Author’s Note: This moment, when the world has stopped spinning on its axis, presents an important opportunity to re-examine our society’s early childhood axioms. In this essay series I will examine four key early learning topics and the extent to which our current policies do or do not line up with the research base.

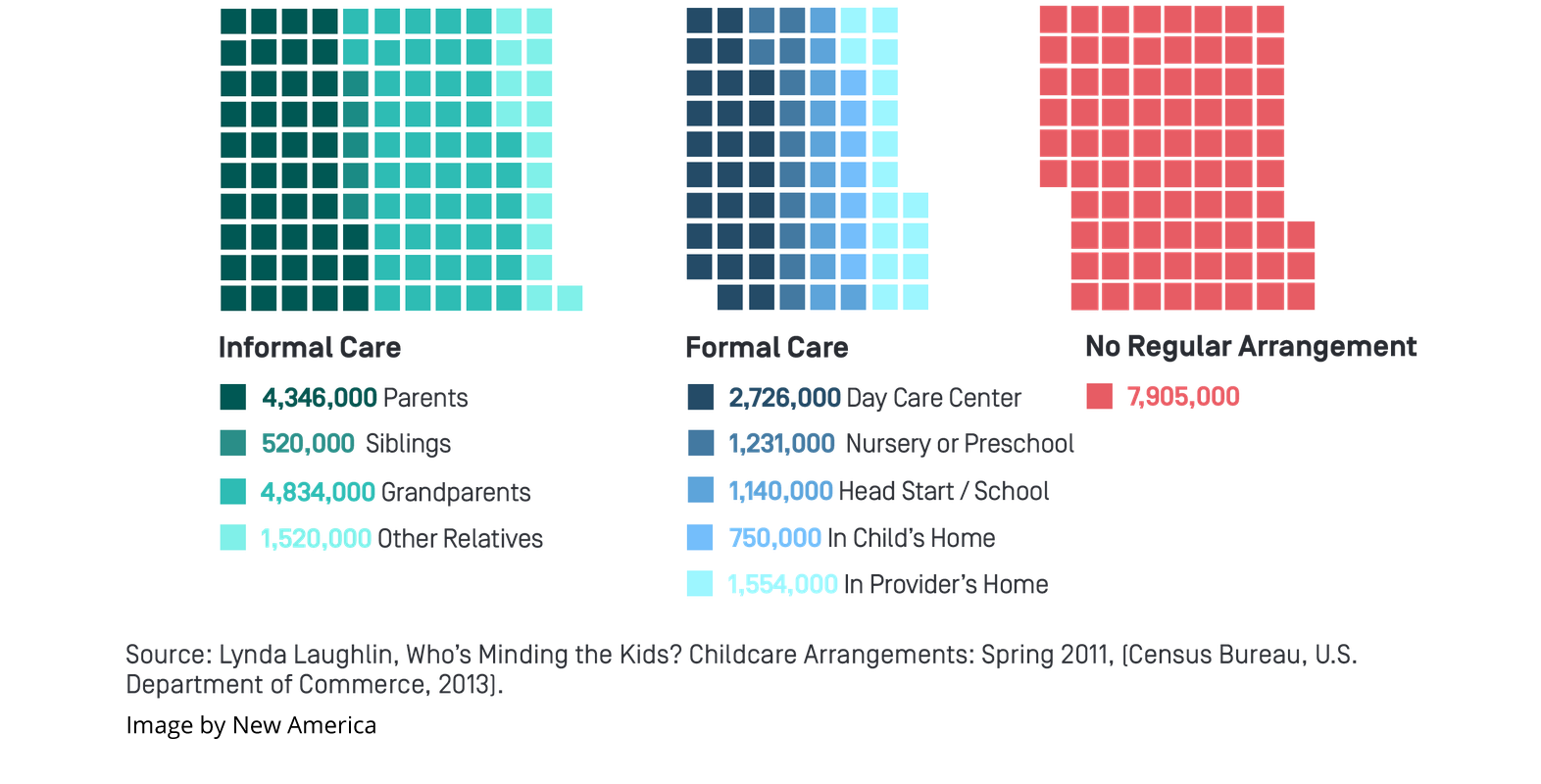

On a normal Monday morning in non-pandemic times, where are most young children being cared for? Based on the amount of attention that child care centers and state-run pre-K programs get, you’d be forgiven for thinking the majority of youngsters attend these types of formal programs.

