Elliot’s Provocations unpacks current events in the early learning world and explores how we can chart a path to a future where all children can flourish. Regarding the title, if you’re not steeped in early childhood education (ECE) lingo, a “provocation” is the field’s term—taken from the Reggio-Emilia philosophy of early education—for offering someone the opportunity to engage with an idea.

We hope this monthly column does that: provocations are certainly not answers, but we hope Elliot’s Provocations helps you pause and consider concepts in a different way.

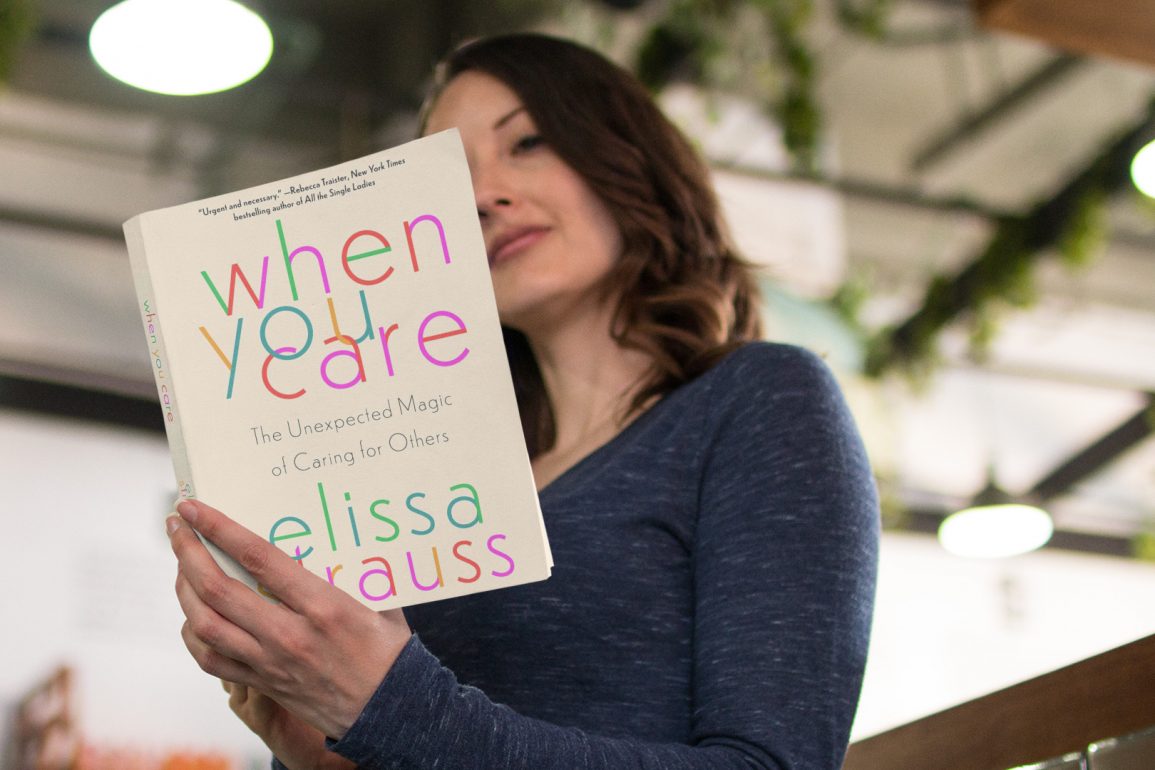

In our talk of care, we frequently focus on questions of where, who and what. We rarely ask questions of why we care and what it means to care. Similarly, much of the modern care conversation centers around (very real!) struggles and scarcity. That’s why I was so pleased to read journalist Elissa Strauss’ new book, When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others. Strauss not only explores the positive benefits of caregiving, she raises previously submerged questions around the philosophy of care and its implications for American culture and policy. To learn more, I called up Strauss for a Q&A. The transcript of our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Elliot Haspel: First off, tell me: Why did you decide to write this book?

