This is why we can’t have nice things. Finally, at long last, bipartisan momentum is building towards an affordable, accessible, universal child care system in the United States. Almost like clockwork, a clutch of conservatives are pushing back. The latest swipe comes in the form of an essay published by the American Enterprise Institute’s Katharine B. Stevens and The Wheatley Institution’s Jenet Erickson: “Universal Child Care: A Bad Deal For Kids?” The arguments Stevens and Erickson advance are so out of touch with the research consensus as to be almost a caricature. As Ellen Galinsky, Chief Science Officer at the Bezos Family Foundation, put it in an email: “The real problem is that this blog tries to take us back to an either/or stance, something that most people who study children’s development and work and family thought we had moved beyond long, long ago.”

Nonetheless, it is important to rebut these claims. Much like climate science, all that opponents of seriously addressing child care need are a few scholarly names on which to rest their denial of reality, regardless of the authors’ intentions. For once and for all, it’s time to put the ideas that child care harms children, or that parents don’t want or need external care, into their overdue grave.

The (Non-Cherry Picked) Evidence on the Impact of Child Care on Child Development

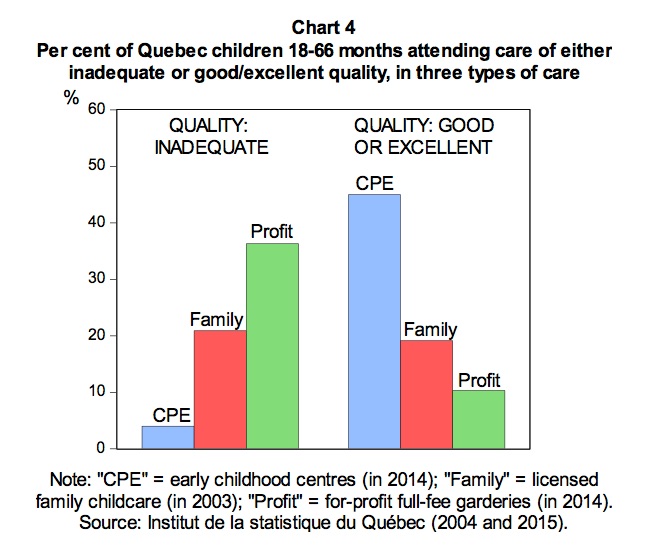

Stevens and Erickson use two pieces of evidence to try to paint the picture that lots of time in external child care is bad for kids: Quebec’s experience, and a 2003 report from a cohort of U.S. children followed over many years. The problem is, this evidence doesn’t show what they want to bend it to show. The actual conclusion is, as any child care advocate or researcher worth their salt will tell you, low-quality child care can hurt child development, while high-quality child care can help. Indeed, their assertions are almost predicated on a hope no one takes the time to go back to the source material. As Steven Barnett, co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research, wrote in an email: “Yes, children are harmed by disorganized, stressful environments — which is why we must ensure child care is high quality. Other studies find positive impacts of higher quality programs and also that maternal employment is not a negative.”

“Notably, based on the Quebec Longitudinal Survey of Child Development, 12-year-olds (grade 6) from low socioeconomic status families who had been in centre-based care (mostly CPEs in the sample) had cognitive outcomes that were (1) significantly better than if they had not attended CPEs, (2) even better if attendance had been intensive (around 40 hours/week), and (3) similar to those from adequate socioeconomic status families if the CPEs had been attended early (from 18 months old). Further analysis suggested that early participation in centre-based childcare can eliminate the social inequalities in academic performance at least up to early adolescence.”

(Oh, and the flashy “more child care leads to more crime!” study, it will probably not shock you to learn, has been deeply criticized as flawed by other researchers.)

As you can see below, Quebec certainly has quality issues and their experience speaks to the need to scale up carefully and with enough public money to ensure quality across the board. The cautionary tale, then, is not about a child care boogeyman — it’s about the impossibility of building a high-quality system in the U.S. without tremendous new investments, because wages are so pathetic that between one-third and one-half of the workforce turns over every year.

Turning to the 2003 report, here Stevens and Erickson are basically pointing to a molehill and calling it a mountain. The study authors themselves note that “The magnitude of quantity of care effects were modest and smaller than those of maternal sensitivity and indicators of family socioeconomic status.” The very same edition of the journal had two commentaries arguing that those modest findings reveal not an inherent flaw in external care, but the need to improve different elements of care (features like how groups are structured, and how peer interactions are managed). As Barnett puts it, “This is a very complex story.”

