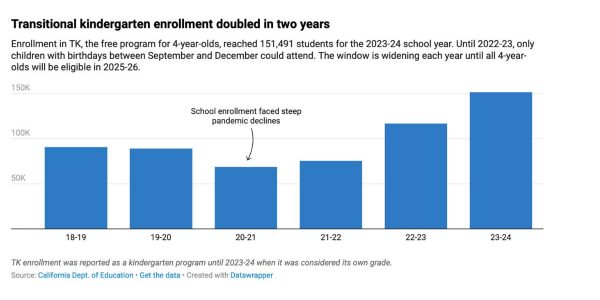

In July, Gov. Gavin Newsom touted the success of California’ transitional kindergarten expansion, saying enrollment in the $2.7 billion program had doubled over the past two years. His comments echoed those of State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, who called the numbers “exciting.”

They both pointed to new data showing that enrollment in the free program for 4-year-olds had gone from 75,000 two years ago to 151,000 last year — a significant recovery after steep declines during the pandemic.

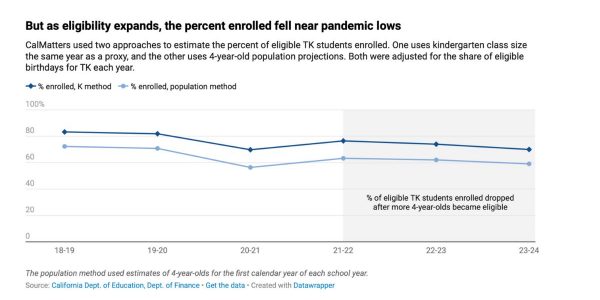

But while the overall numbers are up, the percentage of eligible 4-year-olds enrolled in TK actually fell. As the TK age cut-off widens, the number of eligible children has more than doubled — but the percentage of students who are enrolled dropped between 4 to 7 percentage points between the 2021-22 and 2023-24 school years, depending on how the number of eligible children is calculated.

CalMatters used two approaches to estimate the percent of eligible TK students enrolled: using kindergarten enrollment the same year as a proxy and using general population projections from the Department of Finance. Both approaches show the same trend.

Department of Education spokesperson Elizabeth Sanders said the department uses a method from the Finance Department to calculate the percentage of eligible students in TK but did not provide specifics.

“The trends we see in the percentages of eligible students whose families are enrolling in TK mirror the trends described by (CalMatters’) data set,” she said. “As we expand the number of students and families eligible, we expect the percentage of families who choose to participate to hover around 70% and to increase following full implementation.”

Sanders pointed to the growing number of children attending TK as a hopeful sign for the program, which is intended to boost academic achievement and social skills and prepare students for the rigors of elementary school.

“The fact that we have doubled the number of individual students participating in the program during these implementation years makes us very proud,” Sanders said.

TK advocates said the increased numbers alone are worth celebrating, and they expect the percentage to inch upward over time.

“This is great, this is what we want to see. It shows that schools are building back trust,” said Patricia Lozano, executive director of Early Edge California, which advocates for early childhood education. “TK is a great option for families, but it’s good for kids, too. Kids need to be around other kids.”

Transitional kindergarten was never meant to be an exclusive early childhood service for families; it’s intended to be one option among several the state offers, Lozano said. So any increase in participation is reason for hope.

Transitional kindergarten for all 4-year-olds

The state created transitional kindergarten in 2010, but it was limited mostly to larger districts and was open only to children whose birthdays fell between September and December. In 2021, Newsom expanded it so all 4-year-olds could eventually participate. Rolling out gradually, the eligibility window widens by a few months every year. In 2025-26, all 4-year-olds will be eligible and all districts except charters will be required to offer it.

Research has shown that TK and preschool have many benefits for children, including higher rates of graduation and employment, less criminal activity later in life and overall better health, while parents benefit economically from an extra year of free care for their children.

Transitional kindergarten is meant to be like preschool, a low-key environment where children spend most of their day playing and learning social skills. Typically, children learn to take turns and make friends, express themselves and regulate their emotions, count to 10 and recognize simple words, and learn fine motor skills such as holding a pencil. Unlike preschool, TK teachers are required to have credentials and, by 2025-26, extra units in early childhood education.

Michelle Galindo, a parent in Chula Vista Unified south of San Diego, said she was hesitant at first to send her son Roberto to TK. She’d heard reports of crying children and inexperienced teachers, and 4-year-olds seemed too young for school.

But she happened to know the teacher and trusted her. Her son thrived in the program, gaining independence, making friends and learning.

“He’s so much more confident. He asks a lot of questions, is more responsible,” Galindo said. “When he got to kindergarten last year, he actually thought it was too easy. The teacher said he was a full year ahead. I’m really glad we sent him to TK.”

