Terri Simms has run her child care business, known as Playtime Nursery School, in Dayton, Ohio for over 27 years. She was forced to shut down for three months in the early days of the pandemic for safety reasons, but today she’s shutting her program down for the day out of protest.

In the early days her business was sustainable and Simms was able to pay her teachers reasonably well. Then in about 2009, Ohio started steadily reducing reimbursement rates for families who get subsidies, and increased quality rating requirements. Today the state has the country’s lowest reimbursement formula. It also pays providers based on attendance, not enrollment, which means that if a kid is out sick she loses money despite keeping the spot open for that family. Simms only has one family that pays completely out of pocket; nearly all of her other children receive government subsidies.

“I’m working now in the negative,” Simms said. It costs her somewhere between $470 to $500 a week to care for an infant, but she’s only reimbursed $375 by the state. “That’s not no money,” she said. But her parents can’t make up the difference, so she has to take it out of her teachers’ pay. “I’ve got some dedicated, loving, caring, outstanding teachers who come to work every day,” she said. “I can’t pay my teachers what they’re worth.”

That changed briefly after the American Rescue Plan was passed, which spent $39 billion on propping up the struggling child care sector, the single largest amount of funding the industry has ever received. Simms used the money she received to give her teachers bonuses knowing that it would someday run out. Run out it did—the money stopped flowing to states this past September. Simms’s bonuses are no more. One of her teacher’s electricity recently got turned off because she couldn’t afford to pay the bill. Another had to move houses into something less expensive because she couldn’t afford where she was living.

