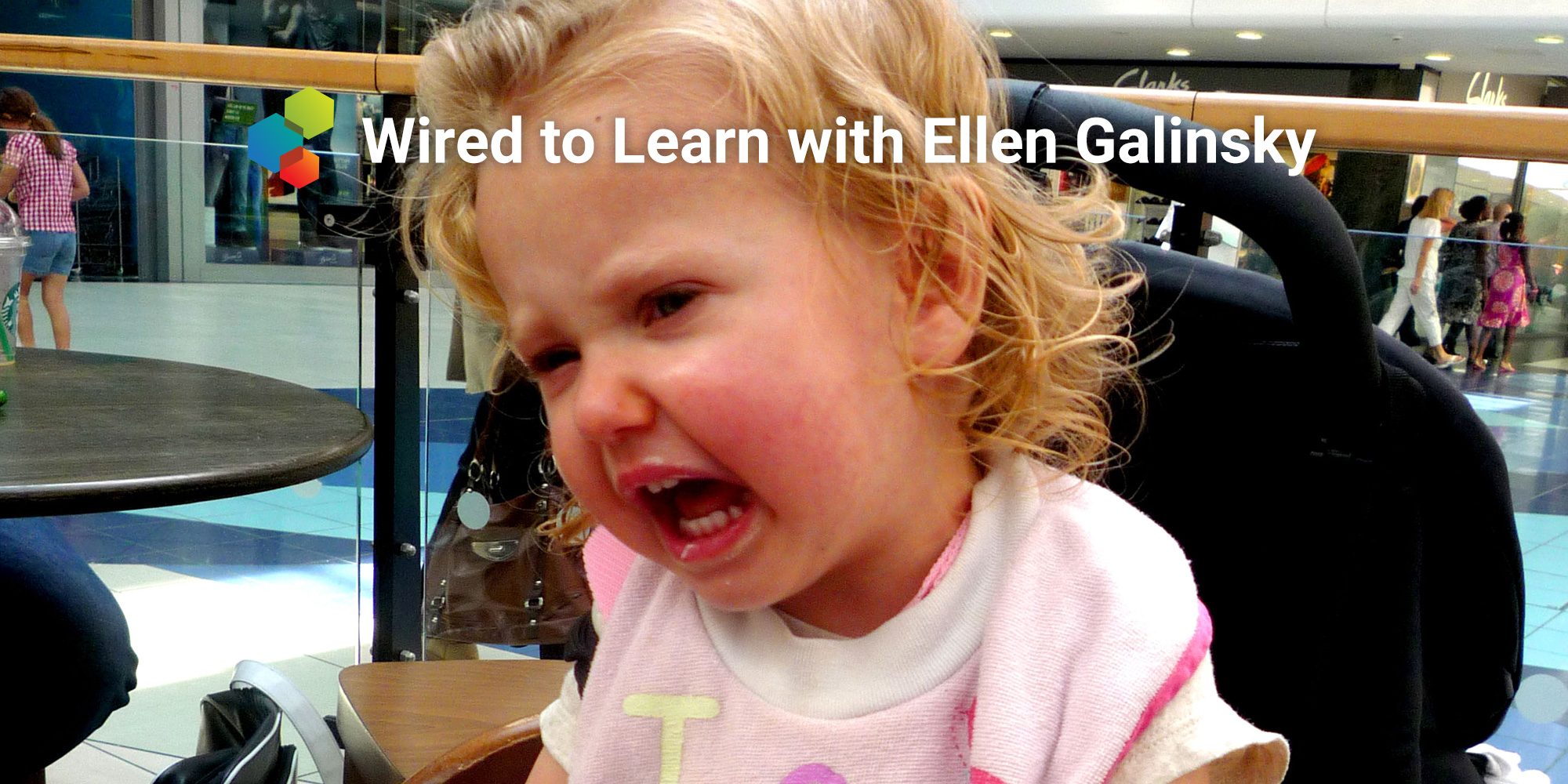

As toddlers and preschoolers begin to learn how to manage their strong feelings, sometimes their frustration, anger or sorrow overwhelms them and they kick, they push, they knock things over, they yell, they throw themselves on the floor, wailing.

Their tantrums can overwhelm us, too. It seems as if everyone nearby turns around to watch, like rubberneckers at a highway crash. And our instincts can be to match their tantrums with an equal measure of anger or severity.

If we are being our best selves, we use our own self-control to manage the intensity of our feelings. We tell them that we are not going to allow them to hurt anything and that we will hold them, take them for a walk or sit in a quiet place with them until they calm down. In other words, we give them a “pause.”

