Shantel Meek, Ph.D., founding executive director of the Children’s Equity Project at Arizona State University, learned an important lesson during the creation of the new report, Start with Equity Arizona: “There is actually a comment capacity limit in Google Docs,” she laughs. “We broke Google Docs and had to copy it all over into a new doc and resolve all the old stuff because there was so much back and forth.”

The result of lively and sometimes heated exchange among its seven co-authors, the report underscores ways that Arizona can better serve its youngest residents and their families. Early Learning Nation magazine interviewed Dr. Meek about the challenges the state’s early learning landscape faces and the opportunities to learn from other states.

👉Download “Start with Equity Arizona: Expanding Access, Improving Quality, Advancing Equity”

Mark Swartz: This is your third Start with Equity report, right?

Dr. Shantel Meek: Yes, we published our first, Start with Equity: From the Early Years to the Early Grades in 2020. It dug deep on a national scale on discipline, inclusion of kids with disabilities and dual language learners (DLLs). We looked at the data on how kids are faring and at the research into what works to support and address some of the disparities that we’re seeing. The report also included a policy agenda and recommendations. Later the same year we came out with Start with Equity: California, which coincided with the state’s creation of a Master Plan for Early Learning and Care, and a lot of our recommendations either aligned with or, indeed, informed that initiative.

Swartz: CEP is based in Arizona State University, so this report is a homecoming.

Meek: I actually grew up in these systems that we’re talking about. I went to public schools my whole life, including through my graduate degree. I have my own kids now, one in the K-12 system, and one in the early care and education system. And so that certainly raises the stakes, increases my focus, makes me angrier.

Swartz: Where are the gaps in Arizona?

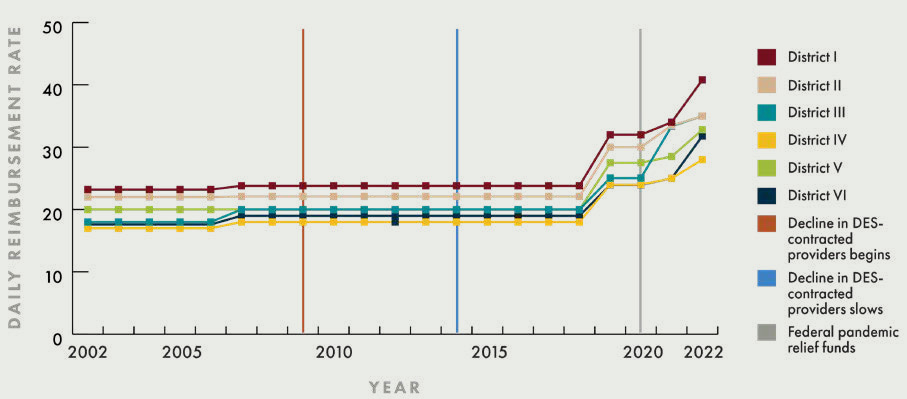

Meek: I’d say we have major gaps across all three big domains we focused on in this report—equity, access and quality—all stemming from poor policies and chronic underinvestment. When Jan Brewer became governor in 2009, they zeroed out funding for child care in the state’s general budget. And we’ve never recovered until the 2019 infusion of resources from the feds came in, and then the pandemic funding.

After years of outdated, stagnant child care reimbursement rates, Arizona saw a plummet of contracted providers with the state, probably not surprisingly, which results in families having fewer choices, which may result in kids who are using subsidy, likely being served in more segregated settings because there’s fewer of them. We don’t have a public pre-K system in the state that meaningfully provides access to three- and four-year-olds.

On the quality front, we’re behind on basic policies like ratios and group sizes and overlook entire populations of kids, like dual language learners, which make up nearly half of the state’s young children. So I think all of those are underlying challenges.

Swartz: What about the state’s Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS)?

Meek: The QRIS captures important dimensions of adult-child interactions. But it also ignores many of the issues that disproportionately impact kids from historically and contemporarily marginalized communities. Almost half of the young children in the state are DLLs, but our QRIS doesn’t even mention them.

Communities like the one where I’m from and across the borderlands have a much higher percentage, but practices and policies that really impact their early experiences—like dual language instruction and building their bilingualism—are not really considered as part of the broader quality system. Inclusion of kids with disabilities is not measured or required as part of participation in the quality system. Exclusionary discipline policies, which disproportionately impact Black children, are not part of the system.

