Just as Early Learning Nation showcases the ways families, researchers and grassroots nonprofits and organizations are building an early learning nation—one community at a time—our Community Cultivators series highlights how innovators across all sectors build and sustain global communities from the ground up. We hope the series inspires your own early childhood work.

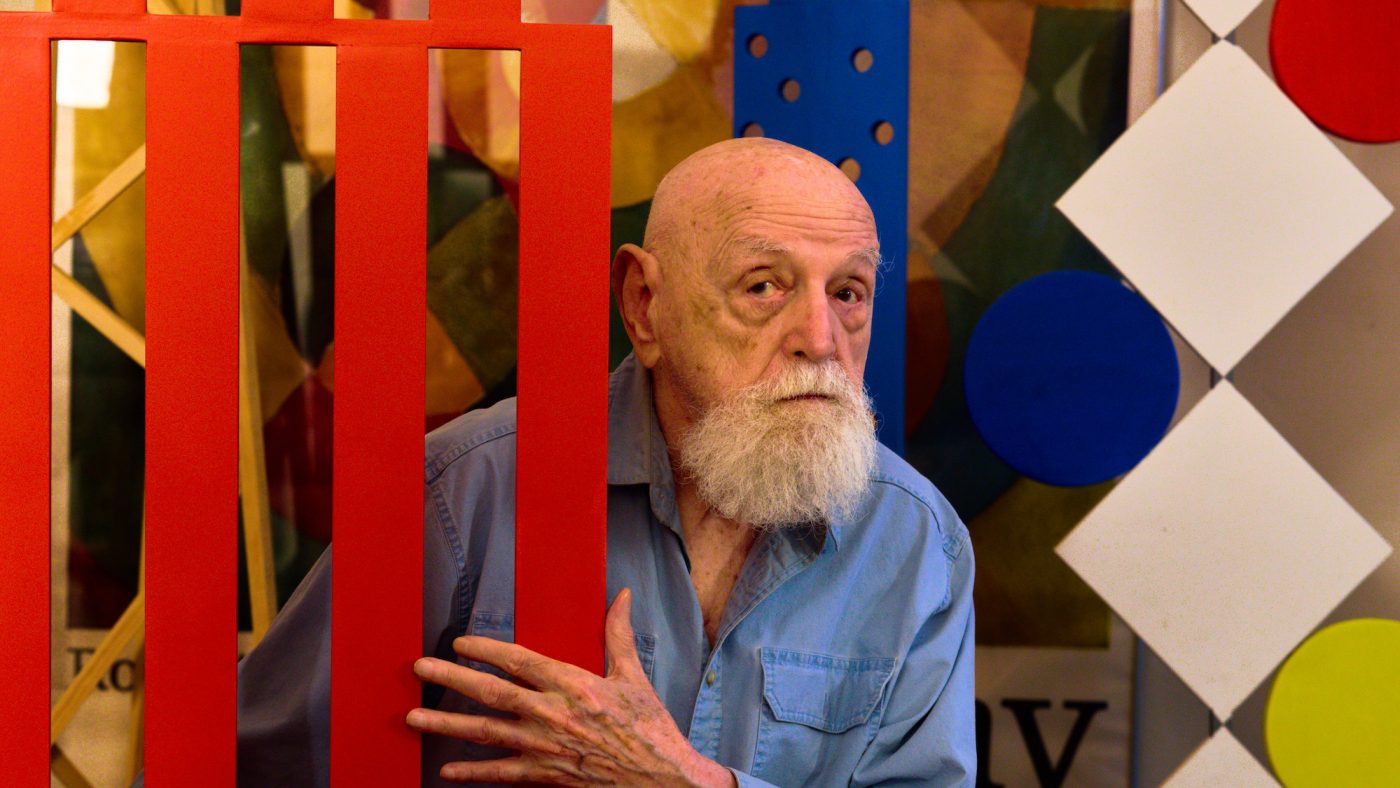

The 92-year-old artist Duane Michals might not seem like an obvious figure to feature in a magazine about early learning. However, his understanding of the world and the many-splendored nature of his work from the past 60 years or more should inspire anyone attempting to see the world through the eyes of a child.