Turning to the 2003 report, here Stevens and Erickson are basically pointing to a molehill and calling it a mountain. The study authors themselves note that “The magnitude of quantity of care effects were modest and smaller than those of maternal sensitivity and indicators of family socioeconomic status.” The very same edition of the journal had two commentaries arguing that those modest findings reveal not an inherent flaw in external care, but the need to improve different elements of care (features like how groups are structured, and how peer interactions are managed). As Barnett puts it, “This is a very complex story.”

Indeed, in the intervening two decades since research like this came out, the child care field has broadly adopted more evidence-aligned practices. Galinsky added that, “Since [these] studies were conducted, the science has advanced, becoming even more explicit about how we can ensure that children thrive at home and in child care.”

While we’re talking about evidence from around the turn of the Millennium, it’s curious that Stevens and Erickson fail to mention From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development, a monumental 600-page interdisciplinary research report produced in 2000 by the National Research Council. If they had, they would have had to include the researchers’ conclusion that “the positive relation between child care quality and virtually every facet of children’s development that has been studied is one of the most consistent findings in developmental science.”

Stevens and Erickson go on to express concern that more child care will lead to “less parenting,” and therefore harm children, but they actually give child care too much credit. The power and influence of children’s attachment to primary parental caregivers is rock-solid. Neurons to Neighborhoods, again:

“In sum, despite persistent concern about the effects of child care on the mother-infant relationship, the weight of the evidence is reassuring, with the possible exception of emerging findings regarding very early, extensive exposure to care of dubious quality … If anything, the child care research of the past decade has enhanced appreciation of the potent influence of parents on early development. When child care effects are examined net of parental effects on child outcomes, parent’s behaviors and beliefs show substantially larger associations with their children’s development than do any features of the child care arrangement.”

So, in the end, the research base is actually an argument for more investments in external child care to ensure its quality and for big child allowances to help stabilize families, particularly lower-income ones. To Galinsky’s point, an either/or formulation here is as wrongheaded as it is antiquated. Basically, if you want children to thrive, focus on family stability and on having enough money in the system to pay child care teachers well.

The (Non-Cherry Picked) Evidence on What Parents Want and What Kids Need

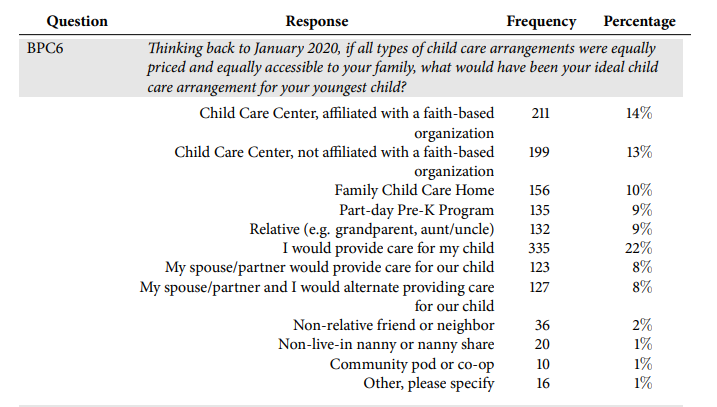

Here again, Stevens and Erickson go back 20 years(!) for a report called Necessary Compromises to claim parents don’t actually want formal child care. They are certainly correct that parents have wildly different preferences when it comes to how much they work — but they wildly overreach in their conclusions. Once again, we can actually look at current data: the Bipartisan Policy Center recently released poll results that asked parents, if affordability and access weren’t factors, what their ideal child care setup would be. The responses make it clear that many parents value external child care, just as many value parental and relative care.

