In Dan Wuori’s upcoming book he argues that America’s early childhood policy has been premised on a harmful myth: “This is the myth of daycare,” he writes, “which — in reality — simply doesn’t exist.”

How could a system millions rely on simply not exist?

Wuori’s answer: That a “crisis of misunderstanding” has turned early childhood centers into an exceedingly expensive and “industrialized form of babysitting” based on the false idea that child care is somehow separate and distinct from education. Instead, Wuori says babies learn from birth — and some research suggests even before that — and their time outside the home should be treated as schooling, not as a place for them to be watched over while their parents work.

In not embracing learning as an essential purpose, the current child care system, Wuori says, is harmful both educationally and economically for children, their parents, child care workers and society at large.

“All environments for young children are learning environments,” he said. “The question ultimately comes down to, “Is your child in a good one?”

Wuori, who espouses a “transformative” investment of public funding in early child care, began his own career in the field over three decades ago in the classroom. Teaching in an afterschool program “lit the fire” in his interest in child development and inspired him to return to graduate school.

After teaching kindergarten in South Carolina public schools for five years, he moved into school district leadership before spending 14 years as the deputy director of South Carolina’s Early Childhood Education Agency, South Carolina First Steps.

He eventually founded a public policy consultancy practice, Early Childhood Policy Solutions, focused on the needs of America’s young children and their families. Through his work, he partners with state elected leaders and advises them on early childhood policy topics.

But Wuori is perhaps best known for his social media presence on “X,” where he posts delightful videos of babies, using them to explain key child development concepts. His feed, which has amassed a prominent following, was recently described in a New York Times profile as “educational, but also, simply put — ‘awwwww.’ ”

Your baby learns to speak – not just from listening – but from watching. 👀

I’ve written many times about the keen observational powers of babies. Infants are expert observers of their parents’ faces, which (among other lessons) provide important clues as to how mom and dad… pic.twitter.com/bnH9IFwexp

— Dan Wuori (@DanWuori) September 24, 2024

Days before the official release of his book, The Daycare Myth: What We Get Wrong about Early Care and Education (and What We Should Do about It), Wuori spoke with Amanda Geduld.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Your book makes the argument that day care doesn’t exist. I think readers will hear that and say, “Well, my kid is in day care. So what do you mean that it doesn’t exist?” Can you explain what you mean?

Dan Wuori: What I mean by that is that for the better part of 100 years, we have had a policy in place — one that has really created services that are designed to support parental employment more than they are designed to support the optimal development of young children. The central thesis of the book is that we have fooled ourselves into thinking that there is this thing called day care, or child care, that is separate and distinct from education…

What we know from decades of science at this point is that that’s simply not the case. We know that young children are learning, not only from day one, but increasingly, we have this understanding that some very powerful early forms of learning actually may begin in utero. And so that’s a very different proposition, right?

… This artificial distinction between care and education is really what I’m talking about … We have conceptualized child care as almost like a holding facility, right? We’re thinking about very custodial forms of care, and that translates, in many cases, into policy. We have states that are proposing, for example, as a solution to the financial crisis that the child care industry finds itself in, deregulating in ways that sort of strip away any requirement other than those that just entail the very basic health and safety of those kids. And that is a very low bar, and, frankly, a dangerous bar, and one that frankly, we end up paying for in the long term.

You also note that the vocabulary we use matters. If we’re getting rid of the term day care, what should we be using instead?

The truth is the term day care has fallen very much out of fashion even in the field in recent years and been replaced with child care. What I would love to see is an acknowledgement that this is all either early childhood education or early care and learning. Because some acknowledgement that ultimately these are not simply holding facilities for children, [but[ that these are powerful learning laboratories, and developmental spaces, and that’s true regardless of what the sign out front says.

All environments for young children are learning environments. The question ultimately comes down to “Is your child in a good one?”

You talk also about how our current model, “Simply doesn’t work, and it doesn’t because it can’t work.” Can you explain a little bit of what you mean by that?

What I’m talking about in that section is our current economic model for child care. What we know about child care is that it is sort of like a broken, three-legged stool. We know, for example, that parents are paying more for child care in most every state at this point than they pay for in-state college tuition or for their housing costs. And so that it is unaffordable to parents in really significant ways.

We know concurrently that for the business owners themselves, this is not a profit-making venture … Providers are scarcely keeping their doors open, and the whole sad thing is sort of cobbled together on the backs of a low-income workforce that is almost exclusively female, and in many states, majority women of color, who are literally subsidizing the cost of care to families in the form of their low wages.

They are highly dependent on public assistance programs themselves, making at or near minimum wage in most states. And in fact, according to some recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, making roughly 60 cents an hour less than we pay dog walkers in this country.

The whole thing gets down to: we talk about all of those different forms of crisis that the field is in. There’s a compensation crisis, and there’s an access crisis, and there’s an affordability crisis. But the book makes the case that all of those crises are really a side effect of the fundamental crisis in the field, which is a crisis of understanding.

That we are failing to acknowledge these settings for what they truly are, and that as a result not only are we sub-optimizing this incredibly powerful window of human development, but we are saddling taxpayers … for decades to come for the result of our inaction and our failure to get things right in the early years in ways that are ultimately far more costly than doing things right in the first place.

