This article was published in partnership with The 74.

Young learners attending predominantly Black schools in the Charleston County School District were far more likely to face suspension and expulsion than students in the South Carolina district’s predominantly white pre-K and elementary schools, a new study shows.

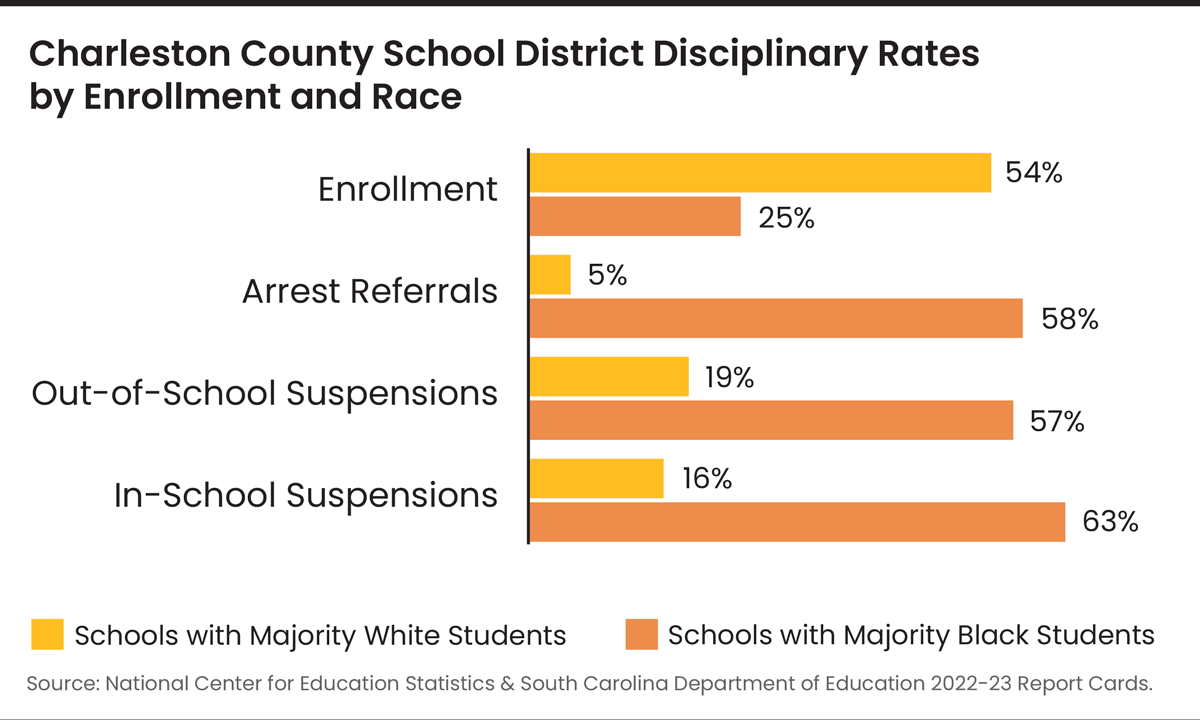

The report released by ImpactSTATS, Inc. and The BEE Collective used National Center for Education Statistics data to compare how often students were being excluded from school as a disciplinary measure at predominantly white versus Black Charleston schools in the 2022-23 school year.

To zero in on the treatment of young students, researchers considered only those schools that offered pre-kindergarten programs. Of the 42 schools in the study, 33 encompassed grades pre-K through 5; six went from pre-K to grade 8; two were pre-K to kindergarten and one school taught pre-K to second grade.

Of those schools, the ones with more than a 51% Black student population isolated children from learning settings for disciplinary reasons at a rate of 98.2 removals per 1,000 students, according to the report. This was seven times greater than the 14.1 removals per 1,000 students at majority white early-grade and elementary schools — and more than double the districtwide rate of 42.7 per 1,000 students.

Exclusionary discipline could include in-school or out-of-school suspensions and expulsion. When looking just at out-of-school suspensions in Charleston, the racial disparity by school population soared, according to the study released earlier this summer.

Students in majority Black schools faced out-of-school suspension rates of 78.8 per 1,000 students in the 2022-23 school year compared to 11.9 suspensions per 1,000 students for those in predominantly white schools.

The districtwide rate was 34.8 suspensions per 1,000 students.

“This tells us that we have a problem and it’s not children’s behavior — but adult action and adult decisions,” said lead researcher Melodie Baker.

Charleston public schools served 50,312 students at the end of the last school year: 24,978 were white, 14,291 were Black and 7,916 were Hispanic, according to the district.

Baker said removing a child from a classroom or isolating them from their teachers and peers robs them of an opportunity to learn self-regulation and is particularly damaging to the youngest learners.

“It makes kids feel like they don’t belong,” she said. “They feel ashamed. They feel confused. It affects their overall development.”

The practice is seen as harmful on many levels: Maryland, California and Connecticut are among the states that have banned or strictly limited such removals in the early grades.

