Never underestimate Fred Rogers.

With his cardigan, close-cropped hair and soft voice, it’s easy to imagine that the kind and gentle Mister Rogers belongs to a bygone era. Yet he never did quite fit in. The children’s television icon premiered in 1968, a year that saw the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. as well as intensified protests against the war in Vietnam. Even in a show aimed at youngsters, kindness and gentleness stood apart from the times.

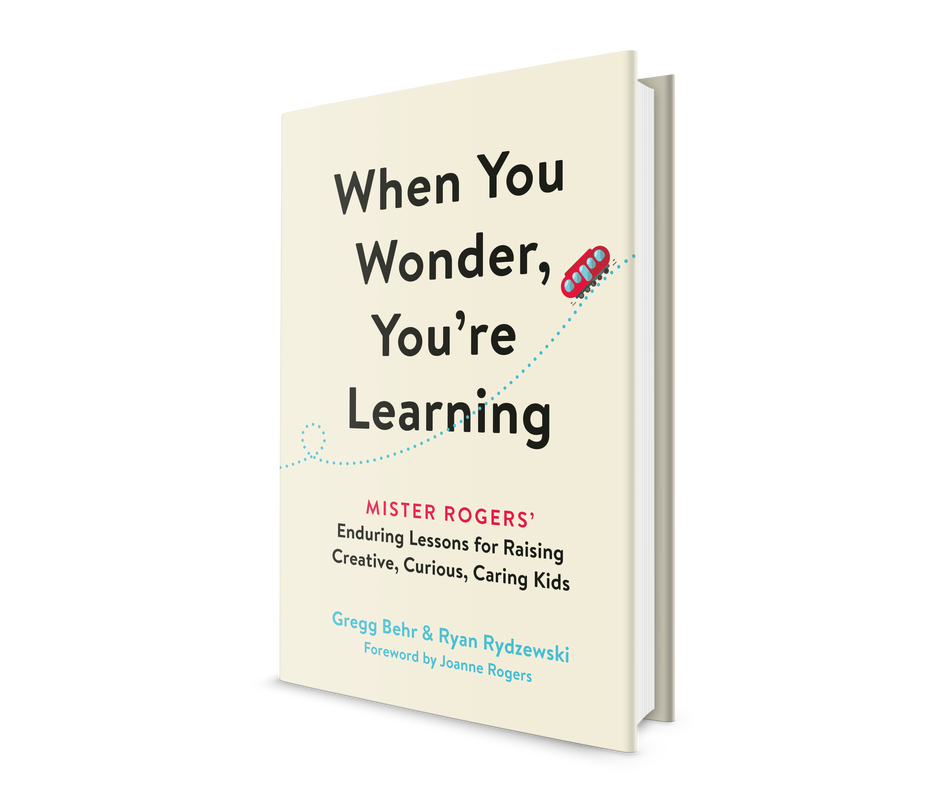

A new book, When You Wonder, You’re Learning, shows that these qualities never go out of style, in part because they never have fully taken hold. Gregg Behr and Ryan Rydzewski not only make the case for Fred Rogers’s genius—we’ll come back to that word—but for his continued relevance today. He set a lofty but attainably homespun example for parents and teachers that continues to light the way nearly two decades years after his death. “Who better to turn to when kindness seems lacking than the kindest person we’ve known?” asks Joanne Rogers in her foreword.

👉 Fred Rogers: Seeker of Truth, A Personal Reminiscence

This isn’t a standard text on bringing up children. (The word discipline appears only once; love and loving appear dozens of times.) Joanne Rogers’ foreword calls it “the blueprints my husband left us”—the blueprints for enabling kids to discover the finest adults they might become, and helping them fulfill their purpose. Follow these blueprints and children can grow up to be, in Behr and Rydzewski’s words, “people who can build stronger, more inclusive communities and a more just and loving world.”

Although it serves as blueprints for raising children anywhere, When You Wonder, You’re Learning is, like the man who inspired it, a proud product of Pittsburgh. The authors both live in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, so to speak. (Behr, director for the Grable Foundation and founder of Remake Learning, advises the Fred Rogers Center.)

Mister Rogers—and this book celebrating his vision of child development, still matter for all of us—parents or not. The subtitle points to three landmarks along a journey from childhood to adulthood and from a broken society to one that lives up to our highest ideals.

- Creativity. We aren’t just talking about the Magic Marker drawing stuck to the refrigerator. Defined here as “the ability to generate new ideas and synthesize existing ones,” creativity is the most vital way to approach life and one another, and the authors cite Barack Obama, LinkedIn and others to show its value to society. Human beings, Behr and Rydzewski note, are born creative. Children instinctively make “illogical” connections and expect stories to veer in unexpected directions. Yet creativity is a fragile commodity that can drain away as early as fourth grade.

The authors quote a warning from Mister Rogers: “What happens if children hear that their mud pies are no good and their block buildings have no importance? That their paintings and dances, and made-up games and songs, are of very little value?” This grave scenario might be coming into existence. Research by Kyung Hee Kim and E. Paul Torrance indicates a growing creativity crisis. The book highlights thinkers (including Kathy Hirsh-Pasek and Roberta Golinkoff) and institutions (such as Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library) putting into practice insights for nurturing and sustaining creativity.

- Curiosity. In a world where technology promises an app for everything, the man the authors call “curiosity’s most famous televangelist” reminds us that learning comes down to asking and answering questions. “Given ample opportunities and encouragement,” Behr and Rydzewski, write, “kids will ask questions about just about anything.” Unfortunately, home and especially school can sometimes squelch their natural curiosity, as adults focus on their own priorities and curricula.

The authors highlight “a disconnect between what kids naturally do (ask questions that interest them) and what they actually do (work within the confines of an adult’s plan).” Wonder isn’t about spacing out. It’s about finding our own way to connect to the world around us. Adult-driven certainty—the opposite of wonder—is inhospitable soil for curiosity, and adult-driven agendas often crowd out this seemingly aimless but actually critical activity. The solution is as simple as it is maddeningly elusive: unhurried, open-ended conversation.

- Caring. Bill Strickland, founder of the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild in Pittsburgh and a frequent guest on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, stresses to the authors that the host was “always And he demonstrated by his life that no matter how you look or where you came from, you were a member of the Neighborhood. That’s the reason I built this place: I wanted to give kids that same feeling. I wanted to be Fred Rogers.” (Read more about Strickland.)

In the vision of kindness espoused by Mister Rogers and celebrated in this book, kindness is considerably more than not bullying. It’s an active, inclusive pursuit—a cornerstone of citizenship. Of course, we all want our children to be nice to their sibling and classmates, but the times demand an expansive definition of neighborhood. They demand that we instill what the authors of a recent University of Washington study call “identification with all humanity.”

Fred Rogers was nothing if not humble, and, true to his spirit, this book doesn’t dwell on his considerable gifts as a media visionary or education innovator. It adheres to the idea that he was one of us.

As the authors explain, “No one in the Neighborhood is a ‘natural’ or a ‘genius.’ Some might have aptitudes for one thing or another, but their worthwhile achievements always come down to effort.”

But if they won’t say it, I will. The man was a genius—all the more so because of his humility. He embodied and espoused a revolutionary vision for living in a neighborhood as big as the planet.

👉 Read more: Lessons from the History of Children’s Television: The Original Distance Learning

When You Wonder, You’re Learning: Mister Rogers’ Enduring Lessons for Raising Creative, Curious, Caring Kids

Gregg Behr and Ryan Rydzewski

Foreword by Joanne Rogers

New York, NY: Hachette Books, 288 pp.

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.