Elissa Strauss: So, it really came from two almost contradictory places that came together in the end. On one hand, I reported for years all about why we don’t have paid leave, why don’t we have universal and affordable child care or eldercare, why is there still so much maternal discrimination in the workplace, why are too many moms still dying during labor? So, all this stuff that moms, and caregivers more broadly, had stacked up against them in society. And part of me felt like I got to a place where I couldn’t write one more paid leave article—I’m absolutely, very glad other people are still beating that drum!—I wanted to dig deeper. And I thought, you know what, there’s something else that I could be focusing on: the cultural roots of the care crisis.

Track two was that when I became a mom in 2012—and I think this is still alive and well—there was very much a sense that it was not cool to like motherhood. You had Rachel Cusks’ A Life Work being passed around a Brooklyn playgrounds like ‘I’m handing you the truth,’ and that’s a book that really presents motherhood and selfhood as a zero-sum game. And look, I don’t wanna come down against the burden narrative of motherhood, because I think it’s important to also talk about the stresses, especially in the United States. But it felt like there was so much of it.

It took me a beat to realize actually these things are connected. I was writing about why our society doesn’t value caregiving, but I myself in my life didn’t really value caregiving. I wanted to have kids. I love my son, but I thought I had to partition it off from everything else in my life, in order to be legit.

Haspel: That’s one reason I really appreciate this book. It does come at a different angle than a lot of the books, even the books that I write, which are much more on the policy side of things. You had this fascinating chapter on when women’s movements embraced care, talking about this lesser-known feminist history of women who saw care as something really to be valued. Could you talk a little bit about what you found when looking into that?

Strauss: Yeah, that was some of the most exciting research in the book, that and the whole world of care ethics.

Haspel: Oh, we’re going to get into that, don’t worry!

Strauss: They were the two like, ‘Oh, my gosh, why was this never taught to me?’ parts. So you know, many of the feminisms I cycled through—all important, all which fed me and nourished me, and made a world that I like living in, whether a career feminism or sex-positive feminism or reproductive rights feminism—either they ignored care or they didn’t necessarily have terribly nice things to say about care.

And then when I went digging, I found right there were lots of other feminisms, and they don’t say women should be home, you know. I feel like we’ve been set up by Phyllis Schlafly stuff, we’ve been set up as you’re either pro-women staying home and valuing care, or you’re pro-women leaving the house and seeing care as something that holds women back.

And it turns out there is a third way—and not just one we’re imagining now, but that women imagined a hundred-plus years ago. So, the first time I saw this, historically speaking, was with the fight to get women the vote, and how women actually relied on their authority as mothers and caregivers to make the argument that their voice mattered in the populace, that they needed to contribute to selecting our leaders because they had special insights on account of being active caregivers.

They were called ‘social housekeepers’ or ‘municipal housekeepers,’ and it was a very powerful movement. One named Rheta Childe Dorr wrote that a woman’s place is home, but home is everywhere. Even that feels like such an inversion of all categories we use to think about women’s participation in public life. And you know, these social housekeepers make great gains, in addition to helping successfully get women the vote. They also made sure that there were public playgrounds, children weren’t working, there was clean drinking water.

And, of course there’s a tension: this may not have been palatable if these women didn’t wear the motherhood cloak. But I think to fully take away that care was its own powerful lens to look at, that is demeaning care. To be overly cynical about it and say, ‘well, of course they had to do that because men wouldn’t have wanted their voices if they were trying to be truly equal to men.’ That’s true! Yet, I personally refuse to accept the idea that a bunch of moms or caregivers don’t have interesting things to say.

You know, there were a number of Black feminist leaders that thought like this, especially as welfare became a dirty word because Black women needed it. So, we have Johnnie Tillmon, one of the great welfare activists, and her vision of feminism is one that really makes room for being able to care: when the household needs you and the family needs you, you should be able to do that. It should be a right, not to mention a privilege and a joy.

