Deborah VanderGaast originally started running a child care business out of her home in Tipton, Iowa in 2005 serving children with special needs when her own child had healthcare needs. But then in 2012 she bought an abandoned commercial building and worked to turn it into a center. She opened half of it at first, thinking it would take a while to reach 30 children. It only took five months. So her family took out loans to finish the rest of the building and serve 75 children. In early 2019 her enrollment averaged about 70 children and she was “doing pretty good,” she said. But then the local school district opened up new universal preschool spots, which siphoned off four-year-olds, who are far less expensive to care for and help subsidize infants and younger children.

The pandemic actually offered her some relief for a bit: the streams of state and federal relief funding helped keep her afloat. “The pandemic kind of saved us from closing sooner,” she said. With fewer children to serve and less staff, she was able to break even.

But as families began to return she started to face the same crisis that’s confronted every provider across the country: a severe staffing shortage. In normal times, she would have 30 employees, with five stable lead staff and turnover among the others. “After the pandemic I just simply wasn’t hiring people,” she said. She estimates that at most she’s had two job applicants in the last year, one of whom couldn’t pass the required background check. She faced “chronic low staffing and high stress,” she said. She has only averaged 30 children at a time because she can’t hold onto enough employees to enroll more. She briefly reopened her infant room, only to have to shut it down because of unreliable staff.

By the beginning of this year, she knew that, if there wasn’t more government funding on its way, she would have to close. “There was always hope that help was coming,” she said. She decided that, with what she had saved, she could only make it to December without more funding before she would have to declare bankruptcy. But money never arrived, particularly after Democrats’ Build Back Better package that would have included historic investment in child care failed. “There was no help,” she said.

She closed her doors at the end of the summer to give her families and staff time to find other things.

There aren’t any other in-home child care businesses to absorb all of her families. “There were four registered daycares in this zip code. Now there’s two,” she said. “I was still getting calls for care even after I closed.” A family with a child who had behavioral issues called her asking if she knew a center that would take them. “I said, ‘No, sorry, I was the only one.’” She knows other centers in her area who are struggling to stay open, too.

