One of the less-remarked-upon consequences of the COVID-19 epidemic is the discontinuation of prison visits. Suddenly, Flikshop Angels, a program made for the 2.7 million children (1 in 28) in the U.S. who currently have a parent behind bars, has become even more necessary. With the Flikshop app, families can send a picture postcard using just a smartphone.

“There is no internet in prison,” says Marcus Bullock, founder of Flikshop. “No texting or Facebook. These postcards are their lifeline, their reminder that the outside world is waiting.”

👉 Read more: These valentines headed to prisons and detention centers across the country are heartbreaking and revealing (Washington Post, February 2020)

“Being an entrepreneur is part of my DNA,” Bullock says. He recalls selling Blow Pops, Now and Laters and Nerds as a child in the D.C. area, and how it felt to break sales records he set for himself. He recognized then that his customers—his classmates—would pay more on the school bus than out on the street when they had access to other sources. This lesson in supply and demand has always stayed with him.

When Bullock went to federal prison at age fifteen, he discovered another example of spiking demand. While the young men incarcerated with him were starved for contact with the outside world, the 4:00 p.m. mail call always brought him letters from his mother. “Every envelope stuffed with photographs,” he recalls, “would fuel hours of conversation in the dayroom. Guys who never knew my family became engrossed in every detail of my home life.”

This connection sustained Bullock and propelled him toward a career and life goals when he was released eight years later, first as owner of a house painting business that employed returning citizens, and now as CEO of what has become known as the Instagram of Incarceration.

On the Flikshop app, relatives—or even strangers who want to connect with someone behind bars—can upload a photo and a note that gets converted into a print postcard and sent via the United States Postal Service. One study notes how Flikshop’s business model “empowers the offender.” To date, more than 500,000 Flikshop messages have gone to more than 80,000 incarcerated people.

Connected by our mutual friend, the artist and poet Halim Flowers, Bullock and I met (just before the COVID pandemic hit with its full force) in Washington D.C’s Halcyon Incubator, where he and Flikshop’s COO Camille Clark are currently fellows, developing growth strategies with the help of leading entrepreneurs.

“This is a game-changing platform,” says Halcyon’s Mike Malloy. “I’m grateful for Flikshop giving me the ability to send love, pictures and messages of holiday cheer to one of my former colleagues in a California correctional facility.”

Malloy, an entrepreneur himself who previously ran Waveborn Sunglasses, adds, “Marcus and Camille are two sensationally smart, hard-working and driven entrepreneurs. Their collaborative personalities, coachable spirits and eagerness to grow and scale Flikshop makes them a dynamic duo who continue to attract customers, advisors and investors to support Flikshop’s long-term vision.”

Bullock plans to branch out into nursing homes and other settings beset by social isolation. In the seven years since setting up the app, he’s launched two spinoff operations: Flikshop Angels and the Flikshop School of Business, which helps inmates to envision and build startups of their own.

In all of his ventures, Bullock promotes three rules that he says apply to virtually any important goal.

- Stay connected to friends and family

- Have mentors who show what can be done

- Be surrounded by people to push you to be great

“Of course,” he adds, “You have to be willing to work hard, too.”

The evidence bears out Bullock’s recollection that his mother’s letters galvanized his post-release success. Urban Institute analysis has found “remarkably consistent association… between family contact during incarceration and lower recidivism rates.” That is, people who stay in touch with their families during their sentences are less likely to resume criminal behavior when they get out and less likely to go back to prison. “It can be something as simple as a picture of your puppy,” Bullock says. “If the person in prison sees your puppy, he’s going to want to meet him when she’s a full-grown dog.”

President George W. Bush highlighted the recidivism problem in his 2004 State of the Union address: “This year,” he said, “Some 600,000 inmates will be released from prison back into society. We know from long experience that if they can’t find work, or a home, or help, they are much more likely to commit more crimes and return to prison…. America is the land of the second chance, and when the gates of the prison open, the path ahead should lead to a better life.” Today, with the number of returning citizens up to 650,000 a year, the challenge remains daunting, with approximately two-thirds rearrested within three years of release.

