Dr. Angela Pyle is director of the Play Learning Lab at University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. This role puts her in an ideal situation to observe how play-based learning—as defined by the province—is playing out. Early Learning Nation magazine talked to Dr. Pyle about ways that teachers of young children can incorporate play into academics.

Swartz: How does your team determine the degree of play-based learning?

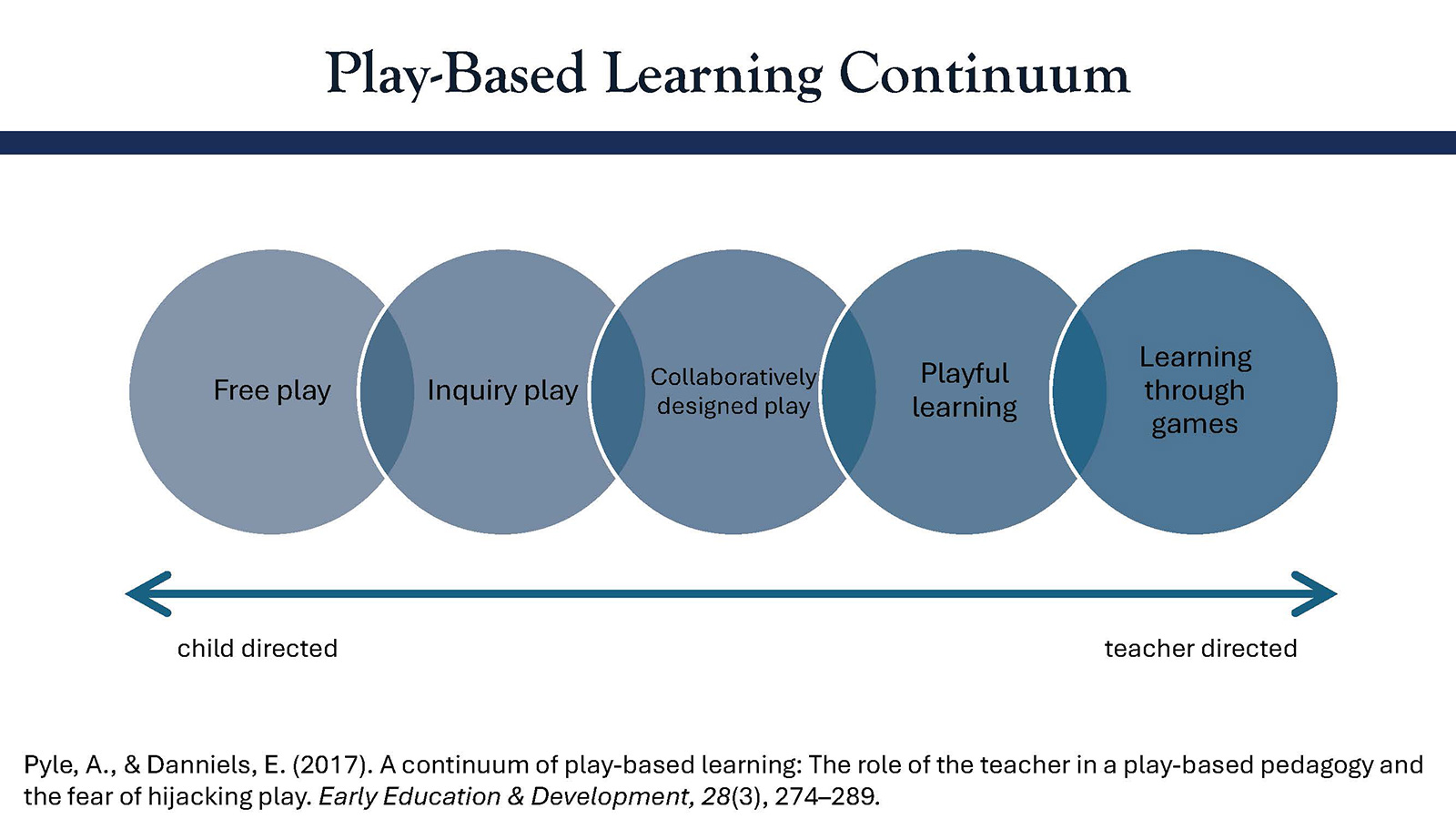

Pyle: Our Continuum of Play-Based Learning breaks down play-based learning into sub-components. Each type of play in the continuum is determined by how much agency children have and how much agency adults have. The intent behind this continuum, and all the research that we do in the lab, is really to support teachers by building on what they know and helping them do better.

