Early Learning Nation magazine often focuses on child care and early education, which comprise about one-fifth of the $648 billion care economy. Yet care doesn’t happen in a vacuum or only during one period of life. As we age, we need care, and disabled people need long-term supports and services. This election season is a helpful time to take a step back and look at the whole care picture.

Maintaining a holistic view of care avoids characterizing any one type as more or less worthy of public investment so we can forgo arguments about whether seniors or young children are more deserving; the care sector is stronger united than divided.

I spoke to Julie Kashen (director, Women’s Economic Justice and senior fellow, the Century Foundation), Anna Shireen Wadia (executive director, the Care Fund) and Robert Espinoza (CEO, National Skills Coalition) to learn more about other parts of the care sector and what child care advocates should understand.

👉 Transforming Our Undervalued and Largely Unseen Care Workforce (interview with the National Domestic Worker Alliance’s Ai-jen Poo)

These conversations took place before Vice President Kamala Harris became the presumptive Democratic nominee for President and before she named Minnesota governor Tim Walz as her running mate, but Kashen, Wadia and Espinoza’s insights couldn’t be more relevant at this moment. As Jonathan Cohn has pointed out in the Huffington Post, Harris’s personal and political experience indicates firm commitments to child care, paid leave and related issues. Walz has presided over historic public investments in care.

👉 The Data-Driven Case for Care (Pivotal Ventures)

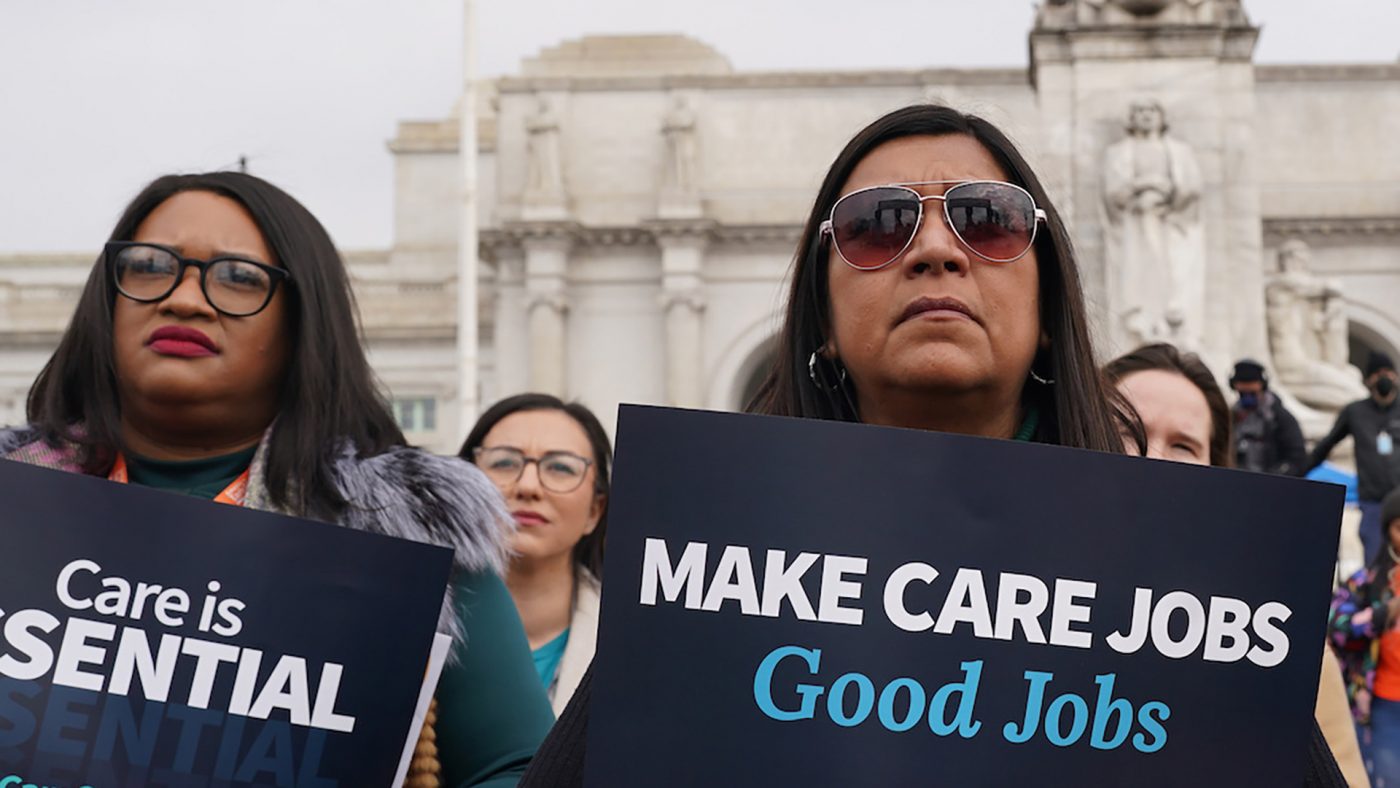

As Kashen observes, the care workforce is mostly female and disproportionately women of color. Low pay and few benefits and protections are the norm. “It’s a challenging sector,” she admits, “but at the same time, many people doing this work really love the work of care and find it’s incredibly rewarding.”

Wadia says care is distinct from other forms of work because of “the intense and intimate relationship between consumers of care and the workers they are entrusting to care for their loved ones.” Don’t forget that while these are economic issues, they aren’t just economic.

👉 Overcoming Occupational Segregation and the Systemic Devaluing of Women’s Work

Compensation: The Bottom Line

Care work makes all other work possible. Unless this challenging, skilled labor pays a living wage, caregivers will continue to defect to retail and customer service. Wadia underscores the irony: “In some ways, this is the most important work that can be done in our society, and yet it is among the worst compensated work.”

