The scene is familiar the world over: a parent speaks to their baby in that high, singsong voice we now know as “parentese;” the baby reacts with wide, interested eyes and maybe a bit of babble of her own, which brings the parent in to smile warmly, peer into those baby eyes and keep the conversation going. With every glance and coo, the parents are saying, “I’m here. You have my attention.”

These moments of connection are sweet, emotional encounters, but researchers know they are much more. Research scientists at the University of Washington’s Institute for Learning & Brain Science (I-LABS) recognize this “social ensemble” as the nascent conversational turns that lay down the pathway to language—the gateway to connection, education and the world of ideas. Given that these distinctive interactions appear to be universal and uniquely human, I-LABS researchers wondered what their developmental purpose could be. What they found was not only that the babies’ brains “lit up” during these interactions, but that the degree to which individual babies responded to social interactions predicted the child’s language growth beyond 2-½ years of age.

“What we were trying to see is whether that social ensemble—the parentese, the warm smiles, the touches, and the back and forth that says you’re paying attention—has a (developmental) goal in addition to the emotion that’s connecting these two people,” says Dr. Patricia Kuhl, I-LABS’ co-director, and holder of the Bezos Family Foundation Endowed Chair in Early Childhood Learning, who led a groundbreaking longitudinal study linking infants’ individual brain responses to social interactions and their future language development.

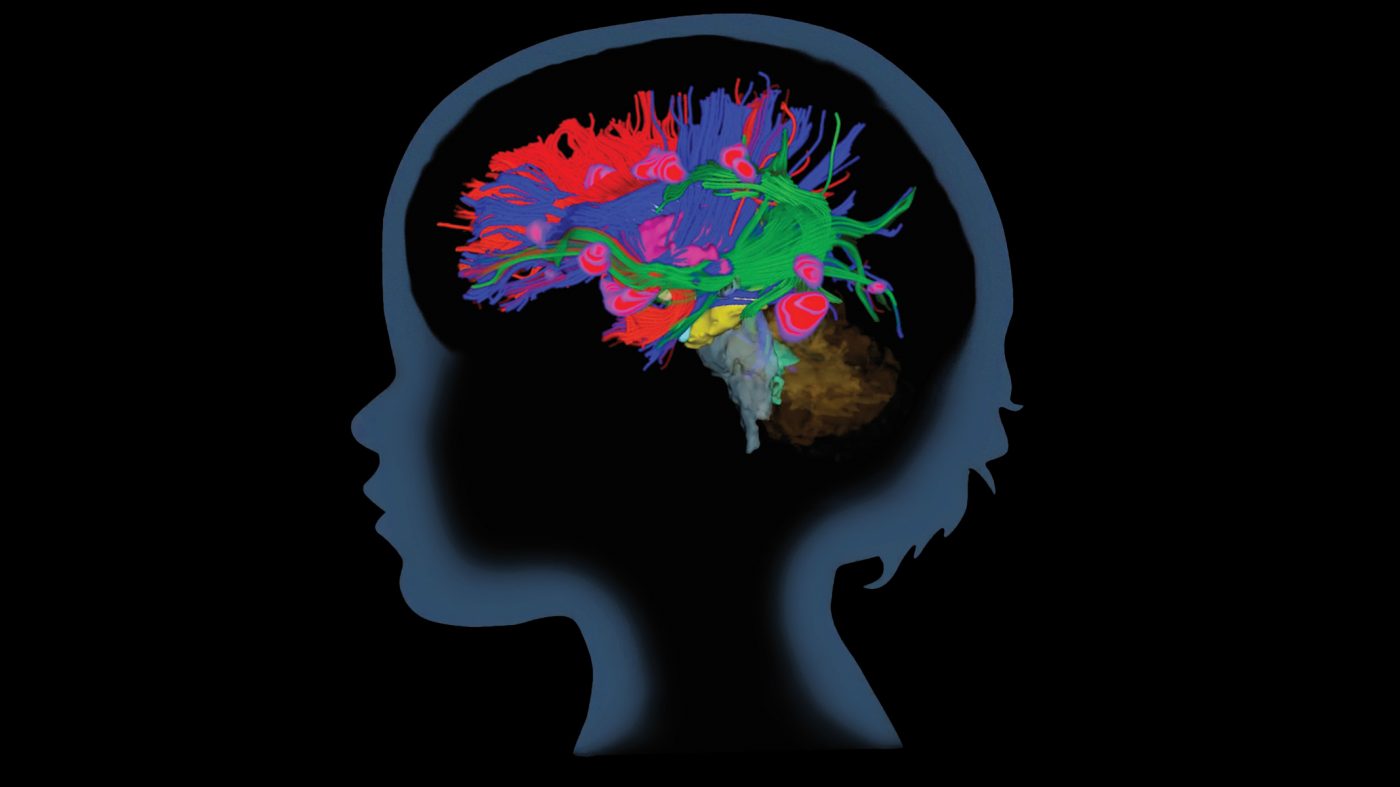

Using a magnetoencephalography (MEG) brain-imaging device—a safe, silent, noninvasive technique I-LABS has tailored for studying infants—the researchers monitored the brains of a group of 5-month-old infants during social and nonsocial interactions with an adult. The researchers then followed up with the children at 18, 21, 24, 27 and 30 months. Their findings were published in the April issue of Current Biology and represent the first such study to track the relationship between infants’ social responses and their language acquisition.