Haspel: So, I want to jump to the last two chapters and the conclusion, because that’s some of the stuff that honestly stopped me in my tracks a little bit. We’re so used to talking about care in instrumental terms, right? Like what it can do for your ability to work. We lose sight of the bigger questions. Can we start with the fact there is this field of philosophy known as care ethics that is, I think, pretty under-acknowledged and under-appreciated. What is that, and what can we learn from scholars of care ethics?

Strauss: To start very broad, we have these ideas of what it means to be a good person and what it is to do the right thing, and how we figure that out. One of the big ideas is a rules-based way to think about it: We follow, maybe, the Ten Commandments or the classroom rule. So we don’t cheat or steal because ‘thou shall not cheat or steal.’ Or maybe we have a more virtue-based approach to ethics, and we think ‘I have these core traits that are good traits,’ like I am honest. Therefore, I don’t cheat or steal. And then there’s something that’s very fashionable here in Northern California which is a more utilitarian approach, that if you can just data-ify everything you could somehow come up with a formula—not to dismiss any of these, even though some people take it too far—that you could figure out what’s the right thing to do by figuring out what would create maximum good in the world.

So, care ethics comes in, and it introduces something to the world of philosophy that was left out for a long time — and that is relationships. That sometimes the right thing to do is actually rooted in that one and only person before you, and that one and only moment that you’re in. An example I use in the book is around when you have to think about cheating or being dishonest. If your kid had a horrible day of bullying at school, and they had a book report, and it’s ten o’clock at night, maybe you help them more than you usually would, and you think it’s not the best and most right thing, but that is actually the best thing for that relationship. Care ethicists are hardly saying, ‘Oh, relationships should be everything,’ but they want them included in our conception of what it means to do right by others.

Adding to that, once you’re in relationships, it is an area where there are deep ethical and moral epiphanies possible. Through these relationships we learn so much about ourselves, we learn so much about human nature. We can actually cultivate the goodness inside of us.

One of my favorites, Nel Noddings, talks about how the ‘memory of care’ is the foundation of morality for many of us. You know, care was just so left out of conversation for so long. And care is not always this beautiful, harmonious, frictionless place of love and ease. When you have someone you care for, and they’re dependent on you, you do have to privilege them versus other people; it’s just the nature of the game. So how do you balance that? When is that right or wrong? For us, we made the decision to send our kids to private school. We still feel really bad about that, even though we also know why we did it. That’s something that is actually at the heart of care ethics, too: how do our care relationships interact with our other relationships?

Haspel: What really struck me was how deep the implications of a care lens take you. You talk about the founding documents of the United States — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. You have this quote that “care is as fundamental to the good life as justice, but it’s rarely presented in fundamental terms.” It suggests a broader social contract. And that to me is a very interesting mindset shift. So I’m curious: what would be different if we did start to talk about care and more fundamental terms?

Strauss: I’ll go straight to a very concrete thing: we would care for the caregivers. So, justice is seen as ultimately about equality, right? It’s two independent people having a relationship that’s fair. Once you mix in dependency—which was there all along but ignored—,it just doesn’t relate. Like, there’s no justice with me and my children. It’s never gonna happen! So when we really incorporate care, it opens our eyes: there’s something else going on that we’re trying to achieve. That is, making sure all people that are dependent on others have the ability to survive or thrive, or be treated with dignity at the end of their life, which I think is a universal value now. We just forget that dignity happens through a one-on-one relationship; the core element of dignity is care.

So, if care is a core value of our society, we have to care for the caregivers. Dependency is a chain. It’s a natural part of what it is to be human. And when someone depends on you, you’re not independent anymore. So not only is that person dependent, you yourself become dependent. You yourself can’t fully inhabit the world as an independent person anymore. It’s just not how it works, but right now caregivers are expected to live with dependency while living in a world where there’s a total blind spot for dependency. And no one’s made it easier for them, from the smallest things of, if you bring your elderly parent with dementia who moves very slowly to a certain restaurant, people might just get annoyed with you, there won’t be easy access. If you bring children in the public arena in this day and age you often get a stink eye. So caring for the caregivers is about making space for dependency in the public sphere, and also providing that critical support that caregivers need and don’t get — and it’s tragic.