Born in a suburb of Pittsburgh in 1932, Michals is best known for his photographic portraits, but he has worked in a wide variety of media. In each of them he seeks “surprise and contradiction,” following his curiosity and immersing himself in what he calls “the pleasure of chaos.”

In the words of Linda Benedict-Jones, curator of the 2014 exhibition Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh: “Michals often poses big questions that have no easy answers. His images provide a pathway to our own thoughts and fears, our own recollections of growing up, our own dreams and desires, our own concerns about the passage of time and death. He takes us to places we hadn’t planned on visiting; yet when we go there with him, the surroundings are strangely familiar.”

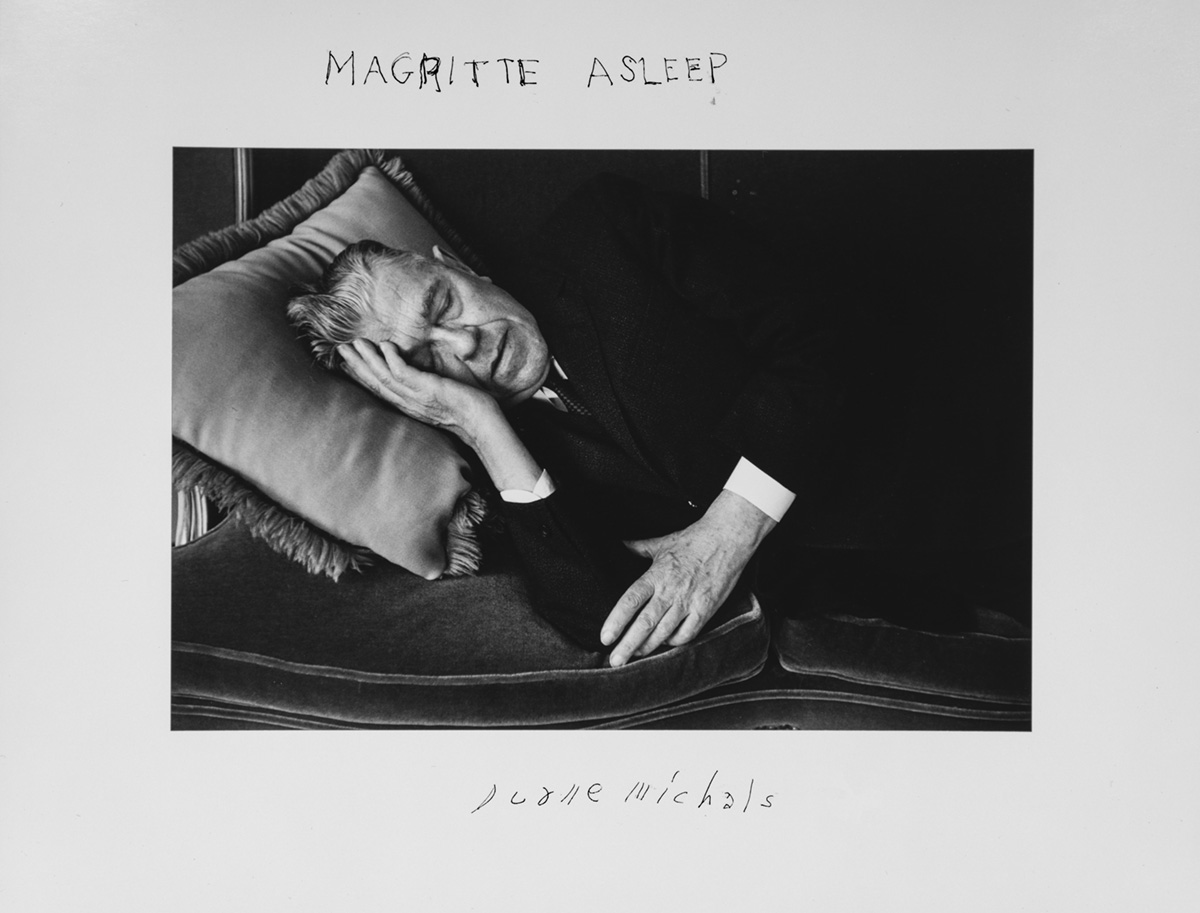

For Michals, art and poetry are “forms of intimacy, the ability to say a secret out loud.” His first artistic heroes were illustrator Rockwell Kent and surrealist painters Giorgio de Chirico and René Magritte, all of whom he met and photographed.

