Imagine you are building a car. You invest in a solid chassis, make sure the wheels are inflated, oil the brakes. A lot of time, energy and money goes into the work, but when the time comes to roll it out of the garage, the car won’t move. Why? Because you forgot to build an engine!

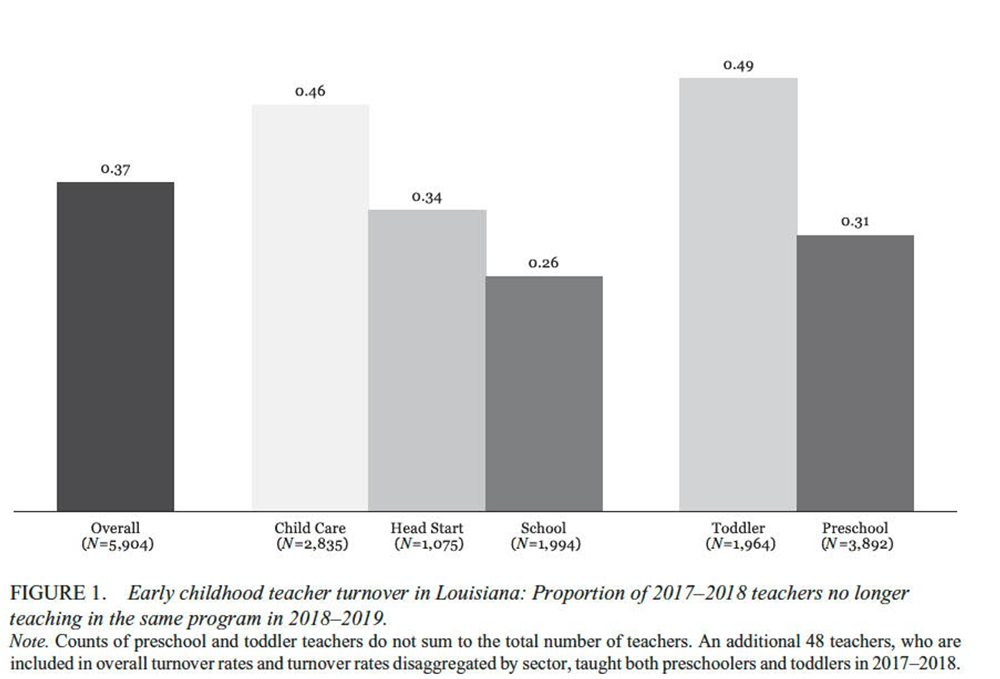

It’s long been known that child care programs experience high turnover, but because child care is delivered in a dizzyingly wide variety of settings, the churn problem has been hard to quantify. Not anymore. A study released in January took advantage of Louisiana’s uniquely robust early childhood data system to take a look under the hood, and what they found was stunning: nearly HALF of child care lead teachers are leaving every. single. year. (This data was collected pre-pandemic.) The crisis is worst for infant and toddler teachers, and it’s not good even for fully publicly-funded programs.

Sit with that chart for a minute. One in two lead teachers walking out the door every year, with all of the attendant problems of needing to recruit and train a replacement —when you can find one — recreate a staff culture and address the disruption to young children who thrive on consistent, reliable relationships. Half of a state’s professional development dollars, poof. For comparison, public school teachers have an average turnover rate of only 16%, and fully half of those are simply moving to a different school.

There are, of course, lower churn rates (though still staggeringly high, in an aggregate sense) among Head Start and school-based Pre-K teachers. The reason why isn’t a mystery: as James Carville might say, it’s the compensation, stupid! Practitioners in those settings have superior, if still inadequate, wages and benefits.

This brings us to the other recently-released report: The 2020 Early Childhood Workforce Index produced by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California-Berkeley. The Workforce Index shows that in 28 states, including Louisiana, the median wage for child care teachers is still less than $11 an hour(!). The national median is $11.65 and has barely budged over the past several years. Target and Amazon, meanwhile, now have national starting wages of $15 an hour. (Kindergarten teachers have a national median of $32.80 an hour, by the way.)

The other part of the equation is benefits. According to a 2015 report, only 15% of child care practitioners receive health insurance through their workplaces, forcing most to rely on spouses, Affordable Care Act exchanges or Medicaid. Worse, in some states, as many as one in five remain uninsured entirely — as one North Carolina child care teacher told NPR about what she would do if she caught COVID-19, “I have no clue. I have a little bit in savings but I’m quite sure not enough to pay for medical bills if I have to be hospitalized.” Again, it is necessary to draw a contrast with other low-wage industries: even retail behemoths like Walmart that have otherwise dubious workplace reputations offer health insurance and retirement plans.

So it comes down to this: Any child care plan that does not start with hugely, massively, tremendously increasing child care teacher wages and benefits is not a credible plan. The goal cannot be to nudge the median wage slowly towards, say, $15 so that child care programs can go up against the Targets of the world. Child care shouldn’t be a low-wage industry to begin with, given the indelible impacts on child development, family stability, and the overall economy. The goal must be to reach credible, family-sustaining wages with benefits for all lead teachers, regardless of the type of program in which they work or the age of the children they serve.

One way to do this would be to peg the goal to the median Kindergarten wage (although “pay parity” brings baggage around degree requirements and over-applying K-12 frameworks). Other high bars will do: British Columbia’s “$10 a Day” plan sets the goal of a $25/hour wage floor plus 20% in benefits. Since these plans would basically double or triple the current median wage, you can understand why they may be considered rather ambitious. I reject that idea: in light of the harrowing turnover rates, reasonable compensation is not so much ambitious as a prerequisite for an effective system.

The fact is there is no high-quality child care system without a sustainable workforce. There’s an ongoing debate about what exactly defines quality for a child care program, but no one doubts quality starts with secure and lasting relationships between caregiver and child. While there is little concrete data due to the difficulty in tracking teacher movements, research suggests that “continuity of care” is particularly important for infants and toddlers, and that multiple caregiver changeovers can lead to negative child outcomes. As Bassok said, this makes it all the more worrisome that infant and toddler teachers are the group with the single highest churn rate. (Even for those who stay, being highly stressed out due to financial precarity is a recipe for distraction.)

So as policymakers turn their attention from salvaging the existing child care system to building one that works, the first-order question must be: How do we get enough public money flowing annually into the sector to allow wages to rapidly rise? Affordability is important, of course, and cost is likely the window through which to communicate with the general public and build political will. But lowering out-of-pocket costs for parents without putting a rocket booster on wages is inviting folks to use our shiny car without mentioning they are going to need to get out and push.

Nearly one in two child care teachers leave their program every year. Almost all of those leave the profession entirely. Those two facts need to be seared into stakeholders’ minds — and then we need to act.