Throughout the book, you make arguments for why we need to shift this system — for economic reasons, for educational reasons and just because it’s the right thing to do. What would a shift in this system look like, both practically on the ground and in terms of outcomes?

Yeah, I think about that question in two categories, really. The big picture message of the book is that we need transformative public investment in young children and families. I have also worked in the public policy space and with policymakers long enough to know that transformative system change very rarely happens in one fell swoop. So while making the case, for example, that early childhood development needs to be seen as a public good instead of a private market service, the book … also suggests then both some low-hanging fruit in terms of things that we could do proactively right now in ways to help improve compensation, for example, but also there’s an entire chapter that is dedicated to what I have labeled sort of forms of public policy malpractice — examples of federal and state policy where maybe with all the right intentions, the execution of our policy is actually exacerbating some of the financial crisis in the field.

… I see policymakers increasingly saying to me, “You know what I get the brain development pieces of this. I know this is important. I know we need to do better. What I don’t know is, how do we pay for it?”

And one of the major messages in the book is we are already paying for it. We’re just doing it in the dumbest possible ways. We are very much taking out, at scale, a payday loan that we are meeting our very basic immediate financial needs at the highest possible long-term cost to taxpayers … We’re paying more in terms of remediation and retention and special education throughout our K–12 system. We are paying for worse health outcomes … that could be mitigated against by doing right in the early years …

There’s an anecdote later on in the book that was recounted to you about how much some of these early child care and education teachers are struggling financially. Can you share that?

I had the good fortune two summers ago to partner with the state of Kansas on a listening tour as they were assessing the strength of their early childhood system. I traveled across the state, talking with business leaders and early childhood providers and parents, and got into a conversation with a child care provider.

We’re there, and I was asking her, “What do you need most? How could state policymakers help support you?” And she said, “Oh, well, you know, the thing that I really need the most is a floating substitute who could sort of go from classroom to classroom.”

And I said, “Oh, that makes a lot of sense. Like, somebody to help give teachers a break or use the restroom or have lunch to themselves?” And she said, “Oh no, we mostly have that covered. I’m worried that I need to give them time to get to the bank.”

… And so I said, “Oh, you know, to deposit their checks?” And she said, “Oh, no. Not that kind of bank. I can’t pay them enough to feed their families, and so I try to make time for them each week to be able to visit the local food bank.”

And boy, that just — I mean, to this day, that’s one of the most upsetting stories that has been conveyed to me in this field in my career. These women, who are literally being entrusted to help co-construct the brains of young children, are making so little that we would have to be sending them to a food bank despite their full-time employment in what I could argue is the world’s most critical profession.

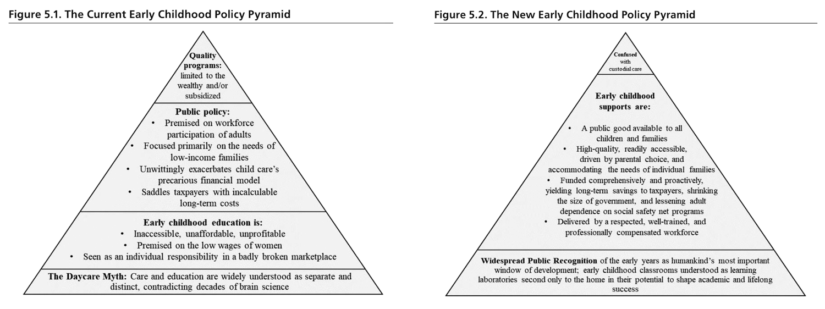

One framing motif that you use throughout the book is the food pyramid (released in 1992 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture based on what turned out to be a very flawed understanding of healthy eating). Can you explain why you chose that motif and how it reflects what’s happening in this day care myth?

I use that food pyramid example as sort of a framing around an area of public policy that we got boldly and catastrophically wrong and raise the question for readers: Where might we be doing that currently? What’s happening in our public policy that 20 years from now, we might look back at and say, “Wow. We can hardly believe we ever got something so wrong.”

And the book really makes the case that right now in our approach to young children and families we have created … this bizarro world for children that — in so many ways unexamined — is precisely the opposite of what we know from the science of early development …

One good example of that is that we know that the earliest weeks and months of life in particular play an absolutely critical role in attachment … And so then we juxtapose that against knowing that this is a country where 1-in-4 American mothers have to return to the workforce within two weeks of giving birth. And you know that in our early childhood settings we are seeing data that suggests that the teachers in those programs turn over to the tune of about 40% a year … And so during precisely the weeks and months of life that young children most need continuous, stable, nurturing relationships, we are seeing those relationships interrupted — both by a lack of paid family leave provisions and through our terrible misunderstanding of the importance of out-of-home, early childhood settings, in ways that are bound to fail us later on.

… My hope is that the book is an opportunity for us to press pause and to really rethink some of the underlying assumptions around how we have structured provisions for young children and families in this country and to come together on a bipartisan basis. One thing that I feel very strongly about — and I’m very proud of in the book — is this idea that … if ever there was an issue that really should bring us together across the partisan continuum, this ought to be it, because it makes sense for children, it makes sense for the strength of nuclear families, it makes sense in terms of our economy, it it makes sense for taxpayers … There really is something for everyone — hopefully in this conversation and hopefully in the book.

This article was published in partnership with The 74.

Amanda Geduld

Amanda is a Staff Reporter at The 74.