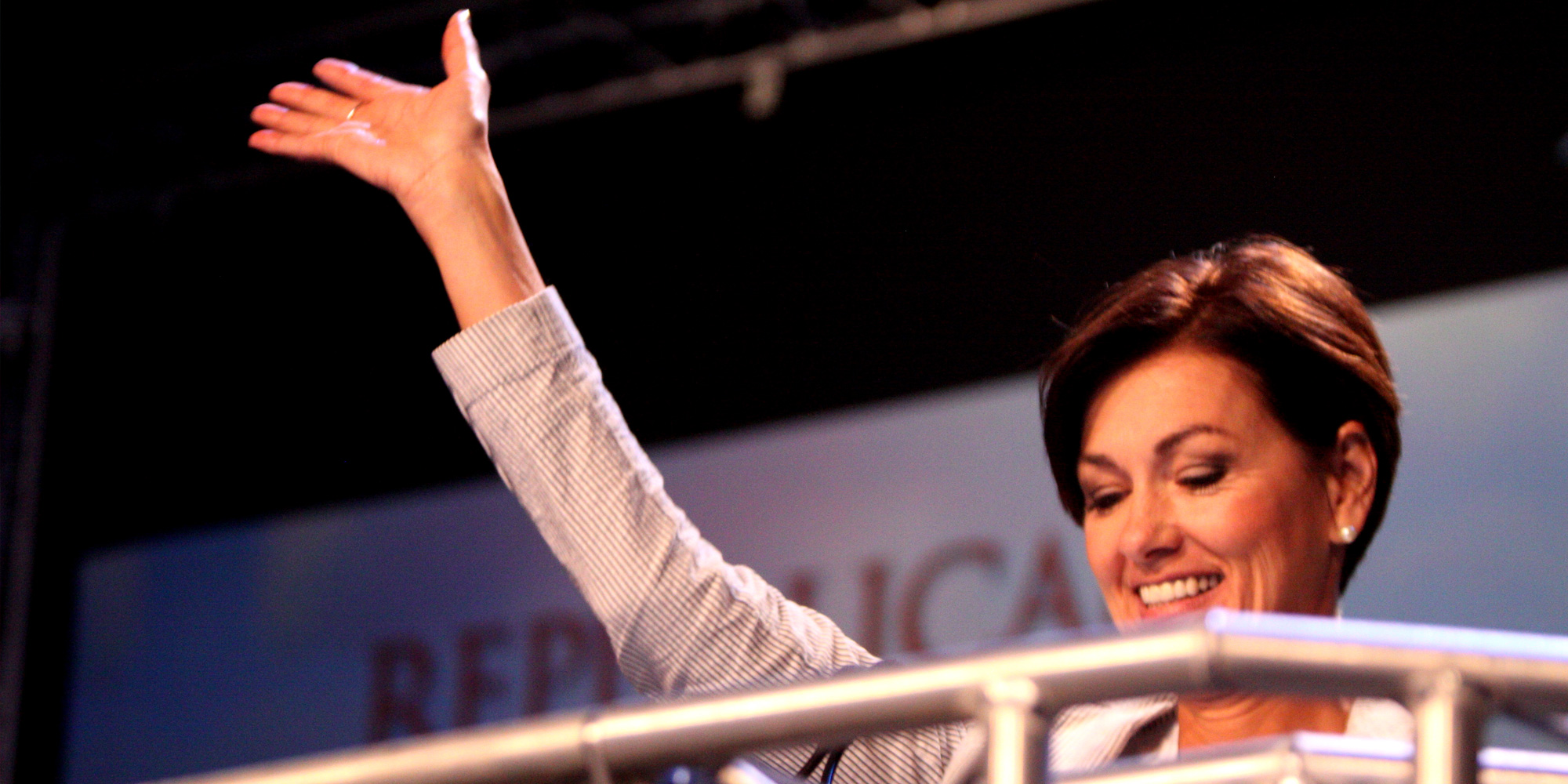

Amid such an acute crisis facing Iowa’s child care and early education providers, one might think that the state’s governor would pursue every pot of money available to keep the sector afloat and ensure that families have the care they need. But Republican Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds has recently done the opposite. Despite the fact that her state was eligible to apply for the federal government’s Preschool Development Grants Birth Through Five program, and staff had been working on the application materials, she refused to send in an application to pursue the money, forfeiting the state’s chance at receiving it.

The decision took child care providers and advocates in the state by surprise. Sheila Hansen, senior policy advocate and government relations manager at Common Good Iowa, is on a steering committee for early childhood in the state that was getting regular updates on the process. “There was never any concern, there wasn’t anything not on track,” she said. “I hadn’t received any indication that things were off at all.”

“It was purely political, the governor’s decision—we’re not taking money from Biden,” VanderGaast said. “It certainly had nothing to do with the needs of Iowa or our actual situation.”

The governor’s office did not respond to a question from Early Learning Nation about why she decided not to apply for the funding, nor did they share the state’s application materials. The Des Moines Register reported that the governor objected to having to put $3 million of the state’s resources toward receiving the $30 million from the federal government, although Democratic State Senator Claire Celsi told the paper that the state was unable to review the paperwork to submit it on time. As part of the application process, states have to submit a letter on the governor’s letterhead saying which agency will administer the grant, but Reynolds didn’t provide the letter.

“I’m holding Gov. Reynolds responsible for this,” Celsi told the paper. “She could not have kicked our child care providers in the teeth any worse than she did here by not really digging in and doing the work necessary to secure this grant.”

It’s been difficult even for people in the state to find out exactly what happened and why. “They sort of put a gag order on things,” Hansen said. “It’s become that kind of an issue where staff aren’t allowed to talk about it to anybody.” She said her organization has been given a variety of reasons why the governor didn’t submit the application. One was an objection to the state being required to spend $3 million of its own money, but it has a budget surplus of over $1 billion. “It’s not as if the $3 million would have been hard to come up with,” Hansen said. Another reason that’s been offered, Hansen said, was that staff didn’t have enough time to sign off on the application, even though everyone had been working on it for months. “Everything had been, as far as everyone knew, going on time and following the timeline and was going as expected,” Hansen said. A third reason is that the state still has unspent federal funding for child care from the American Rescue Act and could put that toward the things that the grant would have covered. “We’re like, ‘Okay, let’s do that, let’s see it,’” Hansen said. But they haven’t seen any plans to follow through. That would also mean that American Rescue Plan funding couldn’t be used for other purposes.

