When Jack Shonkoff speaks, the early childhood field listens. Shonkoff, a pediatrician who leads Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, is one of the researchers who brought about the brain science revolution in understanding child development. Among other accolades, he chaired the committee that wrote 2000’s groundbreaking report, Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. So when Shonkoff recently released a call to action to advance the way early childhood stakeholders engage with the world, it is cause for deep consideration and reflection.

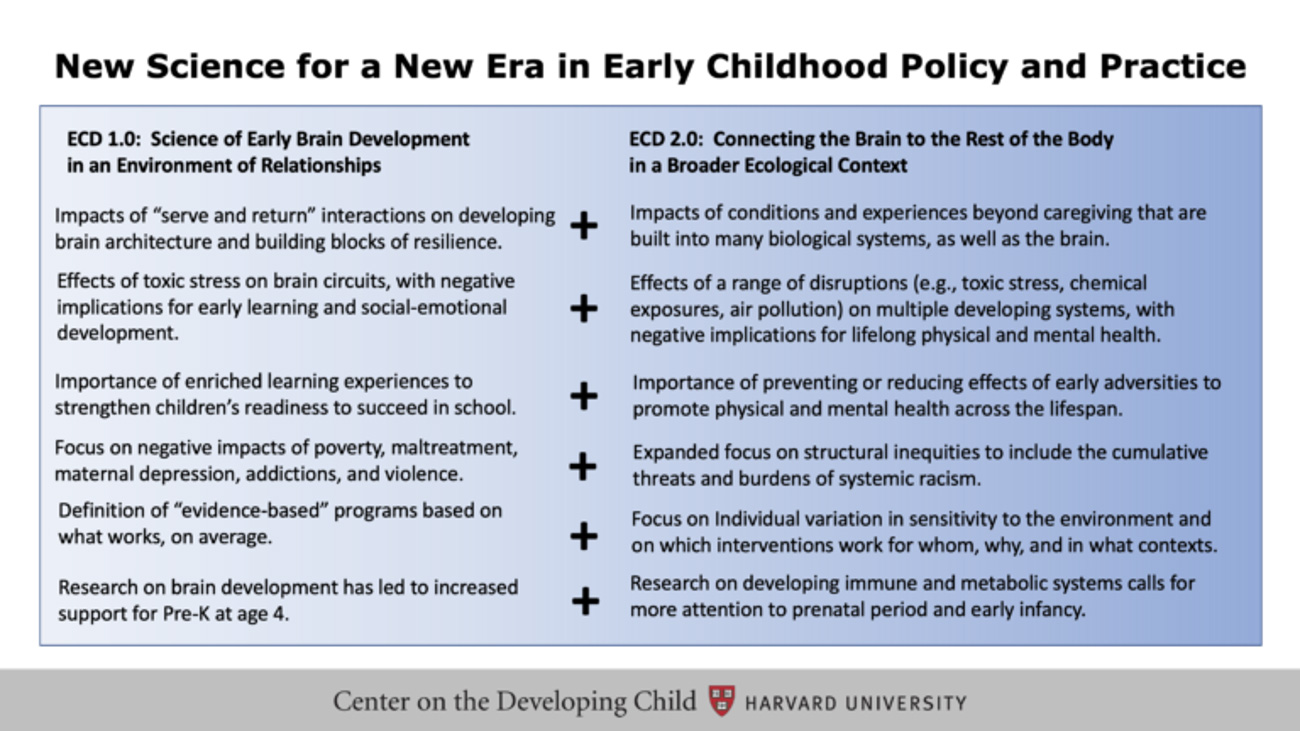

Shonkoff’s statement is called “Re-Envisioning Early Childhood Policy and Practice in a World of Striking Inequality and Uncertainty,” and bears the subtitle “New Science + More Diverse Voices = Greater Impact.” His overarching point is that the existing circumference of early childhood development – – what he considered early childhood development or ECD “1.0” is absolutely correct, but drawn too narrowly. The way to build on these foundations, Shonkoff offers, is by embracing contemporary science around the interaction of a child’s body and surrounding environment—including exposure to literal toxins and structural inequities —with their brain development. He calls this both-and perspective “ECD 2.0,” and writes (emphases his):

- It’s still about the brain and it’s also about immune and metabolic systems.

- It’s still about readiness to succeed in school and it’s also about lifelong health.

- It’s still about the hardships of poverty and it’s also about the threats and burdens of racism.

- It’s still about nurturing relationships and it’s also about building a health-promoting society.

In my view, what this implies is that the early childhood field needs to further break down its silos. It should be said that, to its credit, compared to nearby fields like K-12 education, early childhood is already much better at taking a true whole-child approach; so there are certainly places where this is already happening. Child care policy, paid leave policy and home visiting policy—whereby a trained professional provides support to new parents—tend to be cousins, related yet distinct. Maternal and child health policy, such as access to doulas, can be another step removed. An ECD 2.0 lens suggests these are in fact inseparable parts of the same immediate family and should be treated as such.

ECD 2.0 also says that issue areas currently considered far afield from early childhood must be drawn closer in our metrics, advocacy, and philanthropic investments. Young children, it turns out, have gravitational pull: they bring a multitude of satellite priorities into orbit. For instance, mold and lead abatement are generally the purview of the housing sector, but given the impacts of environmental toxins on developing bodies and brains, early childhood stakeholders may need to join forces on a housing quality agenda.

Climate change is perhaps the most striking example. Shonkoff mentions air pollution, one of the more vicious environmental threats to children supercharged by climate change. With large swaths of America on fire for large portions of the year (witness December’s devastating Boulder County fire and the one currently raging in Big Sur, California), and air pollution trapped by heat, this is not a matter of small concern. And air pollution is only one of a rogue’s gallery of climate-enhanced dangers to which young children are uniquely vulnerable. Again, ECD 2.0 demands an early childhood response to the climate crisis. (For what it’s worth, this should not be a one-way street: other fields need to embrace and invest in young children with far more alacrity than they currently do.)

What’s particularly stirring about Shonkoff’s call to action is that he is not asking the field to abandon its fundamentals, but instead to acknowledge both the value and limitations of those fundamentals along with the need to evolve. As he concludes: “The early childhood field is at a critical inflection point in a changing world. The opportunity to align new science and the lived experiences of families and decision makers across a diversity of sectors, cultures, and political values offers a powerful pathway forward. The need for shared leadership along that path is urgent.”