Though national media outlets recently trumpeted the news that workers at a Tennessee Volkswagen plant had voted to join United Auto Workers—groundbreaking in the traditionally union-allergic South—a little farther west, equally momentous successes were taking place.

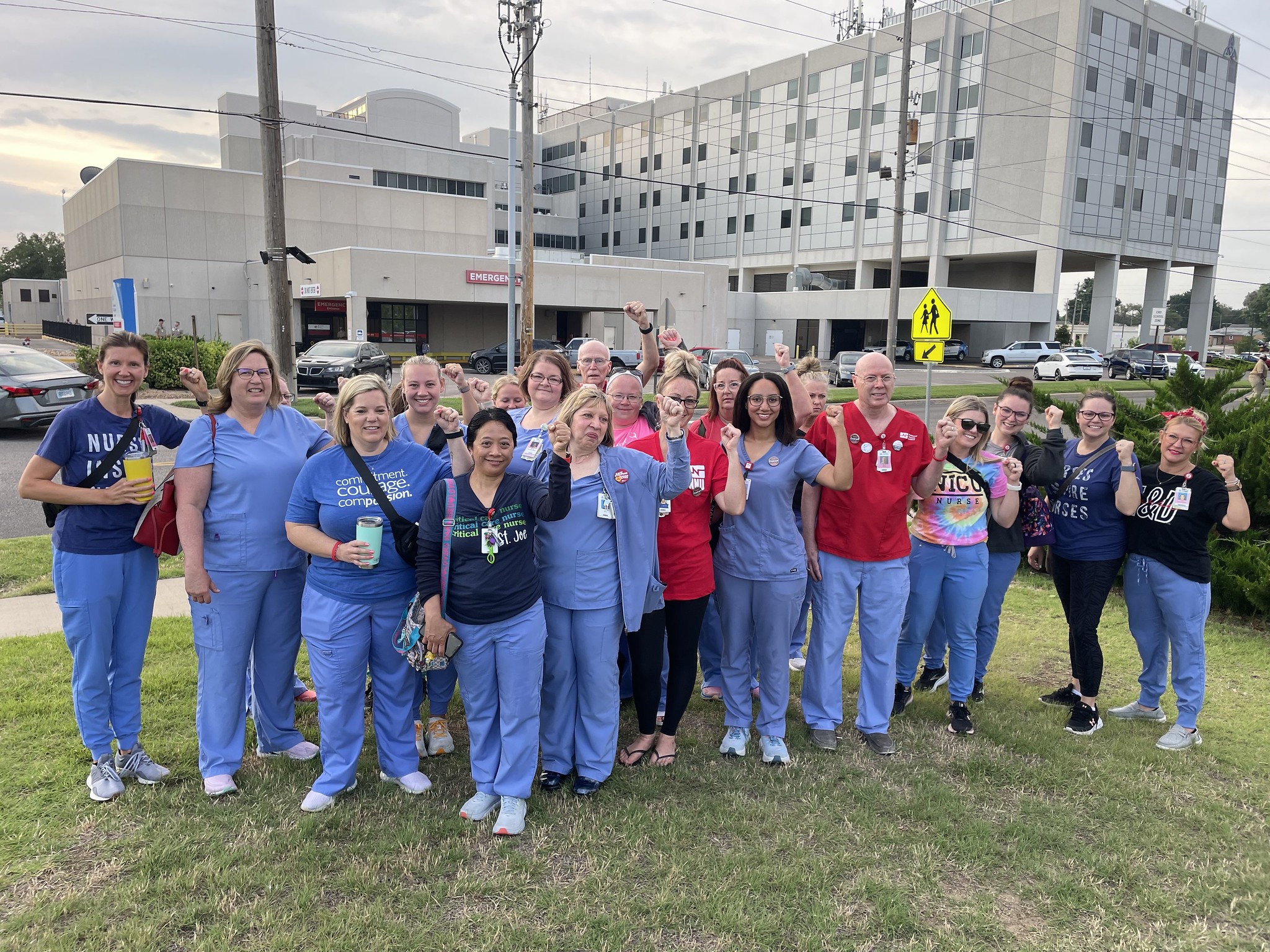

In mid-April, nurses in Wichita, Kansas, ratified their first-ever union contracts with two Ascension health system hospitals. The victory followed a similar win in March in Austin, Texas, when nurses at Ascension Seton Medical Center voted to ratify their first union contract with Ascension. Neither success came easily or quickly, say members of National Nurses United (NNU), the country’s largest union and professional association of registered nurses.