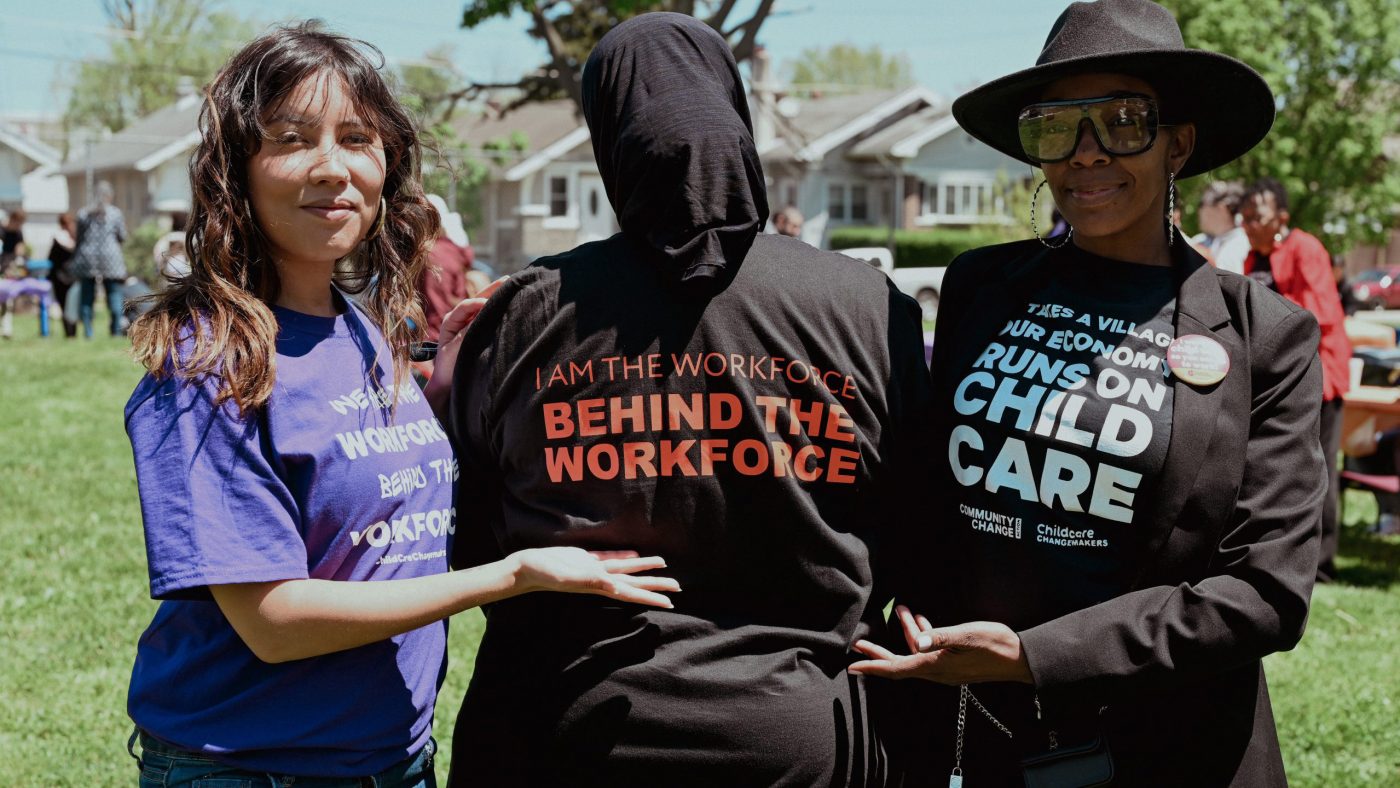

That’s why on May 13—today—she’s joining 1,080 other child care providers across the country who will be closing their doors and calling out to demand more funding for child care. They’re taking part in the third annual Day Without Child Care, and this year a record-breaking number of providers are shutting down. The event comes after the so-called “child care cliff,” when federal pandemic relief money for the sector has almost completely dried up. In a January survey, over half of providers knew of at least one program that had closed in their community over the previous six months, and about half said they had to increase tuition.

Providers who close down today will hold 84 events across 26 states to demand the government pay them better, make care more affordable for families, include gender and racial justice in the system, and expand the Child Tax Credit. That last demand is new this year and inspired by the experience of 2021, when the government increased the amount of the benefit and gave it to more families, cutting the child poverty rate in half. Expanding it again “would help us build a solid foundation for all of our children who all deserve an equal opportunity to thrive,” Dorian Warren, co-president of Community Change, which is organizing the Day Without Child Care, said on a press call last week.

The day of action will also focus on Republican lawmakers who have refused to pass more child care funding; along with two conservative Democratic members of congress, who stood in lockstep against President Biden’s Build Back Better legislative package that had historic investments in child care. Republican’s refusal to pass more funding for the sector is “pushing our system to the brink of collapse once again,” Warren said. “Time is running out.”

The lapse in federal funding, without anything else coming now that it’s gone, has put many child care providers in a bind. Johnny Anderson, who owns the largest family-owned child care company in Utah and shut down all of his 16 centers on Monday, said his state required providers to pay teachers at least $15 an hour when they got relief money. “We were obviously happy to do it, because we wanted to pay teachers more, and the grant gave us the ability to afford that,” he said on the press call. But that money will run out entirely at the end of the summer. Without more government funding, providers like him can only maintain that level of pay for teachers by raising prices for families, who are already struggling to afford care. “It’s a recipe for disaster,” he said. The result, he said, is providers forced to close their doors permanently.

Some states have stepped up to shield child care providers from the cliff, finding their own sources of funding to fill the gaps. In those states, there was barely any increase in how many parents lost access to child care, compared to nearly a quarter in states that didn’t provide their own funds. Utah is one of those that hasn’t put more money into the sector. “Utah’s a conservative state,” Anderson noted. “We have been unsuccessful.”

“Shutting down on the Day Without Child Care is a glimpse of the permanent closures that might happen in our communities if we don’t take action,” Warren said. “We know our system is in crisis and we also know it does not have to be this way.”

This is the first year that Simms will be shutting her program down as part of the Day Without Child Care. “I decided to shut down for the same reason that Rosa Parks refused to stand up. Enough is enough,” she said. “I’m a business. Pay me what I’m worth.” Her teachers and parents are completely behind her, she said, and they’ll be going with her to the capitol for a protest as part of the day’s actions.

One of the people she serves is Rose Elheazy. Last year Elheazy got a call from her grandchildren’s other grandmother saying her daughter had died and her grandchildren—ages 18 months, four, eight and 12—were in custody of the state. She needed someone to take them so they could go to their mother’s funeral. Eventually it turned out that no one could take the children in full time, and Elheazy made the difficult decision to take them in herself so they could be close to family members.

