Praise is a funny thing. Words of acknowledgment can be the water and sunshine that help children grow into sturdy, confident and capable adults, or they can be the stifling hyperbole that sets a child up to seek approval rather than true accomplishment.

Even from an early age, it matters whether a parent says, “Whoa! You hit that ball really hard,” or “Good job! World’s Best Tee-Baller!” in response to their child’s effort.

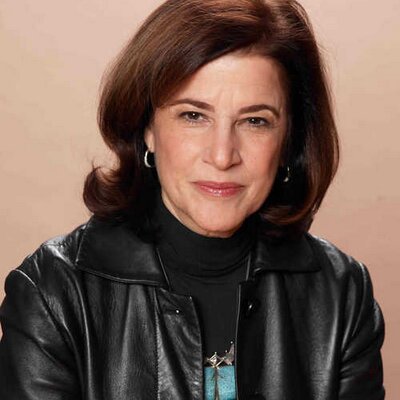

There is a lot being written about praising children these days, but some recent literature has also focused on criticizing parents, calling this “world’s-best” language, “overpraising the child” or “overparenting.” According to Ellen Galinsky, chief science officer for the Bezos Family Foundation and author of Mind in the Making: The Seven Essential Life Skills Every Child Needs, labelling parents not only doesn’t get to the heart of the matter, it diminishes the efforts of parents who almost always are trying to do what’s best for their children.

“We live in a world where it’s pretty easy to blame parents,” Galinsky says. “So, I always try to be conscious that we as parents want our children to have as good a life as possible, though we might not always go about it in the most effective way. The most important question for us as parents—or as adults in children’s lives—is to step back and ask ourselves, ‘What do we want for our children—not just right now, but years down the line?’

“I think the role of praise is that of being a facilitator, a prompter of their learning.”

An observer in any public space, anywhere in the country, will hear the Good Job! chorus resounding as parents and caregivers do their best to cheerlead children into a sense of self-worth. The problem with all the “good jobs,” Galinsky says, is that it’s become rote with repetition, an automatic response that can become meaningless to the parents and ultimately meaningless to the child.

The more serious problem with the line of praise that merely tells a child how wonderful their accomplishment is: it isn’t specific to the child’s actual efforts or strategies. Similarly, saying things like “You’re so smart! Look how smart you are!” addresses aspects of the child’s feel-like traits (being smart) and therefore provides little access to action. You’re either smart or you’re not; you’re either the best little athlete in the world or you’re not. The praise of traits and characteristics fosters the child’s desire to hang onto their smartness or cuteness or cleverness that earned the praise, rather than building an eagerness for mastery, a drive to keep taking on new challenges.

“There has been a lot of emphasis in recent years in building a child’s self-esteem and resiliency,” she says. “But I want to see us go a step beyond that. Remember those little figures that, no matter what you did, they would always pop back up? (Weebles wobble but they don’t fall down!” Who could forget?)

“Well, all that bouncing back and bouncing up again really isn’t taking anyone forward. I’m interested in kids who take the next step forward, who try harder. The challenges we encounter in life aren’t predictable—I mean, look at this pandemic year—and we want kids who can take on those challenges.”

In considering the relationship of praise to a child’s development, Galinsky points to the groundbreaking work of Dr. Carol S. Dweck, author of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, whose decades-long work on mindsets and motivation has distinguished the types of feedback that can encourage a child to seek challenge and pursue accomplishment, or to seek praise and look for the easy way out.

“Carol Dweck started doing her work during the whole self-esteem movement in the 1990s. She told me that at that time, the self-esteem gurus were telling parents and teachers, ‘You must praise your child at every opportunity. Tell them how talented and brilliant they are. This is going to give them confidence and motivation.’ Dweck was actually interested in students’ attitudes toward failure. She asked the question, ‘Who are the children who wilt in the face of challenge?’” From that seminal question and many studies, Dweck coined the terms “fixed mindset” and “growth mindset” to describe why some students were devastated by even modest setbacks and some would persevere when challenged.

As it turns out, telling a child “You’re so beautiful. You’re so smart. You’re such a good athlete” actually had the opposite effect from what was intended. Rather than building self-esteem, it created a fear of risking the inevitable mistakes humans make when they’re learning something new. The child digs in and hangs on, developing a fixed mindset that resists risk, which is a part of all learning.

Parental hyperbole can actually increase a child’s insecurity—and may reflect their own. The parent may be afraid that the day their child stops being amazing, they’re toast. That’s a lot of freight for tiny shoulders. The grandiosity can also make cynics of children who have keen built-in baloney detectors and know Grandma is making stuff up when she says they’re the genius of all geniuses. What else is she being insincere about?

Sometimes a parent’s endless praise can also push the child away from what started out being a pleasurable activity. The child is painting and just wants to keep exploring with textures and colors, but suddenly Mom is telling everyone what a brilliant artist she is and showing everyone who walks in the house the amazing pictures the child has created. The kid just wants to see if mixing yellow and blue together actually will make green and suddenly, it’s all performance art and zero fun.

Galinsky says this doesn’t mean that parents shouldn’t say anything or that caregivers should ignore achievement.

“Children want to learn. They want to explore, and we don’t need to step completely out of the way, but we need to see if we can help them figure out what they did and what they’ve learned from it. How can they do it again? Let them do things for themselves and ask questions about their strategy. ‘You worked really hard to figure out what happened when you mixed colors together. What did you do to get that new color?’ underscores their agency in a way that ‘You tried so hard’ really doesn’t.

“Prompting them to consider how they accomplished something helps keep the fire for learning burning in children’s eyes,” she says. “When we look at newborns and try to figure out what they’re learning, we (researchers) notice what they’re looking at. When they’ve had enough, they move on to something new. Children explore. They don’t need to be taught to be creative or rewarded for their explorations. The learning is the reward.”

And that, she says, is the difference between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic reward. Babies who are encouraged to maintain their own motivation will usually stay self-motivated, lifetime learners as they go through life. Little ones who get a reward for solving a puzzle, for example, may then want to be rewarded as they get older.

“There are endless books about the number of kids in college who are struggling. Some of them may have gone from a life where they were always praised for being wonderful and they were used to having people fix problems for them, rather than helping them learn to fix things for themselves. Suddenly, there may be no one around at college who’s going to do that for them, and they can feel very lost.”

It’s important to remember that none of the habits we as parents and caregivers have picked up are set in stone. Advances in neuroscience have revealed just how plastic and malleable even adult brains are and how all of us can learn new ways of doing things. For big people as well as little ones, mindsets can change and an orientation for growth can become just as much a part of the wiring as those less-effective approaches have been. As is evident on every page of Mind in the Making, Galinsky is a major cheerleader for those who are doing their best to raise healthy, well-rounded children.

She’s just not likely to be yelling, “Good JOB!” from the sidelines.

RESOURCES

- Mind in the Making: The Seven Essential Life Skills Every Child Needs, by Ellen Galinsky

- Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, by Carol S. Dweck

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.