Swartz: Where is the sweet spot along that continuum?

Pyle The research points to shared agency as the point where educators can make learning really meaningful and still give kids agency and excitement.

👉 Discover the Play Learning Lab’s examples of play

Swartz: How did you get into play research?

Pyle: I was a classroom teacher for several years before I went back to graduate school. I had every intention of returning to the classroom, but in 2010, as I started to do my dissertation, the Ontario government started to phase in its play-based learning model for four- and five-year-olds. Teachers were struggling with the new reality.

Swartz: What kind of challenges were they experiencing?

Pyle: We don’t have high-stakes testing like in the States, but there’s still a real accountability lens in our system when it comes to assessment and evaluation. Teachers were asking, “How do I do that when I’m supposed to do play, so I’m following their lead?” I wanted to find out where they got the message that play meant always following children’s lead. We started to unpack the reality that, actually, our curriculum is intended to be child-centered, not child-directed. We needed to understand how to help educators recognize the difference.

Swartz: What did you learn from talking to teachers?

Pyle: They all see the social-emotional value of play. They understand it’s important for young children, especially because they need to learn cooperation, good social skills, problem solving, how to communicate effectively, how to self-regulate their thoughts and emotions and reactions to things. But there’s a group of teachers who believe that the academic piece, all the other learning stuff, happens totally separately. With this group, while the kids were playing, they would be pulling kids over. They’d be like, “Come over here and I’ll do some serious teaching with you at the table.” And then they have whole group lessons where they bring everyone together and the kids just sit and listen.

Swartz: So play and learning are separated, and you’re talking about integrating them.

Pyle: Maybe I’m just being optimistic and I do prefer to live in that mindset, but I feel really positive that actually these things can still happen in the context of play.

Swartz: Some teachers already get that, right?

Pyle: Yes, there are many who align with more contemporary notions of play-based learning. They see it as a useful approach for engaging kids, giving them agency in their own learning. They see it can be used to teach academic skills as well and social-emotional skills. So they still have that free play that’s child directed, and they don’t get involved in unless they’re needed.

But then they also thoughtfully design playful contexts or games that will help. So when it comes to fundamental literacy skills, they design games to help them learn those skills—games where they look at rhyming words or alphabet games. And then they’ll thoughtfully design contexts of play where they can interact with kids and sort of scaffold kids’ learning.

Swartz: What does that look like in the classroom?

Pyle: I visited a classroom that decided to set up a pretend veterinary clinic and observed how the teacher then infused other pieces into it. So she was just like, “You know what? We should have patient charts so you can record who came in and what they needed. We should have appointment cards so they know when they’re supposed to come back.”

Swartz: You can take that in a lot of different directions.

Pyle: One day the kids were having a heated argument about whether or not the giraffe’s leg was broken. And one of the kids finally shouts, “You can’t know that because you can’t see inside.” So the educator comes in and says, “Actually, there’s a tool for that.” And another child shouts, “Oh, I know about it. It’s an X-ray, because my brother had one of those because he broke his arm.”

So then it became really exciting again, and the kids were like, “Okay. Well, we need one, obviously. To solve this giraffe mystery, we need an X-ray machine.” Of course they made it out of cardboard boxes. And then the educator points out, “You need the X-rays that are going to come out of it, so let’s look up what that looks like online and you can create your own.”

Swartz: And she worked reading into the game, too?

Pyle: Right. It’s a bit unfair to think four- and five-year-olds are going to teach themselves really hardcore difficult skills like reading and writing, but the educator incorporated books about animals, so that kids could look things up if they needed to, and she provided direct support to students using their sounds to label the x-rays they created.

Swartz: What’s next for your research?

Pyle: We’re just finishing up a project right now that looks at creating a tool for educators to help them determine how successful their play activities are, from their children’s perspectives. It’s a self-reflective tool that we designed with researchers and educators in Colombia, Bangladesh and Uganda, where there’s very limited access to education and professional development for teachers.

Swartz: Do teachers in the U.S., Canada and Europe have something to learn from the teachers in the Global South?

Pyle: Absolutely, we have a lot to learn from them. I think their creativity has to be better than ours at the moment. As I worked on this project, I had a lot of humbling moments. It’s been very useful to try and think about how we can help support educators and create resources for the majority world, where they don’t have all of these things that we think we need in every classroom.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.