Parents across the nation are struggling to access affordable and reliable child care almost five years after the start of the pandemic — a phenomenon that new survey data suggests may be worsening as stimulus funds expire.

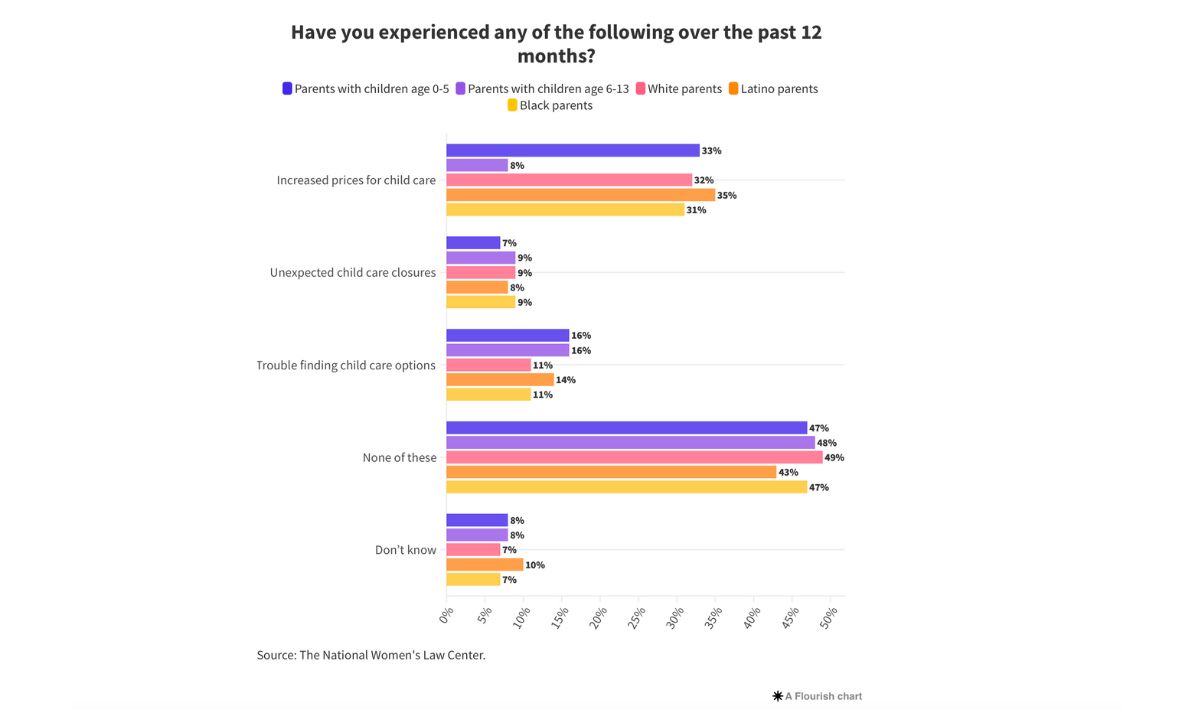

One-third of parents recently surveyed by The National Women’s Law Center reported their child care costs rose over the past year, following the expiration of the first batch of pandemic-era child care funding. Among parents of kids under age 5, that number is even higher (37%).

Just over half of parents with very young children reported dealing with at least one significant challenge with child care over the past year, including unexpected provider closures and trouble finding child care options.

“This is all a result of this decade of disinvestment,” said Melissa Boteach, the center’s vice president for Income Security and Child Care/Early Learning. “And the pandemic laid bare and exacerbated that, but ultimately to solve the problem we need not just a patchwork to help address the cliff that we’re about to drive off of, but long-term and sustained, robust public funding that actually builds a child care system that serves families and the economy.”

In reflecting on the survey results, Susan Gale Perry, CEO of Child Care Aware of America, echoed the same sentiment. “This new information is distressing,” she said, “but it’s not inconsistent with what was happening before the pandemic, and we’re all well aware that the pandemic significantly exacerbated what was already an American child care crisis.”