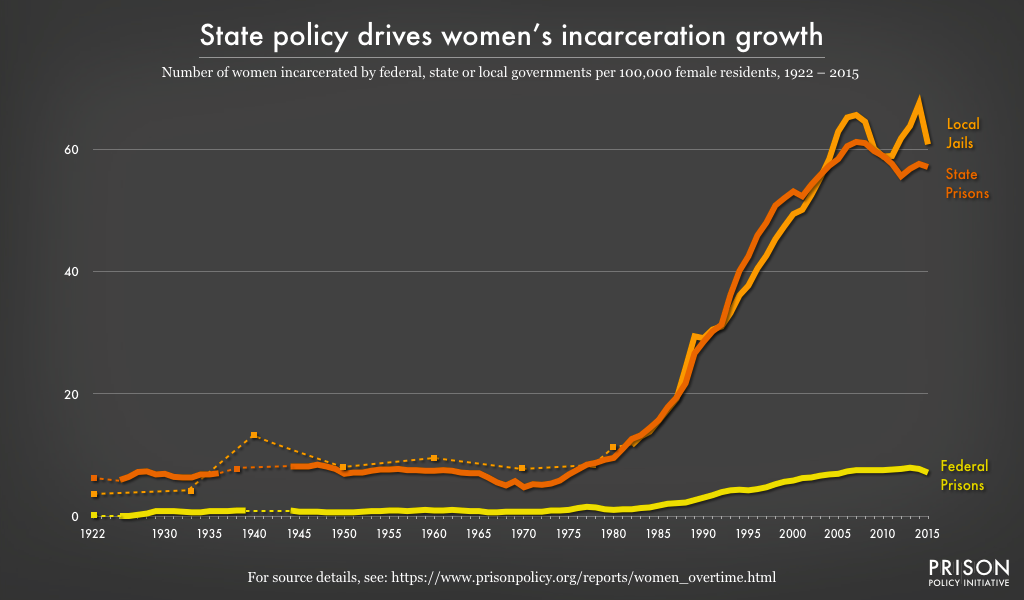

The fastest growing demographic behind bars, Bullock points out, is women. And he doesn’t believe it’s crass or exploitive to regard this statistic as a business opportunity. Women are going to want to see pictures of their loved ones—nearly two-thirds of the women in prison are mothers of young children. While nothing can make up for the loss of in-person contact, a picture and a few words can sustain and even deepen a relationship. Bullock recalls his mother’s correspondence as being more personal and open-hearted than she had ever been before.

The fastest growing demographic behind bars, Bullock points out, is women. And he doesn’t believe it’s crass or exploitive to regard this statistic as a business opportunity. Women are going to want to see pictures of their loved ones—nearly two-thirds of the women in prison are mothers of young children. While nothing can make up for the loss of in-person contact, a picture and a few words can sustain and even deepen a relationship. Bullock recalls his mother’s correspondence as being more personal and open-hearted than she had ever been before.

👉 Read more: Parenting from Prison, Preparing for Coming Home

Asked what he brings to the prison reform movement, Bullock says, “I understand what corporations need to be responsible and to succeed.” As an entrepreneur and devout capitalist, he believes that businesses are more likely than nonprofits to achieve the necessary scale and lasting change. While he appreciates grassroots advocacy (and notes that the ACLU uses Flikshop to contact clients eligible for defense services), he says, “Putting data and analytics in the hands of companies is more likely to change the justice system than what they’re doing.”

Bullock identifies “access to capital” as Flikshop’s number one challenge right now. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, investors were hesitant to get behind an enterprise geared at this market. They say, ‘I don’t want to be the first’,” he says. “Our job is to de-risk the venture and to point out the industries already benefiting from serving the prison population.”

While the predatory prison calling industry and, more egregiously, slave labor, can justly be accused of profiting on the backs of prisoners, Bullock points to the $1 billion commissary business and other enterprises that do better when their customers are happy and satisfied.

In his TED Talk and other appearances, Bullock never fails to credit the woman who sent him letters every day for the final six of the eight years he spent in prison: his mom, Sylvia Bullock—who now works for him as Flikshop’s Head of Partnerships.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.