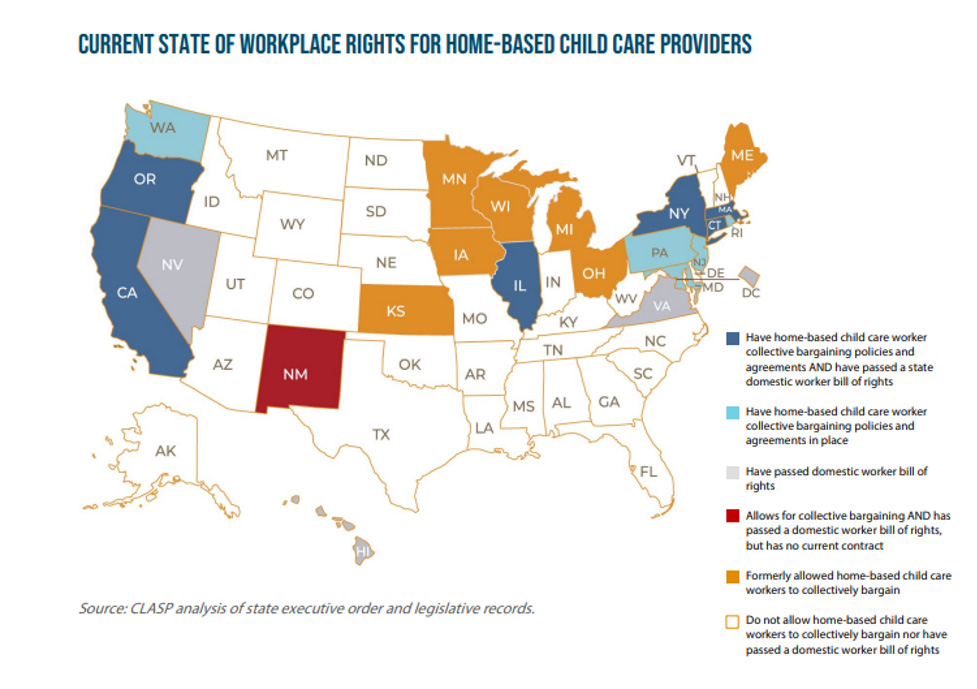

Because most centers are either single sites or small local chains, unionization is difficult. That said, none of the large corporate chains–Kindercare, the largest, has over 36,000 employees–have seen significant unionization efforts.[1] (notably, after employees at a Kindercare center affiliated with the University of Southern California voted in 2016 to become the first unionized Kindercare site, Kindercare coincidentally shuttered the center less than a month later.) In some cases, pre-K educators who work at school-based sites are folded into teacher’s unions. Family child care providers may have an easier time because they can collectively bargain against their state government in search of a better contract, as happened in California. However, as the think tank CLASP has shown, in much of the country family providers have no legal ability to unionize:

The effectiveness of what unions do exist in child care suggests how important they can be. The CLASP report notes examples from early educators in New Mexico gaining hazard pay during the pandemic to those in Rhode Island getting the right to Spanish language liaisons at the state’s Department of Human Services, which oversees child care. The retirement fund won by California’s union, Child Care Providers United, sets a national precedent.

Unions, by dint of their organizing prowess, can also help the sector writ large flex its muscles. This has been very apparent overseas, as unions in places like Ireland and Finland have been instrumental in their respective child care policy progress. It is also the case on a smaller scale in the U.S.; for instance, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) was one of the participants in Connecticut’s successful ‘Morning Without Child Care’ effort. The presence of unions also opens the door to what is known as “sectoral bargaining,” where an agreement is reached that covers an entire workforce. One form of sectoral bargaining just concluded in California, where all fast food workers will now have a $20 per hour minimum wage.

To be clear, unionization is not a panacea. While technically even the employees of small businesses like single-site child care centers can unionize, the barriers to such actions tend to be high. Moreover, unions sometimes work at cross-purposes to other stakeholder groups and even other unions. In New York City, three different unions variously represent school-based pre-K teachers, community-based pre-K teachers, family child care providers, Head Start teachers, and certain child care center directors. This can understandably lead to messiness.

Nevertheless, unionization should absolutely be a bigger part of the child care conversation. The strategy has been around for a while—the first recorded instance of child care union is in 1949, and there was a unionization guide published by the Child Care Employee Project in 1986—but it has rarely been front and center. Increasing unionization opportunities will require a basket of different tactics, from advancing more state laws that authorize collective bargaining by family child care providers to center-based educators working to build support among employees of the big corporate chains. Such efforts will also require financial backing from philanthropies and other sources. In this year of high union activity, there may be no better moment to start charging up child care educator power – power that will be badly needed in the battles to come.

[1] A 2021 Reddit thread about unionization, with comments by employees of some of the large child care chains, makes for fascinating reading.