The expiring funds were part of the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act, a $1.9 trillion economic stimulus package, which included roughly $39 billion in direct support for child care relief.

Marking the largest investment since World War II, the funding was split into two buckets: The first $24 billion primarily went to providers to help them stay afloat during and after the COVID shutdowns and expired last September. Last week, the remaining $15 billion expired, which provided additional funding to the existing Child Care and Development Block Grant program, the primary federal grant program that allocates flexible funding to states, allowing them to provide subsidized child care to low-income families with children under 13.

This funding helped to stabilize 220,000 child care programs, impacting 10 million children and over a million families, according to a recent analysis of federal data by the National Women’s Law Center and The Center for Law and Social Policy. The organizations also found that 29% of families faced higher tuition in the month after the first expiration of funding last September, with less access to affordable care.

Last month’s Sept. 30 deadline in particular was poised to hit states’ child care systems, according to Boteach, who said, “Even in anticipation of this money expiring, some states are starting to roll back those improvements, which again means that — particularly for families eligible for a subsidy — they’re going to see anything from growing wait lists to higher co-pays to a shrinking supply, because providers aren’t getting reimbursed at the rate needed to afford to stay in business.”

Perry described this phenomenon in Nevada, where eligibility for subsidy child care programs are returning to pre-pandemic eligibility as relief funds wind down. “[This] means that families who have the least are going to need to be paying more for child care,” she said.

Across the country, she added, states were able to implement creative solutions with the help of pandemic relief funds. “The bright spots that we’re seeing are states that are continuing to pick up some of those great ideas and move forward with them using state funds. So we know we need a solution that includes a combination of federal and state and private and parent fees to really make child care work the way it needs to for this country.”

“Throughout the history of child care in this country,” Boteach added, “we have seen that when we put dollars — public dollars — into child care, it results in higher women’s workforce participation, better outcomes for children, [and] we have better economic outcomes for businesses, etc. And when we pull it away, we see the opposite.”

The latest survey was administered to better understand the ongoing impact of these expirations. It was designed by the Law Center and administered by Morning Consult between Sept. 13 and 15, reaching 4,443 adults nationally, 970 of whom are parents with children 13 years old or younger and 413 of whom have kids 5 or younger. The margin of error is plus or minus 1.5% and larger for subgroups.

Over one-third of parents surveyed reported some knowledge of the expiring funds and a majority of parents (61%) expressed concern about Monday’s deadline. Black parents were particularly impacted, with 71% reporting they are very or somewhat concerned.

A plurality of parents (42%) said that candidates running for office are not talking enough about the issue of child care.

“This is a very big-line item in families’ budgets,” Boteach said, “and if they’re not hearing from candidates about what their specific plans are, that’s a liability for those candidates.”

Despite vastly differing views about how to make parenthood more affordable in this year’s presidential race, both Vice President Kamala Harris and Republican vice president candidate JD Vance have supported an expansion of the Child Tax Credit. Harris’s economic agenda includes a proposal to raise the credit to as much as $3,600 and $6,000 in a child’s first year. Vance said he wants to raise the credit to $5,000 but opposes government spending on child care, arguing children benefit from having a parent at home with them.

Boteach noted that last month’s funding dropoff comes amid rising wages nationally for low-paid sectors. To remain competitive, child care employers would need to raise wages, even as they lose funding, saddling parents with the increased costs, she said.

Ultimately, she noted, the costs of the “broken market” of child care “are borne entirely by parents — in the form of higher fees — and providers — in the form of poverty wages.”

And often it’s women in the workforce who pay the ultimate price, she added: “Women are 90% of the early education workforce, and it’s disproportionately Black, brown and immigrant women. Women are [also] the ones who are more likely to be pushed out of the labor market when they can’t find affordable child care options.”

This article was published in partnership with The 74.

Amanda Geduld

Amanda is a Staff Reporter at The 74.