Correction appended March 27

Midway between Nashville and Atlanta, the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee, makes original use of a resource that other communities possess in abundance but fail to capitalize on: empty classrooms in public schools.

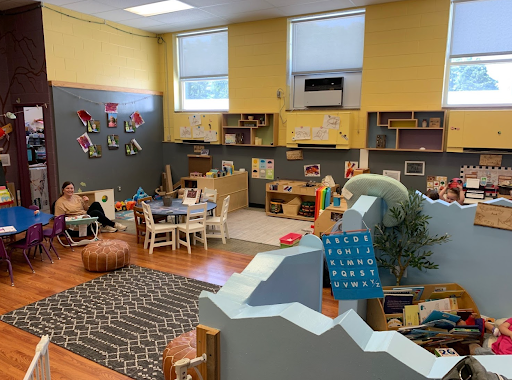

Arising two decades ago from one principal’s creative approach, micro-centers are child care centers for the children of school teachers and other staff. The city’s 12 micro-centers serve children 6 weeks old through 4 years old, when they can go to pre-kindergarten.

“It’s almost like a deconstructed child care center,” says Louise Stoney of Opportunities Exchange, a nonprofit focused on improving child care business models. Stoney says she’s working with several states that are trying to replicate the model.

Origin Story

In the early 2000s, school principal Jill Levine noticed that she was losing a lot of her bright young teachers when they had children. So she converted an empty classroom into an informal child care space.

To make sure the center was not an insurance risk, Levine reached out to the late Phil Acord of Chambliss Center for Children, a social services organization with roots in the 19th century. Acord worked with the Tennessee’s Department of Human Services, which handles licensing. The agency agreed to license these sites not as child care centers but as family child care “homes,” which has a specific legal definition. Acord also found an insurance agent to add an inexpensive rider to the schools’ existing policies.

Katie Harbison, who now runs the initiative for Chambliss, says, “We’re lucky that we’re one of the states that doesn’t have regulations that require that license to only be in a place where a person lives.” Her latest campaign involves expanding beyond schools into businesses, hospitals and other workplaces, a step that requires negotiating with state fire marshals about these nontraditional facilities.

“Licensing is rigid and unforgiving,” says Stoney. “States tend to license centers with a huge telephone book of standards, while licensing homes with this really thin folder of nothing. And micro-centers sit in between.”

Cost Savings and More

Even before the pandemic, child care programs have struggled to stay in business. Micro-centers alleviate some of the biggest pain points. The host school gives them the space for free and covers utilities, maintenance and janitorial services. Chambliss pays for teachers, technology, supplies and insurance.

“Their wages are better and their parent fees are lower,” explains Stoney, “because they’re not padded by any facilities costs or overhead cost.”

The benefits of micro-centers go beyond the financial efficiencies, Harbison explains: “Parents working in the schools can drop off their children and pay visits during lunch breaks or for nursing. And the arrangement also fosters community within the school, with staff often helping each other with pickup duties.” And since the parents are school employees, their work schedules naturally harmonize with those of their child care providers.

Best of all, micro-centers are a vital employment benefit, supporting the school system’s recruitment and retention goals.

A Nationwide Opportunity

Aaron Lowenberg and Elliot Haspel capture the dynamics around the country that make the present moment ripe for solutions such as micro-centers, writing:

“With districts looking to save costs by closing underutilized elementary school buildings yet still incurring the costs of maintaining those facilities, child care providers struggling to afford rising commercial rents, and families in dire need of more child care options, it makes sense to consider allowing child care providers to make use of these existing school buildings.”

Lowenberg and Haspel focus on Missoula, Montana, where population growth has stalled. In Chattanooga, Harbison notes, the situation is somewhat different, as the population is swelling, which leads to a shrinking pool of empty classrooms and long waitlists for infant and toddler spots.

“People are moving here for quality of life and affordability,” she says. “Some are remote workers.” When building a new school, the district tries to reserve one classroom for child care, but, increasingly, enrollment outpaces expectations. “We sometimes have to leave a school and go to another one,” she says.

Further, after weathering the pandemic with their workforce largely intact, Chambliss is now grappling with a low local unemployment rate, which means more job openings with less responsibility and higher pay.

The Network Behind Micro-Centers

Beyond economic and population fluctuations, it’s the community that fosters a project like micro-centers. “Chattanooga is known for public-private partnerships,” says Harbison. “Government, philanthropists and companies work together. We’ve had some pretty major projects through blending of public and private dollars, including redoing the waterfront and building a public aquarium.”

In particular, Harbison singles out Chattanooga 2.0, a backbone organization for the community focused on literacy and career pathways, as well as an early childhood effort called Early Matters Chattanooga that brings together 30 organizations. Chattanooga 2.0’s Smart City Venture Fund, a private social venture capital fund, helps direct local investments. She also credits the United Way of Greater Chattanooga, the Community Foundation of Greater Chattanooga and Chattanooga Chamber of Commerce.

Seeking viable workarounds. Remaining flexible. And enlisting collaborators. Every city is different, but these are the principles that generate and sustain solutions.

Correction: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the process for opening a child care center in a Tennessee school. Principal Jill Levine had permission to open a center at her school, building on a process used by another school.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.