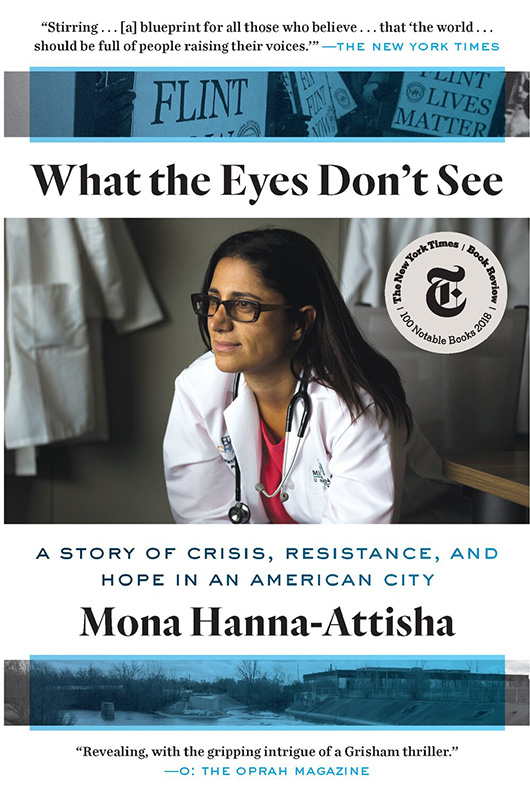

In choosing to quote Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax in the epigraph of her society-shaking book, What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance and Hope in an American City, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha not only sets the tone for the book, she reveals her guiding principles and provides a blueprint for anyone wanting to change the conditions they confront.

Unless someone like you

Cares a whole awful lot

Nothing is going to get better.

It’s not.

Hanna-Attisha’s riveting first-person account of the public health catastrophe that has become known as the Flint water crisis not only lays out the facts of how a government poisoned its own people; it lays open the heart of a doctor who swore an oath to protect the health and lives of the children affected.

The Flint water crisis began in April 2014 when the Michigan city changed its water source from Detroit Water and Sewerage Department—which it had been using for over 50 years—to the Flint River. Elected officials, including Gov. Rick Snyder’s administration, made the switch as part of a budget-slashing, austerity initiative, despite the fact that the Flint River had been an industrial dumping site for decades. The move was made without properly training water-treatment staff or upgrading the plant.

Almost immediately, residents began to raise alarms about foul-smelling, filthy water. As a busy professor and pediatrician at Flint’s Hurley Medical Center as well as a mom of two young daughters, Hanna-Attisha was aware of complaints about the water, but water wasn’t foremost in her mind. She assumed—with the rest of the community—that city and county officials, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) were serious about their job of protecting water quality. She thought they had this.

No, Betanzo said, it’s not. Flint was not using corrosion control, she said, and lead from the city’s old pipes was leaching into the water. Betanzo told her that a research team from Virginia Tech, led by municipal water-quality expert Marc Edwards, had found “really, really high” levels of lead in Flint water. (Edwards’ team ultimately concluded that at least a quarter of Flint households showed lead levels as much as 65 times the federal action level of 15 ppb. Health advocates say that allowable number should be 0 ppb. Some homes Edwards’ team tested showed lead levels of 13,200 ppb.)

Loopholes in the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule allow for utilities to game the regulations and manipulate the data, Batanzo told her. The agencies test for the results they want, not what’s best for the health of the community.

Lead in the water.

Hanna-Attisha’s fate suddenly hit a hairpin turn. All pediatricians know about lead, a powerful neurotoxin that disrupts brain development and is especially harmful for young children, potentially causing life-long, irreversible brain damage, developmental delays, speech problems and an increased risk for behavioral issues and serious chronic conditions. The implications for her Flint kids were horrific.

Even after hearing the facts, she didn’t want to believe them. The MDEQ couldn’t possibly be testing inaccurately or intentionally juking the results of tests that could have such devastating implications for the community? Surely not. But, she writes, her experience as an Iraqi immigrant, knowing that Saddam Hussein had gassed the Kurdish town of Halabja and murdered thousands of his own people, including children, had shown her at an early age what governments could be capable of.

After that conversation, she writes, a “fog of unreality” descended when she realized the enormity of what she—and Flint —were facing. From that point, science and Hanna-Attisha’s self-professed doggedness drove the story.

Balancing her impulse to launch into a full five-alarm Paul Revere moment with the need for a carefully constructed, fact-based scientific report, the devastated doctor began gathering statistics, knowing that every day meant harm to the children. Lead in the water threatened every tomorrow of every one of Flint’s children.