Her decision came with a lot of hardship. At first she didn’t get any public benefits to help care for the kids, and Elheazy can’t work due to a shoulder injury she sustained on the job four years ago. She had been living on workers comp payments and taking care of her elderly mother 24 hours a day, seven days a week while also going to physical therapy appointments for her shoulder. She didn’t have enough resources to feed the kids, let alone the time to care for the ones too young for school during the day. She was in a “really bad, broken situation,” she said.

Then she got in touch with Simms, who connected her to a state program that allowed Elheazy to send the two youngest to Playtime Nursery School for free. “I didn’t always have breakfast,” Elheazy said, but “I knew the kids could go to the center and she would make sure they got something to eat.” Simms has given the children clothing. When Elheazy has had to take her mother to the hospital in a medical emergency, Simms has taken care of the kids so she didn’t have to worry.

“She has just always been there for a great support,” Elheazy said. Simms has of course taught the children important educational skills. But Elheazy now sees child care as far more than that. “I don’t think they get the credit that they’re due because they do a lot. They form a family. They form a bond with the children and with the parents,” she said.

Going without the center’s help on Monday while Simms is shut down won’t be easy for Elheazy. She’s had to cancel all of her appointments and do nothing but care for her kids. But she still supports Simms’s decision. “I am all for them closing down for a day to say, ‘Hey, we’re going to close down because this is what we need, we’re not getting what we need. Y’all need to listen to us, y’all need to hear us,’” she said. “If it means them getting their voices heard then I’m all for it, because I can’t imagine one day without the center, let alone weeks or months.” She knows that if the center were to have to shut down for good she would be far worse off. She wouldn’t have a way to give the kids breakfast or even the time to go to the grocery store. She would have to miss her appointments to take care of her shoulder. And, without the time to care for her mother, she thinks she’d have to put her in a nursing facility.

“I don’t know what the world would be like without the center,” she said.

Simms has served many people like Elheazy and her family over the decades. She took over the current location of her business from someone who opened it in 1959. Playtime Nursery School is a “pillar of the community,” she said, “that has educated and brought up so many different varieties of children.” Many of the children she serves are second or third generation, with a grandparent, parent, aunt or uncle who went to the same center when they were kids. Some of her students have gone on to be doctors, others police officers. One mother struggled with her son, who had trouble learning, but Simms told her, “He’s smart, he’s a scientist, he’s going to be an engineer, he’s going to do something.” Lo and behold, today he’s an engineer. “I am able to help many families and many children get their full potential,” Simms said.

But it takes a massive amount of underpaid work. The center serves kids as young as 18 months old to as old as 13 years old. Simms opens her doors at 5:30 to care for children before they go to school, then educates younger kids during the school day, and at the end of the day also has school-aged kids for after school. Without more resources to hire more teachers and staff, Simms takes on multiple roles throughout the day. “I am the administration, I am the school bus driver, I am the preschool lead teacher,” she said. She sometimes arrives at work at 3:30 just to get paperwork done. When she opens her doors she watches the early kids, then after they leave, she oversees the preschool classroom. She then picks kids up from schools at 2:00 and watches them until 5:00. “Sometimes I don’t get home until 10:30 at night because I’m doing administration work,” she said.

“We’re educational programs just like a school district,” Simms said. “Pay us what we’re worth.”

Bryce Covert

Bryce Covert is an independent journalist writing about the economy. She is a contributing op-ed writer at the New York Times and a contributing writer at The Nation. Her writing has appeared in Time Magazine, the Washington Post, New York Magazine, the New Republic, Slate, and others, and she won a 2016 Exceptional Merit in Media Award from the National Women’s Political Caucus. She has appeared on ABC, CBS, MSNBC, NPR, and other outlets. She was previously Economic Editor at ThinkProgress, Editor of the Roosevelt Institute’s Next New Deal blog, and a contributor at Forbes. She also worked as a financial reporter and head of the energy sector at mergermarket, an online newswire that is part of the Financial Times group.