Kashen offers a grim if undeniable historical perspective. “Caregiving has long been undervalued,” she maintains. “You can look back to the origins of chattel slavery that forced Black women to nurse and care for the children of white landowners, to the detriment of their own children.” Women of every race and ethnic background have traditionally been the default caregivers for children, disabled loved ones and aging relatives. This free domestic labor has tended to make care undervalued and invisible—cultural norms that need to be challenged forcefully if things are going to change.

“The better you’re able to compensate caregivers,” Kashen states, “the more likely they’re not going to be economically insecure and stressed, so they can be more present with the people they’re caring for.”

While the paycheck is paramount, other factors count, such as respect, predictable hours and a pathway for advancement. Without a clear career ladder, Wadia says, “Moving up generally means moving out.” Early educators apply for jobs in K-12 education, and those caring for seniors seek qualification for nursing and other health care professions. Experts are coming up with ways for these providers to gain relevant skills and credentials that retain them in the sector if that’s where their passion lies.

Espinoza foresees technology altering the economics of care, making the job more efficient and supporting workers—without replacing them. He cautions, “We’ll also need strong policies to ensure tech innovators and businesses are drawing on workers’ expertise to inform this technology and safeguards to prevent unnecessary worker displacement.” Family supports, including child care for care workers as well as public transportation and a more equitable system of benefits, would also make the sector more sustainable.

👉 Care Matters: The A 2024 Report Card for Policies in the States

Advocacy: Caring Out Loud

Writing in The Atlantic around the time her book, Parent Nation, came out, surgeon and advocate Dana Suskind described the gains for U.S. seniors made possible by the AARP. The organization pushed for the Older Americans Act of 1965, and since then has secured prescription-drug benefits and protection of Social Security, among other measures. Calling for a “National Association of Parents and Caregivers,” she declares, “We have the economic case, and the general consensus, that parents need more support. What we lack is political clout. Older Americans galvanized because there was finally someone looking out for them, not the other way around. Parents need a similar revolution.”

👉 Portraits of Care (The Care Can’t Wait Coalition)

Some of this work is already taking place, though not on anything like AARP scale. (The American Association of People with Disabilities also packs a wallop.) Wadia sees potential in advocating for significant public investment. “It’s the only way that we are going to have quality, affordable and accessible care, whether for children or older people or people with disabilities and decent jobs for care workers,” she says.

Kashen similarly recognizes the power of workers and advocates joining forces across the care continuum and alongside the people whose jobs are only possible thanks to the care sector: “Bringing together the consumers of care with the providers of care,” she says, “you have a much stronger conversation, especially with Caring Across Generations, which is now at the center of the Care Can’t Wait movement. We’re all part of the same ecosystem, and we all need the same things.” Hand in Hand, the domestic employers network, is another piece of the advocacy puzzle, she says.

“Care is such a powerful mobilizing and unifying set of issues,” Wadia explains, “because people experience care crises and care responsibilities across income and across race. It has become a unifying issue.”

Organizing: Union-Strong Care

One key difference between child care and elder care can be found in the power of unions. Nursing home workers participate in unions—chiefly, AFL-CIO and SEIU—at greater rates than their counterparts in child care centers, family care and other settings. Membership, as they say, has its privileges, including job security and health benefits.

Although child care workers are a long way from catching up, they are beginning to catch on (especially in California)—and no wonder. As the Economic Policy Institute has noted, “High unionization levels are associated with positive outcomes across multiple indicators of economic, personal and democratic well-being.”

For Kashen, the care sector as a whole advances with policies supportive of organizing and bargaining, especially where providers have government grants or contracts, as opposed to subsidies that go to individual families.

👉 Implementing Care Policy Equitably: Lessons from the American Rescue Plan Act (The Century Foundation)

Thanks to the efforts of SEIU and the National Domestic Workers Alliance, those who care for seniors and disabled people in their homes have gained more traction with organizing. The home, Wadia notes, is a very different workplace setting. “It leads to a lot of challenges for organizing because people are atomized. Employers of home care workers will say, ‘You feel like family to me’—which is often very positive, but it also means that the consumers or the employers don’t necessarily see these as real jobs or see themselves as employers.”

Immigration: Getting the Care Job Done

According to PHI, immigrants constitute at least 27% of workers in “direct care”—which covers working with seniors and people with disabilities—while a 2015 report by the Migration Policy Institute found that 18% of early child care workers were born outside the U.S. (compared to 13.8% of the general population). The percentages may be even greater, Espinoza notes, referring to undocumented home care and child workers in the so-called gray market, but clearly, immigrants make up a significant part of the care workforce, and solutions to chronic problems aren’t viable unless they make sense for this subsection of the labor market.

Espinoza, who formerly served as executive vice president of policy at PHI, says that as the son of a Mexican immigrant, he has a personal interest in “imagining sound and humane policies that support immigrants and support our country’s economy.” He acknowledges that more work needs to be done to help a considerable portion of the American public see the value in federal and state policies that make it easier for even more immigrants to participate in the care sector. “Caregiver visas” might be a solution worth exploring.

👉 Discover Robert Espinoza’s podcast, A Question of Care

In addition to immigrants, Espinoza says older workers and Generation Z men might be engaged to address shortages.

The pandemic made caregivers more visible—their value to families and the gaps and inequities that have persisted for decades. Espinoza points to labor shortages and other trends across the U.S. labor landscape that are buffeting the care sector. “A large percentage of workers are retiring and reducing their hours, and have done so even more since the end of the pandemic,” he says. Looking at new pipelines of people to take these jobs should be a priority.

The big takeaway from these three experts? A thriving, fair economy depends on a robust, equitable care sector—across lifespans and around the country.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.