“I don’t think [Ascension] calculated on our determination and resolve to get the results we wanted, and our patients needed,” says Marvin Ruckle, NNU member and a veteran nurse who has worked at Ascension St. Joseph in Wichita since 1989, with 24 of those years in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. “Our community has been so supportive, coming out to our strikes, bringing us food and water. Workers from all the other unions around the Wichita area—steel workers, UPS, Spirit (airplane factory)—joined us. Most of these people have either been a patient or had family in one of our facilities and they know there needs to be change.

“This (contract) is an incredible step forward for nurses, so we can work with the hospital to make patient care better for our community,” Ruckle says. “But it shouldn’t have taken this long. We were determined, we kept pushing, and all Ascension did was drag out the process.”

One of the nurses’ most significant wins was safe staffing ratios enforceable through a nurse-led Professional Practice Committee. In Austin, hundreds of nurses spent more than a year in contract negotiations and organizing efforts, participating in two strikes to focus attention on their demands including guaranteed lower nurse-to-patient staffing ratios. At all three facilities, Ascension management responded to the nearly 2,000 nurses’ historic one-day joint strike on June 27 with a three-day lockout.

Mission-Driven Ascension

Based in St. Louis, Missouri, Ascension is one of the largest health systems in the U.S., boasting 140 hospitals and 40 senior living facilities in 18 states and the District of Columbia. Becker’s Hospital Review listed Ascension as No. 2 in its 2019 list of 100 of the largest hospitals and health systems in the U.S. and the largest nonprofit health system by hospital count. The nonprofit Catholic health system’s stated mission is to deliver “compassionate, personalized care to all, with special attention to persons living in poverty, and those most vulnerable.”

A deeply researched analysis from the National Nurses Organizing Committee and NNU, “Dangerous Descent: How Ascension Betrays its Mission by Gutting Care for Pregnant Patients and Babies,” questions how closely Ascension hews to that mission, particularly in communities with high poverty rates and a disproportionate number of Black and Latino residents. Ascension, the report states, is one of the nation’s worst offenders in closing obstetrics units and obstetrics services. Over the past decade, Ascension has eliminated obstetrics services at 16 hospitals and slashed more than a quarter of the labor and delivery departments that it had been providing in 2012, a rate three times higher than the national average of 6 percent.

Since 2022 alone, Ascension has closed five maternity wards, all health care markets where Ascension maintains a monopoly or near-monopoly on health services. Half of the hospitals where Ascension closed labor and delivery units are in counties with a higher proportion of low-income residents and people of color, and higher rates of infant mortality than the national average (also known as “persons living in poverty, and those most vulnerable”—see Mission Statement above).

Profits over Patients?

By now, the statistics are familiar to anyone paying attention: the U.S. has the highest rate of death among pregnant women and infants of any wealthy country; maternal mortality is more than 10 times and infant mortality almost double the average among comparably wealthy nations. It is no longer even a nasty secret that Black women are nearly three times as likely to die in childbirth as white women.

As “Dangerous Descent” points out, for the first time in two decades, infant mortality has risen in the U.S., largely due to pregnancy-related complications, which experts attribute to limited access to specialists who deal with complicated pregnancies. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 80 percent of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. are preventable—and healthcare leaders have a major role to play in improving these outcomes. Tragically, many systems focus their eye most keenly on the fiscal bottom line rather than the fundamental health of their patients.