Arriving Ready for Language

Even before they produce their first words, infants are learning phonetic sound patterns. They come into the world able to pick out the human sounds that make up words in any language. Previous independent studies have shown that there is a “sensitive period” for phonetic learning between 6 months and one year when these initial universal phonetic capacities narrow down and become specific to their native languages.

“Testing the babies at 5 months was important because we were trying to establish that this social connection that lights up the baby’s brain and gets them ready to learn comes first and sets them up for when this sensitive period begins,” says Kuhl, the study’s lead author. “The social interaction is of cognitive importance and gets the baby ready for what’s coming around six months. The exaggerated face and silly-sounding speech (the ‘ensemble’) come intuitively and are the original ‘hook’ that pulls them and primes them for the learning to come.”

For the study, Kuhl says, researchers set the infants up in the MEG device and an adult female researcher engaged with the baby, speaking in parentese and reacting warmly back and forth using the tried-and-true adult-baby call and response. For the experiment’s nonsocial control, the researcher would then turn and speak to another adult seated just out of the infant’s view. The intention was to capture typical social interactions that babies experience regularly in their home environments.

The researchers’ findings showed that at 5 months, face-to-face social verbal interaction between an infant and an adult who’s sensitive to the baby’s cues significantly increases the child’s brain activity in regions involved with attention, compared with a nonsocial control. Even more exciting to those interested in babies’ language learning, the scientists found that babies’ individual levels of brain activity during the social interactions showed a strong positive association with their subsequent language skills.

“Not all children’s brains lit up to the same degree to the social ensemble,” Kuhl says. “Their social attention is different. The ones with more social attention learned language faster.”

The Joy of Face-to-Face

Kuhl says the researchers knew from previous studies that social interaction—rather than, say, watching a video or app—is essential for language learning. The current study shows that parents’ natural use of parentese, coupled with smiles, touch and their warm volley and return captures infants’ attention at an early age and makes them ready to latch onto language when that sensitive window opens around 6 months.

The researchers didn’t use the children’s parents in this study because they were concerned their history of interaction might color the babies’ responses, nor did they have the researcher turn from the baby to use a smartphone or device because they have seen in other research how upsetting that is to the babies. The researcher interacting with the babies had not met them before the experiment began but started the kind of natural interaction with them that might occur in the grocery store or when other adults drop over for a visit. She cooed back and forth with the baby, then, on cue, looked away to interact with another researcher “offstage” for a moment. On another cue, she turned back to the baby and began the social interaction again.

The babies’ little brains loved all that attention and weren’t happy (as observed by MEG’s neural light show) when they were being ignored. Some babies’ brains really sparked at the social interaction and those were the babies who, by 2-½ years, showed the greater vocabularies and more sophisticated use of language.

This doesn’t mean that babies have to be attended to at all times or they’re going to lose out on language skills, Kuhl is clear to state. No helicopter parenting here!

“That would be the wrong message to take from this research,” she says. “Part of these interactions’ special nature is that they only come occasionally. The interaction is there, then it goes away, and next time it comes, it’s like Christmas—something to be anticipated and excited about. So, parents shouldn’t stress and think, ‘Oh my gosh, here’s one more thing I have to think to do.’ Its magic is that it’s unexpected and babies are overjoyed by that.”

More Questions, More Studies

As good studies do, this one has prompted almost as many questions as it’s answered. For one thing, researchers want to know about what’s happening with the brains of babies whose mothers are dealing with clinical depression.

“In mothers who have clinical depression, you don’t see the smiles, the parentese and the warm interactions,” Kuhl says. “There are all kinds of issues with these children, one of which is a depressed affect and a slow growth of language.”

The current study also points to a greater understanding of autism and draws attention to other research, such as that of Dr. Karen Pierce of t he University of California San Diego, et al, showing that babies’ reduced attention to parentese can both contribute to downstream language and social challenges, and help diagnose toddlers with autism spectrum disorder.

“When (Pierce) tests young children who are at risk for autism (because they have a sibling with autism) with a social versus nonsocial stimulus—such as people interacting versus cars or just sound—the children with autism tend not to like social, people-oriented stuff,” Kuhl says. “And the more they tend not to, the more severe their clinical symptoms for autism are.”

Another fascinating study in the I-LABS pipeline is the differences between mothers and fathers in their deployment of parentese. Preliminary research indicates that men are talking to their babies only 25 percent of the time, compared with mothers. They do use the social ensemble to interact with babies, but ongoing research is looking at whether fathers stop using parentese earlier in the child’s development, and if they do, why that may be the case.

What’s that about? We’ll have to stay tuned.

Meanwhile, we can go ahead and indulge our impulse to engage in that silly social way with babies and know that we aren’t just forming emotional connections; we’re helping open their pathway to life with other humans.

“I suppose if you were on an island by yourself and had all the survival skills you needed to discover food, water and shelter, you might be able to survive as an isolate,” Kuhl says. “But everything we know about human beings is that we inherently crave connection with each other. And language is the gateway to any communicative connection we have. It’s our social-emotional glue.”

Authors of Infants Brain Responses to Social Interaction Predict Future Language Growth, published in the April 2024 issue of Current Biology, are Alexis N. Bosseler, Andrew N. Meltzoff, Steven Bierer, Elizabeth Huber, Julia C. Mizrahi, Eric Larson, Yaara Endevelt-Shapira, Samu Taulu and Patricia K. Kuhl. All are researchers with the University of Washington, Seattle.

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.