Charleston County School District spokesman Andrew Pruitt last week pushed back against the study, which raises issues of racism and implicit bias, noting its data does not include the ages of the suspended students or the reasons why they were punished.

“We take any report that raises concerns about unconscious bias negatively impacting our children seriously. However, we are incredibly concerned that a specific claim of that magnitude was made in the absence of an analysis of the appropriate and relevant data,” he said in a statement.

The district didn’t start breaking down its disciplinary data by grade until recently, according to Pruitt. Though records were limited, he cited a total of 49 preschool suspensions in Charleston public schools in the 2022-23 school year. He did not separate that number by race.

Preschoolers across the U.S. are expelled at rates that are three times higher than K-12 students. South Carolina led the nation in preschool suspensions by a large margin in 2017-18 with 438 preschoolers suspended, according to the most recent available federal data.

Those numbers have grown significantly worse in the Palmetto State and were a critical focus of a state legislative hearing last week — the fourth one this year on the topic. The Joint Citizens and Legislative Committee on Children presented data showing 928 South Carolina public preschoolers received in-school and out-of-school suspensions in 2023-24; 66% of those 3- and 4-year-olds were children of color and 77% were boys.

The committee’s data for Charleston County schools, the state’s second-largest district, cites that 25 preschoolers received out-of-school suspensions in 2023-24 and fewer than five received an in-school suspension. Eighteen Black Charleston County public preschoolers received an out–of-school suspension and fewer than five white students did. Twenty-one male preschoolers received an out-of-school suspension that year and fewer than five female preschoolers did. Six preschoolers classified as special education students were among those removed from school for disciplinary reasons.

The Charleston County School District has taken steps to address systemic inequalities in discipline, Pruitt said, including professional development training for all its early education teachers that focuses on how to appropriately respond to student behavior while taking into account young learners’ social-emotional well-being. He said the district continues to work with early childhood education organizations throughout the state to adopt best practices.

The report by ImpactSTATS and The BEE Collective notes a number of studies citing the role of educator bias in harsh discipline, including perceptions of Black children as being older than they are, less innocent, more aggressive and more deserving of punishment for the same behavior displayed by white students.

New York-based ImpactSTATS was founded by Baker in 2023 to bring more diversity to the research field and to provide technical support and research assistance to grass-roots groups working with underserved communities of color.

The BEE — Beloved Early Education and Care — Collective is an advocacy group that partly funded the study and collaborated on the research. It seeks to improve maternal and child health in South Carolina’s Lowcountry, including in addressing racism and implicit bias in early child care.

Black children across all grade levels and those with disabilities have long faced higher rates of exclusionary disciplines than other student groups. According to a recent U.S. Department of Education report analyzing data from the 2020-21 school year, Black boys were nearly two times more likely than white boys to receive an out-of-school suspension or an expulsion.

“It’s mostly boys who are being suspended — mostly for rough-and-tumble play,” Baker said, speaking anecdotally of the Charleston suspensions after interviewing those who worked with or observed district students. “But there’s a lot of research out there that talks about the positives of rough-and-tumble play. Males tend to perceive that very differently.”

Of Charleston County schools’ 3,673 teachers in the 2021-22 school year, roughly 2,402 were white females, 556 were white males, 404 were Black females and 103 were Black males, according to state Education Department data.

Cara Kelly, a researcher who observed classrooms within the Charleston district for seven years, ending in 2019, recalled several instances where kindergarten children were made to sit alone and in silence for 30 minutes or more for minor infractions such as talking to other students, calling out while a teacher was speaking or standing up when they were supposed to sit for long stretches of time.

“It’s OK to give a child five minutes to calm down — but not to be completely excluded,” she said.

Kelly, now a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Oklahoma’s Early Childhood Education Institute, told The 74 she believed the punishments were not developmentally appropriate and often targeted Black children.

The report recommends the district recruit more male teachers in the early grades, increase pay for all early childhood educators, decrease student-to-staff ratios and raise awareness about discipline reform legislation that seeks to prohibit suspensions, expulsions and corporal punishment while promoting more effective means of managing student behavior.

Researchers acknowledge that the report, funded partly by the American Heart Association Voices for Healthy Kids, should be interpreted cautiously because of the data’s limitations regarding race and age.

The BEE Collective has filed a public records request asking the Charleston district to release the suspension records for children 5 and under for the last five years broken down by age, race, gender and school. Noting that the response to that Freedom of Information request is due Aug. 31, Pruitt said it was “unfortunate” that the groups moved ahead with publishing the report without that information in hand.

Tawanna R. Jennings, an infant and early childhood mental health consultant for South Carolina’s Partners for Early Attuned Relationships Network, called the study’s findings “pretty astounding,” adding she hopes the results will be shared widely and that Charleston teachers receive better training and greater support.

“There needs to be more resources so that [teachers] can understand these behaviors,” she said. “How do you teach these children and how do you be empathetic with what they may be experiencing?”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to ImpactSTATS and to The 74.