Hospital consolidation has been on the march over the last two decades, with more than 67 percent of U.S. hospitals now belonging to a larger system, compared to 45 percent in 2000. NNU’s report cites numerous studies that have shown that such highly consolidated markets can lead to price increases and diminished patient outcomes. Hospital corporations say such consolidation creates “efficiencies” that enable them to cut costs. What they don’t say as loudly is that steps such as eliminating pediatrics units and obstetrics services—both major casualties of hospital cost-cutting—also improves their profits. In practice, consolidating labor and delivery limits access to care for many patients in low-income areas who may not have vehicles or good access to public transportation. Increased distance to medical care can result in missed prenatal appointments or an inability of patients to get to the hospital in time to deliver their babies safely.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, more than 400 maternity services closed in the U.S. between 2006 and 2020. Between March and June 2022, 11 health systems announced they were closing their obstetrics services. When birthing units close, obstetricians and nurse-midwives are more likely to go elsewhere, exacerbating the epidemic of maternity care deserts in the world’s largest and most robust economy.

“What was really striking to us,” says Elana Kessler, author of NNU’s “Dangerous Descent” report, “is that this is a mission-driven hospital system under the Catholic church that is to care for the poor and to create a more just society. Their actions are not in line with that mission statement. By closing labor and delivery units in Medicaid-heavy areas with higher proportions of Black and Latino patients, they’re hiding behind their mission while they’re increasing their profits.”

Health reporting news site STAT News stated in a 2021 investigation that Ascension, “a wealthy, religious, tax-exempt health system,” had migrated toward behaving like a Wall Street firm, using its wealth to create a sophisticated investment strategy that includes a partnership with the private equity firm, TowerBrook Capital Partners. Ascension stands out from other nonprofit hospitals that have dabbled in private equity investing in the sophistication and expansiveness of its $1 billion partnership with TowerBrook, the STAT investigation found.

On its 2021 federal tax return, Ascension reported that CEO Joseph R. Impicciche received a salary of $13 million. In 2022, the New York Times reported that Ascension had spent years reducing its staffing levels to improve profitability even though the chain is a nonprofit organization with nearly $18 billion in cash reserves. At that time, its charity care accounted for 1.9 percent of operating expenses (against a national average of 2.6 percent).

Even with the additional revenue from its investments, Ascension pursued cuts to safety-net hospitals in Washington, D.C., and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, abruptly closing its Labor and Delivery unit in December 2022, leaving Milwaukee’s south side, home to a large immigrant community, completely without a hospital to deliver babies. The move prompted a scorching letter from Wisconsin Sen. Tammy Baldwin, who demanded answers from Ascension on its questionable priorities that funnel cash to its investment funds and executives, putting providers and patients at risk. In her letter, Sen. Baldwin called on Ascension to reinvest its cash reserves in hospitals that serve vulnerable communities and to increase pay and improve working conditions for its “burned out and overextended health care workforce.”

In an April 19 email response to Early Learning Nation magazine, Sen. Baldwin stated that Ascension had replied to her letter. “While I’m encouraged that Ascension appears to be taking the communities’ concerns seriously and working to rebuild relationships,” she wrote, “I remain concerned that their business practices appear more like a private equity firm than a nonprofit hospital whose stated mission is to serve the public.”

Understaffed NICUs and Obstetrics Units

“It’s been like working in a MASH unit,” Ruckle said, describing his experience in Ascension St. Joseph’s NICU. Mobile army surgical hospitals (MASH) units, which were phased out in the early 2000s, were known for their primitive conditions, grueling work schedules and frustrating lack of resources. As reported in “Dangerous Descent,” nurses at multiple Ascension hospitals have noted the perpetual crisis caused by staffing cuts and equipment shortages.

“It’s heart-wrenching to go home and wonder if you were able to help that critically ill baby as best you could and worry that they aren’t going to have the best outcome,” he said.

The result for nurses can be not only stress and frustration but, according to Zenei Triunfo-Cortez, one of NNU’s presidents, moral harm.

