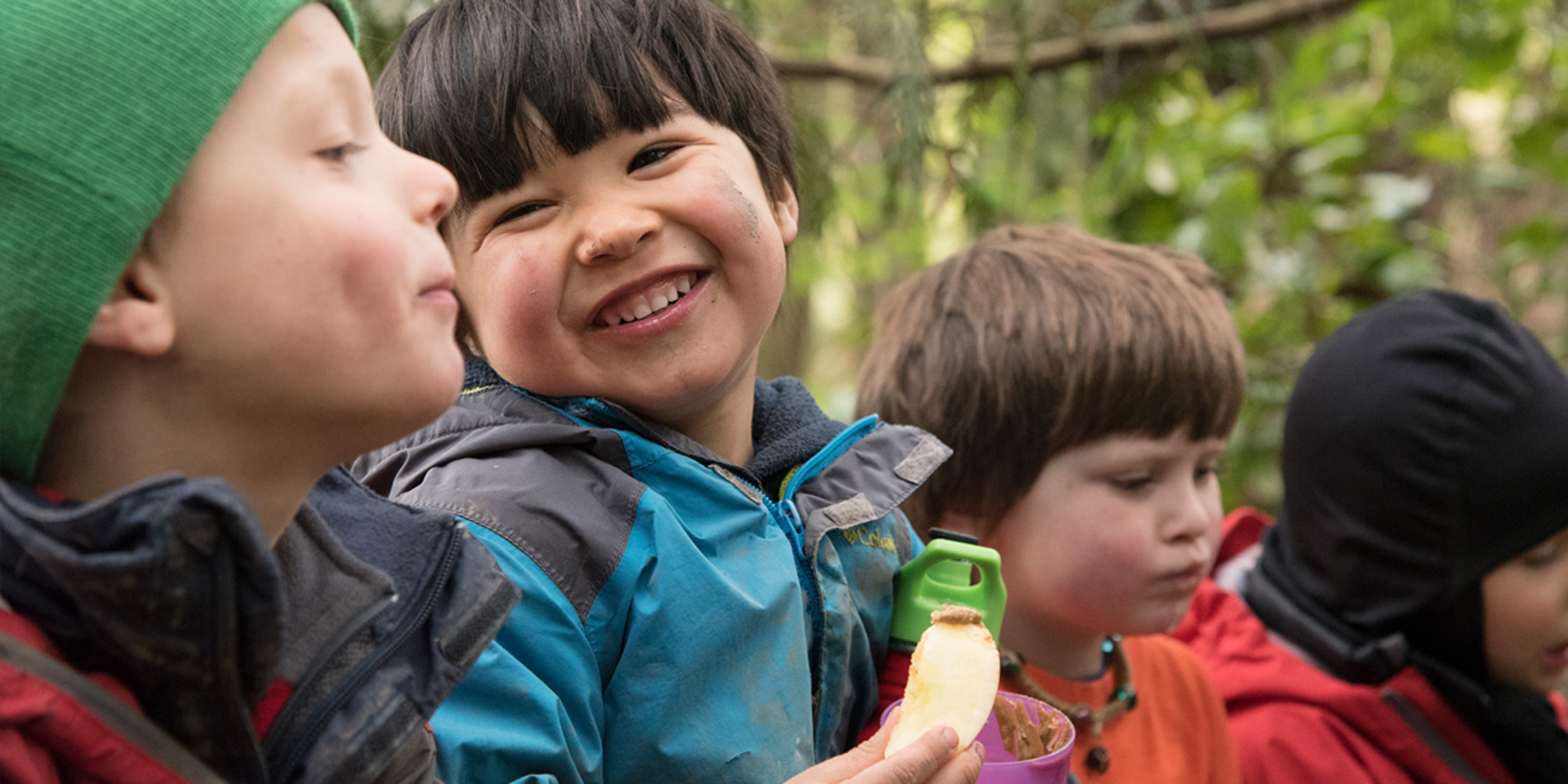

Tiny Trees Preschoolers Get to Know Their World, Rain or Shine

Exciting research in artificial intelligence (AI) has found that computers programmed to “think” and then allowed to engage in unsupervised learning develop the capacity to teach themselves to do a variety of different tasks rather than sticking to the functions set up by their human programmers. The computers’ strength lies in their ability to make mistakes, then learn from them to make better-educated choices in the future.

Even for computers, says Dr. Alison Gopnik, author and internationally recognized leader in the study of children’s learning, unstructured play that gives curiosity free rein creates a stronger, more resilient mechanism for thinking about the world in a creative, generalized way. For children, the ability to go where curiosity leads them creates the capacity to be self-driven, self-motivated learners.

Developing those skills, Gopnik says, is much harder if a child spends all day inside a school room.

“The idea of a childhood that’s mostly spent inside with adults determining what you do is actually very strange from a historical, evolutionary perspective,” Gopnik says. “It’s something of an aberration that we now have the childhoods we do (in the U.S.).

“If you look anthropologically at kids in other cultures, most of the time from when they are very little, children are interacting with animals and exploring — importantly, going out and exploring on their own. Exploring the forest or the natural world around them, sometimes with groups of other children, without a lot of adult hovering and supervision.”

If we were a forager culture, or even a society in which outdoor life were integrated into adult experience, such knowledge and natural connection would happen as a matter of course. That is not the case in the world most of us inhabit.

“We have to have public support for programs like this if that kind of learning is going to happen,” Gopnik says. “We can’t just rely on the fact that this natural infrastructure is available anymore. We need institutions that can come in and help.”