At the end of the day, what we “count” in rating systems, is what we value, what we resource. And if we don’t “count” the structural or process-oriented dimensions of quality that really matter to children with disabilities, to emerging bilinguals, to children of color—then the system wasn’t built for them. And that’s a problem.

Swartz: It doesn’t sound like the state is doing enough to support DLLs.

Meek: I’m Mexican-American, grew up on the U.S.-Mexico border speaking English and Spanish. My kids are growing up bilingual a couple hours north of where I grew up. So this is certainly very close to home. We have mountains of evidence to suggest that bilingualism and biliteracy is associated with a host of positive short- and long-term outcomes—across cognitive development, social emotional development, academic, school-family partnerships, college-going, earnings, even health. We know dual language education, where children learn English alongside a partner language—usually and ideally the home language, is associated with a number of academic advantages.

Still, an early learning program operating in my hometown of Nogales, where maybe 90% or more of children are growing up speaking Spanish exclusively or in addition to English, can offer instruction exclusively in English and be considered of the highest quality—5 stars. It doesn’t matter that it’s wildly out of alignment with research because what you don’t count doesn’t matter.

👉One Way to Make Universal Preschool a Reality—Head Start for All (Hechinger Report)

Swartz: And this is in a state where one-third of the residents are Latino.

Meek: Arizona is the last remaining English-only state in the nation. That applies to K-12 systems, not to early education, but it does create a climate where in most cases, early education has to transition these kids to English-only kindergarten.

There’s a disincentive to build on their home language—whether it’s Spanish or an Indigenous language—because of the fear that you’re not preparing them from this harsh, monolingual system that they’re about to transition into. The state superintendent for education recently filed a lawsuit because several school districts, including the one where my daughter goes, allow English learners into bilingual education or dual language programs. It’s a really hostile, center-stage issue in the K-12 space that certainly trickles down to early education. Not surprisingly, these policies have created a system where our English-learners are not set up to succeed, resulting in some of the worst graduation rates in the country.

Swartz: The report also sounds the alarm about children with disabilities.

Meek: Yes, there are gaps across the system when it comes to serving children with disabilities. Take licensing, for example. There is no prohibition on excluding children with disabilities from child care settings. Programs often cite toilet training policies as a reason to exclude children with disabilities from their programs, as these kids are sometimes potty-trained a little bit later than their peers without disabilities. And training to support and serve kids with disabilities isn’t required in licensing.

While there is an inclusion coaching program in the state as part of the quality improvement system, it’s optional, so most of the regions in the state choose not to fund it. On the child care front, less than 1% of child care subsidies are going to kids with disabilities when the CDC says that about 1 in 6 kids has a developmental disability.

Swartz: How do you define equity?

Meek: First and foremost, everything we do is informed by history, by an understanding of the roots of contemporary inequities and disparities. Then, at a systems level, we look at three things: access, experience and outcomes. Equitable access comes down to who gets in the door in the first place. Experience encapsulates everything from the teacher-child interaction to discipline, to praise, to the language of instruction. And outcomes refers to what our investments in programs and services make possible across various demographic groups.

👉Discover the Start with Equity Fellowship

Swartz: How about quality?

Meek: We titled our QRIS report Equity Is Quality, Quality Is Equity. They are one and the same. You can’t have quality if you’re not paying attention to the experiences of kids from historically marginalized communities – who are the majority of kids in some places and the vast majority in some places.

Take, for example, a child care program that is informally excluding kids with disabilities by saying, “Oh, we’re not the right place. We don’t have the right services.” They’re turning away kids, but they could have a 5-star rating. Across the country, there needs to be more understanding of the Americans with Disabilities Act in the child care space, because you’re not allowed to do that.

Think about a program serving all dual language learners and providing instruction exclusively in English. If we don’t count language of instruction as part of the rating system, this program could be rated a 5-star and be unaligned with research on best practices for DLLs. A program could conceivably be rated 5 stars and be expelling or suspending children, but if we don’t count that as part of our rating, families looking for information would never know that.

👉Commonly Asked Questions about Child Care Centers and the Americans with Disabilities Act

Swartz: What are the reasons for optimism in Arizona?

Meek: There are state policy makers in office right now who have expressed support for child care, who have expressed an interest in equity, who have expressed an interest in really doing more for kids with disabilities, for kids who are bilingual and growing up bilingual, on discipline and other issues where we see racial disparities.

So I think that is promising and I think that’s exciting. The silver lining of being behind other states is that we can learn from them – what they’ve done right, what we want to avoid. There’s still time to build a mixed-delivery, high-quality birth-to-five system that meets the needs of all our kids.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.