“As nurses, we have an obligation to advocate for our patients, to do what’s best for our patients,” she says. “But the situation we’re being put in, especially Ascension nurses, is that we know we have to do the right thing and are being prevented from doing so because of the situation in our hospitals. Then we suffer from moral injury. Our hearts are breaking because we want to do what’s best, but our employers are not providing what we need to do so.

“We start asking, ‘Is this really worth my health?’” says Triunfo-Cortez, who has been a registered nurse for 44 years. “The majority of our nurses will be out there fighting for our patients and fighting for what’s right, but it does make us question.”

Recommendations from NNU

Pointing out that Ascension enjoys hundreds of millions of dollars in tax breaks thanks to its nonprofit status yet continues its abandonment of low-income mothers, parents and newborns, NNU and the National Nurses Organizing Committee recommend systemic changes that would align Ascension with its mission:

- Come to the table and listen to nurses; staff every unit to ensure the best care for patients.

- Commit to reopening closed labor and delivery wards.

- Provide obstetric services at all new hospitals Ascension opens or acquires.

Ascension has the opportunity and resources to become an industry leader, says Kessler, the report’s author. “As nurses advocating not only for nurses but for the patients they serve, we know that safe staffing and readily accessible care are completely entwined in the work nurses do—they’re one and the same.

“Ascension will say, ‘Consolidation is part of our business strategy. It’s better for the patient,’ but at the end of the day,” she says, “it doesn’t happen that way. It creates barriers for patients to face—transportation, child care—and when there is not ready access to obstetrics services, pregnant patients are less likely to get prenatal care, which then has a cascade of harmful effects.”

Ascension’s 1 in 50 Report

In late April, Ascension released a Maternal Health Report in which it reported that one in 50 U.S. babies is now born at an Ascension hospital, no doubt in part to what The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) cited as the corporation’s role as the “most active dealmaker” in its review of nonprofit hospitals’ expanding into wealthy areas while shunning poorer ones. Nonprofit hospitals now account for half the $1 trillion U.S. hospital sector. Across the sector, the WSJ’s investigation found, though they receive local, state and federal tax breaks in exchange for providing charity and benefiting communities, nonprofits are less generous in providing aid than their nonprofit rivals.

Though the Ascension report states that its commitment is “rooted in the loving ministry of Jesus as healer” and the 32-page report details positive health outcomes throughout the system, NNU’s Kessler says the report doesn’t tell the full story of how those numbers arrived.

“Outcomes for patients no longer served by Ascension wouldn’t be included in the hospital’s data, so the report is incomplete,” she says, “failing to consider the impact on communities where Ascension has shuttered obstetrics services under the corporate strategy of ‘consolidation.’

“Ascension asserts that one in 50 babies are born in their care, which only underscores the importance of Ascension keeping obstetrics services open for the thousands of expectant mothers they serve each year. Furthermore, a snapshot of data from one year, in one health system, doesn’t tell the whole story of the impact of Ascension’s decision to close services. It should also be noted that Ascension’s expansion into wealthier communities could weigh the data in favor of showing better than average outcomes.”

RESOURCES

Dangerous Descent: How Ascension Betrays its Mission by Gutting Care for Pregnant Patients and Babies National Nurses United’s report on how Ascension is using its market dominance to shut down its labor and delivery units.

Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses An association that empowers and supports nurses caring for women, newborns and their families through research, education and advocacy. The organization offers nurse resources, education, professional development, and advocates on policies and issues of importance to the 350,000 nurses working in health, obstetric and neonatal nursing across the U.S.

JAMA Forum Maternity Care Deserts in the U.S. Describes the growing scarcity of childbearing services and introduces two strategies that could reduce maternity care deserts.

March of Dimes Maternity Care Deserts Report Nowhere to Go: Maternity Care Deserts Across the U.S. (2022 Report) Provides an interactive map detailing access to maternity care throughout the U.S.

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.