“Art cannot simply be show-off expensive paintings in Park Avenue apartments,” he argues. “It has to be for people. It must get down to the neighborhood.” (Speaking of neighborhoods, as in “It’s a beautiful day in the…,” Michals is a great admirer of another Pittsburgh figure from his generation, Mister Rogers, about whom he says, “Entertainer is the least of his importance. He set a standard of connection between grownups and children.”)

👉 The Last Sentimentalist (The New Yorker)

5 Lessons Early Learning Nation magazine learned from Michals:

1.It all started in Pittsburgh. “I have this very strange passion for Pittsburgh,” he says. “I don’t know why, but it’s one of the most beautiful cities in the country. Most people who become successful in New York don’t remember where they’re from.” (Here he might be referring to Andy Warhol, whom he photographed with Warhol’s mother.)

Michals remembers German rye bread wrapped in white paper, which his grandmother—who raised him until he was five or six—would save so he could draw on it. His father was a steel worker in Duquesne; his mother worked at Kaufmann’s department store; and one uncle drove the number 6 trolley (another echo of Mister Rogers).

“We had no credentials of any value,” Michals says. “We never belonged to the country club. I grew up on the only dirt street in McKeesport. Believe me, we were poor. And I loved it.”

2.Fairy tales reach children’s hearts. Mysterious, frightening and sometimes a bit violent, this form of children’s literature has a much longer history and goes far deeper than Dr. Seuss. As the child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim wrote in “The Uses of Enchantment” (1976): “The fairy tale proceeds in a manner which conforms to the way a child thinks and experiences the world; this is why the fairy tale is so convincing to him. He can gain much better solace from a fairy tale than he can from an effort to comfort him based on adult reasoning and viewpoints.”

One of Michals’s current projects, The McKeesport Pipe Palace Folly, proposes evoking fairy tales through series of structures spread around his hometown. He conjures the scene: “Imagine going to grandmother’s house. Along the way, you encounter this little miniature house with the name of somebody who once lived there. And then you go further. There’s a big one, it’s five feet tall, and there’s a frame of a house with another name. And then there’s another one, which is even bigger.”

👉 Duane Michals Searches the Morgan [Library] and Finds Himself (The New York Times)

3.Leave room for silliness. Nonsense, as practiced by the 17th-century French playwright Molière and Edward Lear (1812-88), among others, animates Michals’ work and his conversation. “I can’t stand common sense,” he contends. “The best defense against common sense is nonsense.”

Science has its place and time, but the artist prefers sticking with his own illogical explanations for how the world works. “If you’re very serious,” he says, “You have to be very foolish to the same degree.”

Perhaps, specialists in early learning underestimate the value of silliness, but as Marilee Hartling of Early Childhood Development Associates has written, “Kids learn most effectively when things are joyful. Engaging in silly play with your children to ‘lighten things up’ is a great way to facilitate learning and help your child’s future success, no matter how you define it.

4.Mistakes make us human. Michals would rather giggle at his own mistakes than analyze one his artworks. “If you already know what you’re going to do, then you’re not being creative, you’re just regurgitating,” he says. “You should never do the same thing twice, and you should never take the same photograph twice.

If you know what you’re doing, then where’s the discovery? Where’s the mistake? Mistakes are very important.” Unintentionally, the artist is echoing Jessica Lahey’s The Gift of Failure, which argues, “The setbacks, mistakes, miscalculations and failures we have shoved out of our children’s way are the very experiences that teach them how to be resourceful, persistent, innovative and resilient citizens of this world.”

5.Astonished people astonish people. Michals tells this story about the French artist and stage designer Jean Cocteau: “As a young man, Cocteau was like the Andy Warhol of his time. Summoned by the Russian ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev, he asked, ‘What do you expect from me? What do you want?’ And Diaghilev said, ‘Astound me.’”

Whether you’re an artist, a teacher or a parent, Michals encourages you to “free yourself to go where you’ve not gone before.” Your sense of astonishment will carry over to the children and other living things around you. “It’s the opposite of being cool or bored and asking how much things sell for,” Michals says. “It has nothing to do with money.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.