Wealthier districts slow to open transitional kindergarten

There are a few theories explaining the stagnant percentage of TK enrollment. One is that not all districts are offering it yet. Districts known as “basic aid” districts have been slow to open TK programs, and some aren’t offering it at all. Basic aid districts are typically wealthy districts that opt out of state funding because they collect more money through local property taxes. Because of that, they can’t get state funding to operate TK classes.

Marin County is home to several basic aid districts that have lagged in opening TK programs. Larkspur-Corte Madera School District isn’t offering TK at all, saying it can’t afford to without state help. Ross Elementary doesn’t offer TK, either. The result is that Marin has one of the lowest TK enrollment rates in California, even though the county has pockets of low-income families who would benefit from the free service.

“Everyone thinks TK is a good idea, but for basic aid districts, it’s an unfunded mandate,” said Marin County Superintendent of Schools John A. Carroll. “It’s taken a while, but we’re getting there. Most have now gotten on board.”

San Francisco Unified also has one of the state’s lowest TK enrollments, with more than four times as many kindergartners as TK students. Statewide, there were 2.4 kindergartners for every TK student last year. San Francisco’s low numbers are partly due to the extensive preschool program the district already offers. They’re also due in part to a steady decline in the number of children living in San Francisco, as parents leave for less expensive locales, said district spokeswoman Laura Dudnick.

Facilities have also been an obstacle for school districts. Districts must find space for new TK classrooms, which in fast-growing parts of the state has been difficult. Proposition 2, a $10 billion bond on the November ballot, would provide funding for schools to build and expand TK classrooms.

Preschool vs. transitional kindergarten

Another hurdle to TK enrollment is preschool. In addition to private preschools and federally funded Head Start programs, California offers free preschool to low-income families. Some parents said they prefer to keep their children in preschool because it’s convenient or they like the program.

Roslyn Broadnax, a parent in South Los Angeles, said she distrusts the state’s push for TK, fearing that TK will siphon resources from state-funded preschools, which in many cases are long-established, trusted parts of communities.

“The existing preschool system has served low-income kids, kids of color very well,” said Broadnax, who works for Cadre-LA, a nonprofit that advocates for parents in South Los Angeles. “If there’s little difference between preschool and TK, why should a parent move their child to TK? It doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

A recent report from UC Berkeley found that the TK expansion has had a damaging effect on state preschools and Head Start, as parents move their children out of those programs. Although the overall number of 3- and 4-year-olds enrolled in early childhood education programs has increased slightly, Head Start centers in California have lost 43,000 preschoolers, while state preschools have lost 9,000 4-year-olds since the TK expansion. The result has been shuttered classrooms, a scarcity of teachers and uncertain futures in what researchers called “pre-K deserts.”

“The real question is, are more families accessing pre-kindergarten overall? We can’t find evidence that they are,” said Bruce Fuller, an education professor at UC Berkeley and an author of the study. “To say that the TK enrollment has doubled relative to a year in which many preschool classrooms were closed (due to COVID) is disingenuous.”

Another hitch is that during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when most preschools closed, California guaranteed funding for them through 2025. Now, the state is paying for half-empty preschools across California and preschools have no incentive to recruit more families, according to the report.

The whole early education system in California is overly complex and confusing for parents, Fuller and his team said. They recommend a streamlined, consolidated system that delivers high-quality, play-based programs that are distributed equitably throughout the state.

Not enough qualified teachers

Staffing has been a challenge since the beginning of TK. While most school districts have been able to hire enough credentialed teachers, they’ve struggled to hire classroom assistants and teachers who have the extra credits in early childhood education that will be required by 2025-26. Schools reported a 12% vacancy rate for TK teaching assistants at the beginning of the 2022-23 school year, according to a recent report by the Learning Policy Institute.

Ericka Hill, a parent in Los Angeles, said her son was in a mixed kindergarten-TK classroom, with a substitute teacher for half the year. The substitute had little experience in early childhood education and gave the children worksheets to take home every night.

“I don’t think a 4-year-old should be sitting down at a desk. It needs to be age appropriate,” Hill said. “He was resistant to doing the work. It was difficult for all of us.”

San Diego, Los Angeles, Sonoma, Orange and Ventura counties have some of the highest rates of TK enrollment, thanks in part to extensive outreach to parents. Bus advertisements, billboards, online ads, and flyers at day care centers and preschools all helped bring in new families.

Garden Grove Unified, a mostly low-income district in northern Orange County, expanded its TK program so quickly, in fact, that it incurred hefty fines from the state for allegedly enrolling students who didn’t yet qualify and not meeting student-teacher ratios that the state set later. The district is fighting the penalties, but meanwhile nearly every child who’s eligible for TK is enrolled.

“We knew that our families would want to enroll as soon as possible,” said district spokesperson Abby Broyles. “We launched a marketing campaign to get the word out. … Our families have been thrilled with the high-quality TK they’ve received.”

This article originally appeared at CalMatters.