The truth is that the vast majority are cared for in informal settings, ranging from parental care to relatives to small home-based family child cares. Given this tremendous diversity of early learning settings, it’s important to ask when designing a system: is one setting better than another? The short answer, research tells us, is no. Quality can exist in any setting, and indeed quality matters far more than setting — but that’s not how our early learning policies treat things.

Young Children’s Care Arrangements, Per New America’s Care Index*

Quality in early learning is driven primarily by the warmth and intentionality of interactions between caregiver and child. These interactions are setting agnostic; a child’s brain does not know the difference. The authors of the National Research Council’s blue-ribbon report, “Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation,” put it this way: “All [informal and formal] settings and interactions offer the potential to support healthy development and early learning, and children can meet developmentally informed expectations for early learning when they are immersed in high-quality environments with professionals who are promoting their progress and working in positive ways with their families.”

That said, there is little question that policymakers—and many advocates—prefer formal settings. The push for universal pre-Kindergarten implies that all four-year-olds should be in some type of formal early learning setting. The desire for early childhood educators to hold a bachelor’s degree is similarly preferential to formal programs.

Consequences from these leanings already exist: for instance, as the nation has lost nearly half of its family child care supply over the past 15 years, policymakers have done essentially nothing, instead pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into Preschool Development Grant programs. Parental care, grandparent care, neighbor care — these settings are barely a blip on policymakers’ radar.

There is some logic behind this. Formal settings are easier to regulate and monitor, whereas it can be difficult to even identify who is providing informal care. Moreover, although all settings offer the opportunity for quality, research has revealed that informal settings are not identical to formal ones. Stanford University education professor Susanna Loeb has written of a study she co-authored:

“Television watching is perhaps the most vivid contrast. Four-year-olds in home-based, informal care watch an average of almost two hours of television per day, compared with fewer than 7 minutes in formal care. Similarly, in formal arrangements for four-year-olds, 93 percent of caregivers reported doing both reading and math activities on a daily basis. By contrast, 68 percent of informal sector caregivers reported daily reading, and 60 percent reported daily math.”

Yet these items are proxies for quality, not quality themselves. As early childhood expert Erika Chistakis wrote in her book The Importance of Being Little: What Young Children Really Need from Grownups:

“Do preschoolers need all the trappings of elementary school…? The faux academic overstimulation? The enforced choices? The cult-like obsession with readiness? I would say, mostly, they do not. And I think some of these trappings, such as the notorious print-rich environments we encountered with their busy totems to industriousness, can actually interfere with the task of becoming a good communicator and a literate person. We spend a lot of energy on creating print-rich environments but that’s not at all the same thing as creating a language-rich environment.”

These are vital efforts that should be looked to as national examples. More public funding would also allow family child cares to hire additional staff support. As many as 80 percent of family child care providers in some states have a single owner-operator-educator. It becomes much easier to conduct literacy and math activities with another set of hands around to handle a tantrum or bathroom need.

Friend, family and neighbor (FFN) caregivers are perhaps even more isolated — alone in a boat circling the island, to stretch the analogy. There are vanishingly few structured supports for these caregivers, even though they are by far the leading sources of care for infants and toddlers in particular. This is, in a sense, the shadow side to well-intentioned efforts to professionalize the early learning field. After all, if an educator requires training and/or a degree to be deemed effective, what ultimately does that suggest for parents or grandparents who are ‘untrained’? It’s a deeply uncomfortable tension that is rarely mentioned, but one that must be reckoned with.

Promising supports for FFNs do exist, most often methods of providing organic learning opportunities for child and caregiver alike. For instance, a Charlottesville (VA) nonprofit, ReadyKids, offers free weekly early learning playgroups where caregivers can observe best practice modeling and also create social connections among one another. Hawai’i has a similar program, Tutu and Me, specifically focused on grandparents. In New Orleans, a group called TrainingGrounds operates a drop-in early learning center which offers workshops and seminars for caregivers. These initiatives are deserving of public funding. Another form of potential support, which exists in many Northern European nations but has only been floated in the U.S., is a ‘caregiver stipend’ payment for stay-at-home parents, enabling them to better access early learning resources.

Any way you cut it, America’s current early care and education policies have a distinct bias towards formal settings. It’s important to note that formal and informal settings are not opposite sides of a see-saw; there’s no reason to deemphasize formal care. Research clearly points, however, toward taking a more comprehensive and differentiated approach to supporting quality care across the board. The entire early learning sector, to say nothing of parents and children, will be better off for it.