Common Good Iowa has been trying to get a copy of the grant application but hasn’t been able to, and staff aren’t answering their questions about it. But Hansen knew that the money, had the state received it, would have gone to increasing compensation for child care providers—“which was huge,” she said—as well as supporting infants and children’s mental health and creating more preschool spots.

“This is $30 million that Iowa could have used,” Hansen said. The state has done needs assessments to identify gaps in child care and early education services, and the grant money was meant to plug those holes. Without it, “that just means that there’s continual need out there,” she said. Just as with other states, hers has a shortage of child care employees and centers because the wages and benefits are so low. There’s a Wendy’s near where she lives offering a starting wage of $16 per hour. “When your average wage is anywhere between $10 and $12, if even that, why not go to Wendy’s?” she said. The state has focused on spending a lot of its money on building physical infrastructure, such as new buildings, for child care, but less has gone toward supporting the workers in those buildings. A new center just opened in Hansen’s hometown with lots of state support, she said. But it has 100 openings, despite a waitlist of well over 100 children, because the owner can’t find enough staff to watch the children. “We don’t need another building,” Hansen said. “We need the bodies. The only way we can do that is to start to pay them more.”

Preschool Development Grants have been awarded to states since 2018, when the first ones were doled out. They are typically used for things like assessing the need for early care and preschool, strategic planning, building systems and programming, and improving quality. But they can also be used to increase workforce compensation—a key demand from providers who are struggling to retain staff—and support direct services for young children. States that receive the grants are required to spend their own money as well, no less than 30 percent of the federal grant amount, similar to other education programs. “It’s going to take investments from everywhere to continue to make the child care system successful,” noted Anne Hedgepeth, chief of policy & advocacy at ChildCare Aware of America.

Iowa has received this grant before, and it applied for another in late 2019, intending to use the money for a needs assessment, strategic planning and investing in the workforce through professional development training, although it ultimately wasn’t awarded the money. For this round, Hedgepeth said, the Department of Health and Human Services has told states that it wants to see them use the money to support the workforce through compensation, credentialing such as licensure and degrees, and other supports. But the money is also important for setting up systems that make it easier for new providers to open, for staff to get connected to all the trainings and background checks they need to pass to start working, and for families to easily find nearby options.

“Federal funding was available, and Iowa is leaving that funding on the table,” Hedgepeth said. There was no guarantee that the state would be awarded the money, although there were 25 eligible states for 24 potential awards so it was more probable than ever, and federal officials had recently told states that qualified applicants were likely to be approved. “They were eligible and they aren’t even going to take this step. That’s disappointing,” she said.

VanderGaast hasn’t completely extricated herself from the child care sector yet. First there’s the fact that she is struggling to sell her building, so she still has to make the payments. She ran for office this year and, while she lost, plans to stay involved and potentially run again so that she can pass legislation better supporting the sector. Recently she’s been interviewing for jobs, including one as a child care nurse consultant given that she was a nurse before she opened up her center. “I’m interviewing for jobs now that will…pay twice as much,” she said.

Bryce Covert

Bryce Covert is an independent journalist writing about the economy. She is a contributing op-ed writer at the New York Times and a contributing writer at The Nation. Her writing has appeared in Time Magazine, the Washington Post, New York Magazine, the New Republic, Slate, and others, and she won a 2016 Exceptional Merit in Media Award from the National Women’s Political Caucus. She has appeared on ABC, CBS, MSNBC, NPR, and other outlets. She was previously Economic Editor at ThinkProgress, Editor of the Roosevelt Institute’s Next New Deal blog, and a contributor at Forbes. She also worked as a financial reporter and head of the energy sector at mergermarket, an online newswire that is part of the Financial Times group.