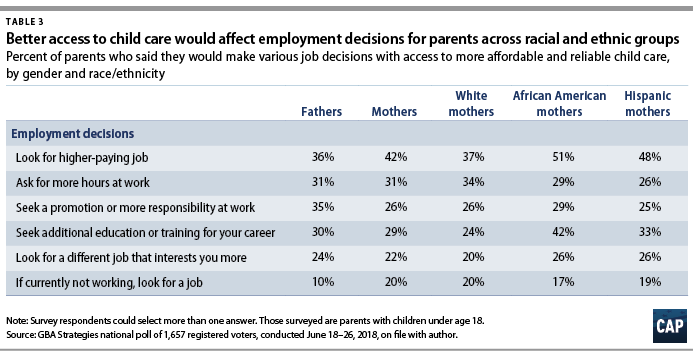

Stevens and Erickson do correctly note that universal or near-universal child care programs tend to lead to almost immediate increases in maternal employment. Bizarrely, though, that’s a point in favor of the need for better child care services: it shows many women would like to increase their labor force participation but can’t due to child care problems. We also have modern data on this: the Center for American Progress analyzed a 2018 survey and found the following — as you can see below, one in five mothers not currently working due to care challenges would like to look for a job. Contrastingly, surveys show about one in ten women currently working would prefer to not work at all.

Moreover, having a parent at home is not “generally best for children,” as the pair assert. What is generally best for children is having stable and overall happy families, as well as ecosystems of positive relationships. As Galinsky put it, “Yes, children do need ongoing, nurturing interactions with their parents. What’s missing here is the assumptions that parents should raise their children alone and that isn’t correct. All of us, employed or not, need support in raising our children. And children, whether their parents are employed or not, need relationships with caring others.”

Moreover, having a parent at home is not “generally best for children,” as the pair assert. What is generally best for children is having stable and overall happy families, as well as ecosystems of positive relationships. As Galinsky put it, “Yes, children do need ongoing, nurturing interactions with their parents. What’s missing here is the assumptions that parents should raise their children alone and that isn’t correct. All of us, employed or not, need support in raising our children. And children, whether their parents are employed or not, need relationships with caring others.”

Consigning one parent (guess which one!), against their will, to be a stay-at-home parent — and the financial consequences that go along with that — is an ugly and scientifically unsupported perspective. It’s easy to imagine a similar argument being made in fighting against previous child care bills: it’s easy because, in fact, ‘best for mother, best for child’ has been the rock thrown against public child care for over a century. We now know better. In fact, new evidence suggests that reducing the number of hours a mother is providing care may increase the quality of maternal care overall, because it reduces the exhaustion any parents knows comes along with the caregiving territory.

A very complex story, indeed.

The (Just Plain Odd) Proposal

It’s barely worth going into the authors’ proposed ‘solution’ because it arguably doesn’t even qualify as one. The first thing you should know is that they don’t think poor families need any new help nor do they propose to give them any. Rather, through some magical thinking, “significant untapped opportunities” in existing Medicaid, WIC and SNAP programs are going to do the trick (notably, these opportunities go unnamed). By their own admission, their proposal would “offer limited assistance to families with no work income.” The maximum benefits to a family of four would only be available to those making $36,000 a year or more. Given the deep literature about the negative effects of poverty on child and family development, this hand-waving away of the millions of families with children living under the poverty line falls somewhere between thoughtless and callous.

For everyone else, Stevens (who co-authored a paper on the idea with Matt Weidinger) wants to provide a “flexible child tax credit,” which involves “giving parents the option to pull up to $30,000 of already-promised future CTC payments into any or all of the first five years of the child’s life, up to a maximum of $15,000 per year.”

This, of course, both fails to generate high-quality child care choices and manages to be an almost unimaginably worse method of family support than proposals on the table to convert the CTC into a de facto child allowance. These proposals would provide thousands of dollars per child to all low- and middle-income Americans, year after year, halving child poverty rates among other boons — and it’s an idea that has strong conservative support from other quarters. (Even the good CTC proposals, it should be noted, are complements and not replacements for publicly-supported child care).

The selling point to this “flexible CTC,” one supposes, is that it doesn’t require the government to spend any more money. Truly, the idea that we can help America’s struggling children and families without spending a penny more is as bold as any universal child care plan.

Conclusion

In the end, we — as always — need to do more than one thing at once to safeguard America’s families: robustly-funded, high-quality universal child care plus a big child allowance plus stipends for stay-at-home parents (plus paid family leave, plus support for elder care and long-term medical care…). All forms of care and caregiving, and all parental preferences, can and should be honored. What we don’t need are retread arguments that allow opponents to dress up, in the veneer of research, a reflexive and bygone opposition to children being cared for by someone who isn’t their mother.

Universal child care is coming. So is a child allowance. These policies will help everyone, and will support true choice in care, a purported goal of the Right. It’s time to set aside the bad-faith arguments, and get on board — or get out of the way.