Just as Early Learning Nation magazine showcases the ways families, researchers and grassroots nonprofits and organizations are building an early learning nation—one community at a time—our Community Cultivators series highlights how innovators across all sectors build and sustain global communities from the ground up. We hope the series inspires your own early childhood work.

The possibilities are unlimited for the children of single mothers. Just ask President Barack Obama. Vice President Kamala Harris. Ford Foundation president Darren Walker. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. Entrepreneur and Pittsburgh Steelers owner Thomas Tull. Comedians like Jon Stewart and Eddie Murphy, performers like Jay-Z and Mariah Carey, athletes like LeBron James, Hope Solo and Alex Rodriguez.

Single mothers brought up all these luminaries, but it’s probably a mistake to assume they did it all by themselves. They had relatives, friends, neighbors—in other words, a village—to parent these future all-stars.

About 22% of U.S. children live with single mothers, and while all of them have great potential, it’s no secret that these families face great challenges, too. Founded in 1993, the Jeremiah Program (JP) forges connections among single mothers in nine cities and energizes them individually and collectively. JP President and CEO Chastity Lord joined JP at a critical moment, just six months before the pandemic hit.

“Chastity’s remarkable personal journey and visionary leadership are what JP needed to drive transformative change,” says Ethelind Kaba, executive director of the Ann Bancroft Foundation and secretary of the JP National Governing Board (and inaugural JP Alumni Fellow). “She inspires me and the other JP moms to wield power in our personal stories on our own journeys to self-sufficiency.”

Early Learning Nation magazine caught up with Lord and learned a few things about the resilience, dignity and ambitions of America’s single mothers and the ways to make it safer for them to bet on themselves.

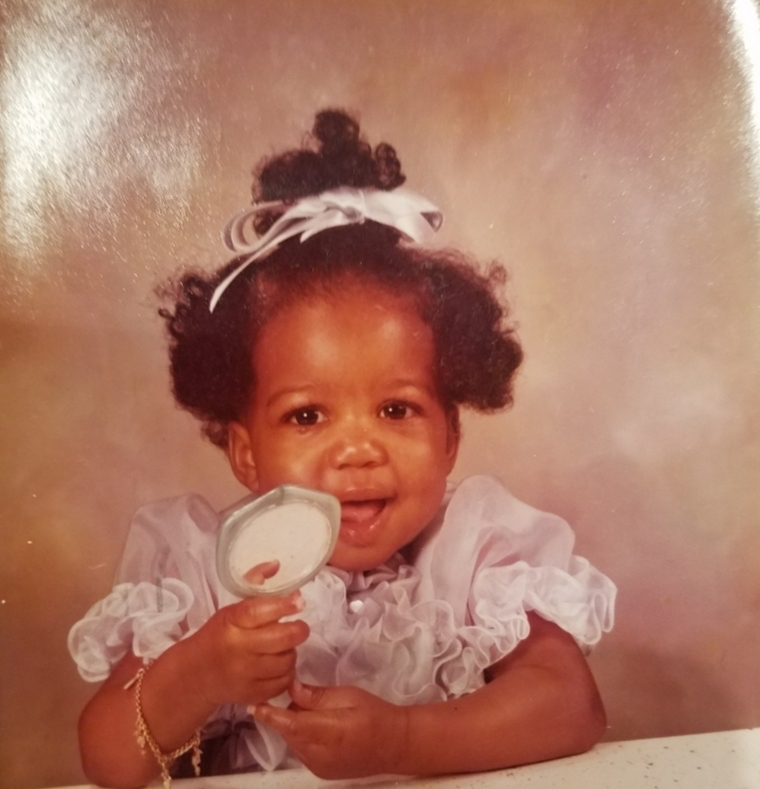

• Experience counts. Besides LeBron, Obama and A-Rod, you know who else was brought up by a single mom? Chastity Lord. “I would’ve been a JP kid,” she acknowledges. “My mom would’ve been a JP mom, and that’s why I say to our moms, ‘I am your child. I am proof of what can happen in a generation.’” Her leadership of JP draws upon her personal story and the travails and triumphs of her own single mother. “I know what it means to be housing unstable,” she says. “I know what it means to be without. We were nomadic, which is just a euphemism for being poor. I benefited from Section 8 [housing], reduced lunch, arts in schools, Pell Grants and Perkins [student] Loans.”