Washington State Makes A Commitment to Get Kids Outside – Serves as Model for Others

The Washington State Legislature has embraced that mission. Inspired in part by journalist Richard Louv’s 2005 book, Last Child in the Woods, Washington’s legislature created the No Child Left Inside grant program to provide the state’s young people quality opportunities to be outside in the natural world. Focusing on under-served populations, the program is designed to empower local communities to create outdoor programming. The Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission has now received funding to the tune of $1.5 million every biennium for the program.

“The ‘nature deficit disorder’ described in Last Child in the Woods underscored this fear that we are losing a generation to online activities instead of experience in the outdoors,” says Jon Snyder, senior policy advisor on Outdoor Recreation and Economic Development for Washington Governor Jay Inslee.

“Two things are putting roadblocks in front of kids these days. One is the all-encompassing online environment that is so powerful and alluring—and even vital in some ways—that it’s incredibly engaging and enveloping for children. On top of that, we’re paving over impervious surfaces and developing our natural places at a pretty fast clip, so a lot of folks felt that access and the ability of kids to have these experiences was in jeopardy.”

Because affluent Washingtonians generally have access to the outdoors and the leisure and equipment to enjoy their experience, the Washington State program is particularly focused on “under-served” populations. This includes low-income communities and urban communities of color, but also very rural communities with immigrant populations, such as programs serving the families of farm workers in the agricultural Yakima area. Grants cover programs for preschoolers, such as the Tiny Trees outdoor preschool (see companion article), to high schoolers such as the North Cascades Institute’s youth leadership program.

Washington wants its children outdoors: The program has proven so successful that the last funding round saw five times as many applications for the program as could be funded, according to Kyle Guzlas, grant services section manager for the Recreation and Conservation Office, which administers the grant program on behalf of the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission.

“This year was the most competitive grant round we’ve seen, with applications from all over the state,” Guzlas says. “We had 173 applications and were only able to provide funding for 30 projects. It’s pretty clear from how competitive it is that there are a lot of great projects not getting funded because we just need more money for the program. So, a coalition of nonprofits and citizens are working toward encouraging the Legislature and the governor’s office to allocate more in the future.”

“We know from existing data that there are benefits to academic performance, and benefits to the kids’ health and self-esteem. With these experiences in the outdoors, children begin to understand who they are and develop a sense of personal responsibility and an understanding of how they relate socially and within their communities.

“Equally important is that they start to understand about natural resources and concepts of conservation,” he says. Some of the programs are designed to provide pathways that take children from an outdoor preschool environment to outdoor leadership experiences in middle school. By the time they are in high school, some of these young people will be peers who are counseling and mentoring the next generation of kids coming through.

“If they go to college, maybe some will want to study biology or wildlife sciences,” Guzlas says. “The pathway approach is creating the ethics of natural resource conservation throughout the whole structure in terms of understanding nature. You create a comfort level at a very early age that becomes ingrained.”

Most of the organizations that receive funding are collecting data and doing their own analyses of results, which then become part of the feedback loop for the governor’s office and Legislature in looking at future funding.

- More insight from Alison Gopnik as well as links to her books can be found on her website.

- The Children and Nature Network is leading a movement to connect children with nature.

- The Child Mind Institute has a deep database of research and resources on strengthening children’s’ lives.

- Here’s a good explainer on the distinctions in learning approaches for AI: Supervised vs. Unsupervised Machine Learning: What’s the Difference?

- Act Naturally: The Benefits of Wet Hands and Muddy Feet; An Interview with Richard Louv

According to Snyder, Washington state’s program is being used as a model across the country, with states including Minnesota and New Mexico creating similar programs. In Oregon, voters passed the Outdoor School Education Fund mandating an outdoor school program that gives all of the state’s fifth and sixth graders a week-long outdoor education experience and approved $24 million for the program’s first two years. More than 30,000 children attended in the program’s first year.

“The next frontier for this [type of programming],” Snyder says, “is understanding outdoor recreation as a health and mental health intervention. The University of Washington and Earth Lab are leading the way in working on exploring the relationship between nature and human health.”

Its role as a mental-health intervention may be one of the most valuable benefits to spending time in nature. From the calming effects of Japanese “forest bathing” to the confidence-building experience of learning to successfully react to unpredictable events, being in nature helps strengthen the human emotional scaffolding. Yet, according to the Child Mind Institute, despite evidence to the contrary, increasing parental fears about diseases and dangers of playing outside are a big factor in keeping children cooped up.

“I find this baffling and mysterious,” Gopnik says. “There is so much less danger these days and yet people are so frightened and protective of their children. The crime rate and even the accident rate have gone down and by any standards, children are much safer than they have been in the past.

Terror and fear become a reinforcing process she says. “When you’re terrified, that just makes you more terrified. Telling children everything around them is scary is a good way of making them scared. There’s something of an analogy to the rise in allergies, where if the system doesn’t have a chance to face risks it can deal with itself, then it starts going off even when there’s actually nothing to react to.

“One of the things we know about anxiety is that not being exposed to risk makes you more anxious. The way to cure anxiety is to expose people to the thing they’re frightened of, so if throughout your whole childhood, which is when you should be starting to deal with risk, you never get a chance to effectively deal with it, that seems like a pretty good recipe for anxiety as an adult.”

The antidote can be as simple as a trip to the beach or a park or the forest. The harder part for some of us is to let the children play while we master the fine art of minimal intervention.

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.