There are a few points to underscore in what I just said.

Second, you’ll notice that I didn’t use the word “time-out.” There’s understandably a lot of controversy about time-outs.

Why Use The Word Pause?

I use “pause” because a new word is needed to spell out the best —not the worst—of time-outs. As Daniel Siegel, co-author of No Drama Discipline puts it, time-outs are not effective if they punish or isolate the child.

With pauses, adults lovingly help children calm down—sometimes by removing them from the scene where the tantrum erupted—and by holding them.

They do what researchers call scaffolding. Think of a structure that is being built. As it goes up, scaffolding holds it in place until it can stand on its own. That’s what we need to do for children—help them manage their feelings until they learn to manage them on their own.

Stephanie Carlson, a researcher from the University of Minnesota who studies the development of self-control describes this transition:

Self-control begins with control from the outside in. You have parents or teachers who are telling [and showing] the child how to behave. Eventually, that control becomes internalized—it becomes driven from the child’s own desires and motivation.

What Is Self-Control?

Self-Control is an executive function skill. I know that this can sound like researcher-speak or jargon but executive function skills are critically important in helping all of us thrive. Stephanie Carlson says:

Executive function skills—in their most basic sense—refer to the brain-based skills that we need for self-control—being able to control our behavior, being able to control our emotions, and being able to control how we think.

There are many studies that show that executive function (EF) skills help us thrive. Carlson says:

There’s quite a bit of evidence now that executive function skills in early childhood predict academic achievement later on as well as school graduation, attendance, and graduation from college. And even beyond that, there are longitudinal studies showing that early executive function skills will predict physical health and even financial wellbeing later in life.

How Do We Learn Executive Function Skills, Including Self-Control?

Philip David Zelazo, also of the University of Minnesota, says that we learn EF skills by practicing them.

These are skills that you learn by doing. You can’t simply be told about EF skills and then know how to use them. I like to say that we grow our brains in particular ways by using them in particular ways. So if we want to improve our executive function skills, we need to practice these skills.

Why Is Autonomy-Supportive Caregiving A New Approach to Helping Children Learn Self-Control?

Studies have found that HOW adults help children practice these skills is important and autonomy-support is one of the best ways. Simply put, autonomy support means that we don’t fix the problems for children (control them) and we don’t stand by and do nothing (laissez-faire) but we involve the children in helping to fix problems for themselves (autonomy-supportive).

That may sound obvious, but it is far from common practice. When I give speeches, I often ask the adults in the audience to name a child’s challenging behavior like a tantrum and then write down what they would do about it. Almost everyone fixes the problem for the child, even with bribes (“if you don’t have a tantrum, I will give you a reward”) or threats (“if you do have a tantrum, no television” or “you can’t go to your friend’s birthday party”).

Autonomy support is different and much more effective. Here’s how it works.

Wait for a time after the tantrum, when things are calm and happy. Then call a family meeting to discuss tactics. You can do with children in the later toddler, in the preschool years and beyond—times when the skill of self-control is developing most rapidly.

- State the problem: When you had a tantrum the other day, you didn’t like it and neither did I.

- Involve the child in coming up with solutions: What ideas do you have that would help you stop when you start to get very upset?

- Have your child list as many ideas as he or she can think of. Write them all down.

- Evaluate each solution and whether it would work for the child and you?

- Pick one to try, write it down and post it. See if it works, and if it doesn’t, without being punitive or judgmental, have another family meeting to come up with another solution.

I know of a child who suggested a secret word. When he heard the secret word that only he and his mother knew, he would stop and calm down. It worked!

Another child typically had tantrums at transition times. She decided to come up with a Plan B—what she would do when one activity was over and it was time to move on. It worked for a while, and when it stopped working, they had another family meeting to create a new idea.

Importantly, helping children create their own idea for managing tantrums is an aspect of “pauses.” Pausing gives us a chance to stop before we act. The other benefit of pauses is to reflect on our experiences and to learn from them.

When you use pauses and autonomy supportive caregiving, you aren’t just managing tantrums‑you are giving children a skill for life!

Ellen Galinsky

Ellen Galinsky is the chief science officer at the Bezos Family Foundation where she also serves as executive director of Mind in the Making. In addition, she is a senior research advisor for the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). She also remains president of Families and Work Institute. Her life’s work revolves identifying important societal questions as they emerge, conducting research to seek answers, and turning the findings into action. She strives to be ahead of the curve, to address compelling issues, and to provide rigorous data that can affect our lives.