JP encourages beneficiaries of public programs to advocate for more robust investments and for colleges to do more to make higher education affordable. For American mothers living in poverty, Lord observes, the point in life when they’re the most economically vulnerable coincides with the most vulnerable moment in their children’s lives. The same dilemma that threatens to hold them back is what makes them so effective in their advocacy, whether it’s in front of policymakers or in the workplace.

She urges single moms to bring their full identities into every situation. That means she can call in sick when her baby’s sick. It means she can tell a story about something her child said without being afraid of her supervisor’s prying questions or assumptions about her commitment to the job.

• Come together. JP works best when moms of different talents and abilities, and from different backgrounds, share their visions and aspirations. Lord compares the effect to the Transformers—the toy, the movie, etc., whose slogan is “More Than Meets the Eye.” They come apart and reassemble themselves into new shapes, with new powers.

JP actively engages with 66% of its alumni, adding up to a large and growing nationwide community. Last March, the organization held its first in-person summit in Austin, Texas, with 300 single moms and alumni in attendance. “There’s something beautiful and healing about being in a room of other people with that shared experience,” Lord says. “We intentionally set out to extend this sisterhood to make it beneficial for the space, the industry and, ultimately, for the people we serve.”

• Seize the moment. The pandemic was especially devastating for the population served by JP. According to one study, “the challenges that single parents faced prior to the pandemic generally magnified after the arrival of COVID-19. In April 2020, one in four single parents was unemployed, and unemployment rates recovered more slowly for single parents throughout 2021.”

Lord recalls urging her board to act swiftly and boldly. “We can’t tread water,” she wrote in an email, “because there is no water.” Switching to a hockey metaphor, she told them: “We can skate to where the puck is, we can skate to where the puck is going—or, better still, we can try to influence the direction of the puck.”

Lord’s first priority was retaining staff and operations across the country, including five child development centers. Beyond that, she recognized that the disruption presented an historic opportunity to address policies and systems in ways that wouldn’t have been possible previously. That determination persists in the post-pandemic era, especially around the issues that the mothers in the network care most about: the criminal justice system, early childhood education and career opportunities.

• Money matters. Society often judges single moms for poor financial choices when the reality is that expenses often pile up due to factors beyond their control—even when (or especially when) they’re trying to improve their lives.

Stable housing is the foundation of making a home, but the financial obstacles are often insurmountable. “Try and come up with first month’s rent, last month’s rent and security deposit when you are living paycheck to paycheck,” she says. “If you’re lucky enough to have emergency money in the bank, that’s going right to the landlord, and then you don’t have emergency money anymore.”

On the subject of higher education, a well-known pathway out of poverty, Lord says many colleges still haven’t made commonsense adjustments to welcome students who happen to have young children. “Their financial aid award letters include housing, transportation, books,” she notes. “But you know what it doesn’t have? It doesn’t have child care, which is one of the biggest chunks of a single mom’s budget.” Lord commends Daria J. Willis at Howard Community College in Maryland for creating a student- parent section of the library.

• It takes two (generations). “You can’t talk about generational poverty in this country without talking about gender and race,” asserts Lord, who sees the wisdom of the two-generation approach and has experienced it firsthand.

Efforts to improve the lives of American women are bound to fail if they leave motherhood out of the equation. “We lose a generation when we don’t think of them as a unit,” she says. A national advisor of the Aspen Ascend Postsecondary Success initiative, she praises the Aspen Institute for “creating the space to facilitate conversations around centering the complete identity of a family unit and says it has brought her into a circle with other Black female leaders—including Michelle Rhone Collins (LIFT), Aisha Nyandoro (Springboard To Opportunities) and Nicole Lynn Lewis (Generation Hope). “I sit here because of people who are willing to be in community,” she says. “It takes a constellation of stars—not a supernova.”

Although she never forgets about the systemic challenges that exist for single mothers, the possibilities for remaking those systems give her energy. “It’s an incredible opportunity,” she says, “waking up every morning, thinking about how to reimagine the whole framework for making our network more powerful.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.