Chelsea Chase’s house sits on a rural road in Vermont, four miles from interstate 91. A row of cubbies filled with children’s snow boots and coats near the door, under a carport. In the background, Mt. Ascutney lies in full view from the five-acre lot that Chase and her husband bought this past September with the goal of expanding her family child care program and building a home for their family, including three kids ages 16, 11 and 7.

Downstairs, six children are snacking on pretzels and apple slices. Chase explains that they spend a lot of time outside, adding that her curriculum is nature-based and the woods and backyard pond make it ideal for the kids to explore.

For Chase, working in early childhood education is her “life’s passion for sure.” She worked as an early childhood educator for 10 years before deciding to open her own program in 2015. Chase recalls that she was working 50 to 60 hours a week when she first started, which drained her, so in 2016 she hired a staff member to help.

Her program, which serves six children ages 3 to 5 has been successful over the years. Because the demand for child care is so high in the state, she always has a waiting list, rarely has vacancies and doesn’t have to advertise. That’s why in 2024, she decided to expand her business from a registered family child care program with one classroom to a licensed facility with two. This shift would allow her to serve 12 children full time — double the number she can serve as a registered family child care provider. The process, which she kicked off this January, will take well over a year.

Chase explains her plans for the expansion. She’ll add a new room on the first floor, which will serve as a second classroom for infants and toddlers and the cubbies will move indoors. And to transition from a “registered” child care provider to a “licensed” one, she’s required to meet a number of complicated compliance regulations. She has to upgrade her septic wastewater system which will cost $55,000; deepen her well for more water storage capacity, which will cost $14,000; spend another $112,000 to expand the space; and pay an additional $6,500 to fence in the playground.

Chase is adamant that this investment only makes financial sense because of Act 76, Vermont’s landmark bill to bring near-universal child care to the state. The bill, which passed in 2023, aimed to increase access to high-quality child care and stabilize the early care and education workforce, including supporting family child care programs. Act 76 brought changes to various areas of child care and early childhood education, including significant updates to the Child Care Financial Assistance Program (CCFAP), which provides subsidy payments to providers for children from eligible families. Under CCFAP, subsidy payments vary by income and the number of children that families have in child care, but providers now get a higher rate per child than what they typically charge. Since most of the families Chase serves qualify for CCFAP, this change nearly doubles the amount of money she brings in each week for each child.

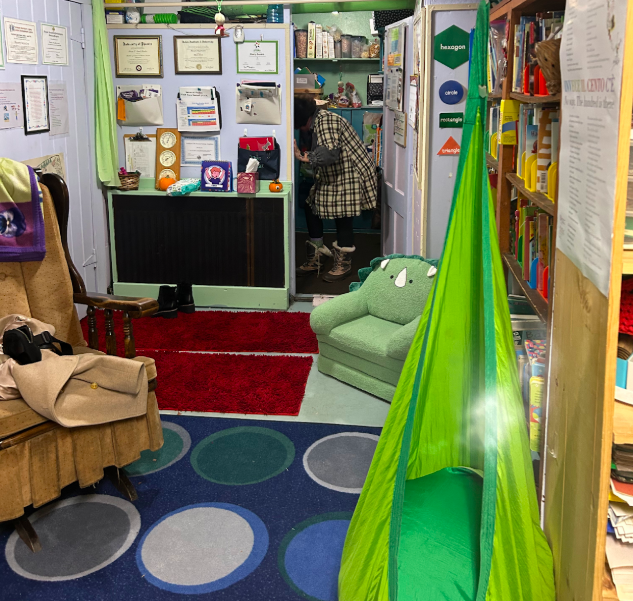

There are more than 1,000 regulated child care providers in Vermont — including family child care and center-based care providers — who could be impacted by the changes to CCFAP. One of them, Sherry Boudro, has been caring for children in the basement of her home in Windsor, Vermont for more than 30 years. Her house lends itself well to running a family child care program. It has a separate entrance to the children’s space, though it’s still connected to her main house by an internal staircase. Two fluorescent sensory swings hang from the ceiling, and the room is brightly painted and lined with bookshelves.