Addressing a public health crisis is like solving a mystery, employing just the right mix of instinct, insight, footwork, solid data, strategy and pure luck, Hanna-Attisha writes. When officialdom or fondly held beliefs get in the way, it’s time to speak science to power. And she did.

She soon found that just six months after the switch, General Motors had stopped using Flint water at its plant because it was so corrosive it was destroying metal engine parts. Despite that, no alarm bells had sounded about what such corrosive water could be doing to the city’s old lead water pipes.

Though her conclusions were soon confirmed in professional journals and published in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, when Hanna-Attisha initially revealed her findings, she did so at great professional risk. Her research had not been peer-reviewed—the gold standard for scientific research—and if she got it wrong, her reputation and that of her hospital would have suffered significant damage. With the lives of children at stake, every day mattered. So, she broke the news, urged residents to stop drinking the water and set in motion the wheels that eventually led to a $641 million settlement for Flint families and indictments against nine public officials, including now-former Gov. Snyder, on 41 individual counts.

The brilliance of Hanna-Attisha’s book isn’t simply a description of events that led up to one of the nation’s most dramatic whistleblower events. What the eyes don’t see, she writes, is not just lead in the water, but the racism, inequity, heartless austerity policies and bureaucratic indifference that led to the crisis in the first place. The book’s title and central metaphor are taken from a D.H. Lawrence quote: “The eyes don’t see what the mind doesn’t know.” She took it upon herself to inform minds so eyes could see. She used her platform as a scientist, doctor and educator to craft a fierce indictment of a society and political system rigged from the jump against its members who are poor, brown and marginalized. Telling the story from her personal life and experience, she invites the reader to know her, to know her family and her values. When she talks about Flint’s families, she makes it clear that she believes health and happiness is their birthright as well. The contrast makes the criminality of official indifference even more obscene.

The brilliance of Hanna-Attisha’s book isn’t simply a description of events that led up to one of the nation’s most dramatic whistleblower events. What the eyes don’t see, she writes, is not just lead in the water, but the racism, inequity, heartless austerity policies and bureaucratic indifference that led to the crisis in the first place. The book’s title and central metaphor are taken from a D.H. Lawrence quote: “The eyes don’t see what the mind doesn’t know.” She took it upon herself to inform minds so eyes could see. She used her platform as a scientist, doctor and educator to craft a fierce indictment of a society and political system rigged from the jump against its members who are poor, brown and marginalized. Telling the story from her personal life and experience, she invites the reader to know her, to know her family and her values. When she talks about Flint’s families, she makes it clear that she believes health and happiness is their birthright as well. The contrast makes the criminality of official indifference even more obscene.

What the eyes also don’t see explicitly in Dr. Mona’s book is also richly there between the lines. In reading her book, we get to know her. It is apparent that “Dr. Mona” was able to accomplish what she did because of who she is. Her friends and colleagues knew her to be trustworthy and a person of ultimate integrity. With that knowledge as their basis, they stood together to right a terrible wrong. In her matter-of-fact telling, she presents the facts unadorned and unembellished.

The story of the Flint water crisis broke over the U.S. like a thunderclap—and was heard around the world. In the years since, further research has confirmed that Flint is by far not the only U.S. city with lead and other toxic chemicals in its drinking water.

In January 2021 a judge granted preliminary approval to a $641 million settlement to benefit Flint residents harmed by the contaminated water. Ex-governor Snyder and former Flint Public Works director Howard Croft were each charged with two counts of willful neglect of duty; other officials were charged with crimes ranging from felony counts of perjury, extortion and misconduct in office to misdemeanor counts of willful neglect of duty. Two officials have been indicted on nine counts of involuntary manslaughter in connection with a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires disease associated with water-quality issues.

Both Snyder and Wurfel have apologized to Hanna-Attisha.

Through a combination of corporate and private donations and government funding, Flint has created a number of programs to help Flint’s children, including universal pre-K, literacy and mental health programs, healthcare access and access to good nutrition—assets Hanna-Attisha says she wishes for all children.

More than 200 years ago, after realizing what a fight they’d have to put up to win this country’s independence, America’s founders pledged their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor to the cause. In this fight for the lives of America’s children, Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha did so as well, joining their ranks to become a true American hero.

K.C. Compton

K.C. Compton worked as a reporter, editor and columnist for newspapers throughout the Rocky Mountain region for 20 years before moving to the Kansas City area as an editor for Mother Earth News. She has been in Seattle since 2016, enjoying life as a freelance and contract writer and editor.