“Before Act 76 I was living paycheck to paycheck,” explains Boudro. Now, she has more than doubled her income. Boudro was charging families $150 per child per week; now she receives $364 per child per week — a portion of which is paid for by the state depending on each family’s financial assistance agreement. Windsor “doesn’t have a lot of high-paying jobs,” she explains, so she couldn’t charge families more money, even though she was working all the time and barely breaking even. The extra income she receives now is going toward her retirement. “I’m 60 years old and I have no retirement savings,” she says. She’s also planning to make some long-awaited repairs to the space, replacing carpets and fixing the ceiling tiles, which droop down.

Act 76 Benefits Most — But Not All — Providers

Act 76 is the “opportunity and social change of our lifetime,” says Aly Richards, CEO of Let’s Grow Kids — the advocacy organization which spearheaded the bill’s passage. Richards, who has become the state’s chief champion of the bill and de-facto expert on how to bring a near-universal child care program to a state, outlines the success of Act 76 thus far. In its first year, the legislation created 1,000 new child care slots, nearly 50 new family child care programs, over 40 child care centers and 220 new early educator jobs. And in 2024, for the first time since 2018, more child care programs opened in the state than closed.

While ACT 76 has been a game changer for many child care providers in the state, not all have received the benefits. Tammie Hazlett, for example, runs a family child care in Vermont near the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center. Most of the families she serves work have well-paying jobs at the medical center and do not qualify for subsidies, so she isn’t able to collect the higher true-cost-of-care rates. Another provider, Apryl Blake, serves two children who come from a neighboring town in New Hampshire, so they aren’t eligible, and she hasn’t asked the rest of her families to apply. “I have a problem asking them for their financial information. Not my business,” she explains.

Chase says all but one of the families she serves receives a subsidy, and the one family that doesn’t feels excluded and resentful of the process. The mother is a teacher and the father works in the tech industry. They don’t consider themselves to be well-off and they say the cost of child care is still a major expense.

For some longtime providers like Merry Ann Gilbert and Laura Butler, these changes may be coming too late. Gilbert is 59, and though her practice is winding down, she still takes care of five kids a week at her home in Milton, Vermont. She is looking to retire and spend more time with her four grandchildren but Act 76 is motivating her to stay another year or two to make additional money.

Butler, 66, who has been a family child care provider for 33 years, is also missing out — the families she serves don’t qualify for subsidies because their incomes are too high. Vermont’s support for child care has assisted Butler in other ways though, including helping her pay off the student loans she took on when she got a master’s degree.

With a 6-month-old baby sleeping in her arms, a toddler resting on a nearby couch and another toddler playing in her living room, Butler shares that she is retiring in June and moving to South Carolina with her husband so they can be closer to her family. She says she has given the families in her program notice, encouraging them to seek out other child care options.

For years, Butler worked as an advocate in the effort to professionalize the work of child care providers —- something that Vermont may be the first state to do. “When I would tell people I watched children, they’d say ‘oh you’re a babysitter,’” she says; her work wasn’t recognized as a profession, but that may soon change. In late 2023 the Vermont Association for the Education of Young Children submitted an application to the state’s Office of Professional Regulation (OPR) to make “early childhood education” a recognized profession; a recommendation by OPR has been sent to the state Legislature for review in anticipation of introducing legislation, but Butler won’t be working in the field when it comes to fruition.

Butler has no resentment though. She says she is ready for her next chapter and the warmer weather. “The next generation of providers will get the benefit,” she says. “I am satisfied that I worked hard for them.”

Rebecca Gale

Rebecca Gale is a writer with the Better Life Lab at New America where she covers child care. Follow her on Instagram at @rebeccagalewriting, and subscribe to her Substack newsletter, "It Doesn't Have to Be This Hard."