Originally published by The 19th; republished here with permission under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

On Monday afternoon, a friend who works at the local Walmart sent Breanna Dietrich the message she had been waiting three months to receive: The store was about to restock the exact baby formula she needed.

Come quick, the friend told Dietrich. She wasn’t allowed to hold it for her.

The stay-at-home mother of five threw together a diaper bag and grabbed her 10-month-old daughter. Her other four kids, who were walking home from school when she got the text, jumped in the van with her for the 15-minute drive to the store — one of only two where parents can get formula in Wheeling, a West Virginia town near the Ohio border. She was about a week and a half out from running out of formula entirely.

As Dietrich drove, she thought of the hundreds of families in the rural area where she lives — including her own — who are clamoring for any can of formula they can get. She runs a Facebook page that has amassed more than 840 members in just three weeks, many of whom are low-income parents trying to find formula amid a severe national shortage. She posted to the page before she left home to alert them.

By the time Dietrick reached Walmart, only 20 minutes had passed since the formula had hit the shelves. There were two cans left. She picked them both up.

Others congregated in the aisle. A grandmother who was trying to find formula for her two grandsons who had just left the neonatal intensive care unit had just picked up her cans. A dad who had seen the post on the Facebook page had arrived just minutes too late. One of Dietrich’s sons took a can out of their cart and handed it to him. The dad had been to five stores across dozens of miles and had yet to find a single can of formula.

They all recognized Dietrich’s shock of fuschia hair from the page and thanked her for letting them know. Children would be able to eat because of this.

“Seeing some of these parents… staring at empty shelves that I know have been empty for weeks … seeing that they can’t hold their shoulders up anymore because they’re probably on their last bit of gas in their car, because they’ve gone to every store they can think of — I can’t take these broken hearts everywhere,” said Dietrich, 35. “I know how it felt for me when I walked into the store and I found one can of her actual formula. You could have told me I also found $1 million, and I don’t think the feeling would have been different.”

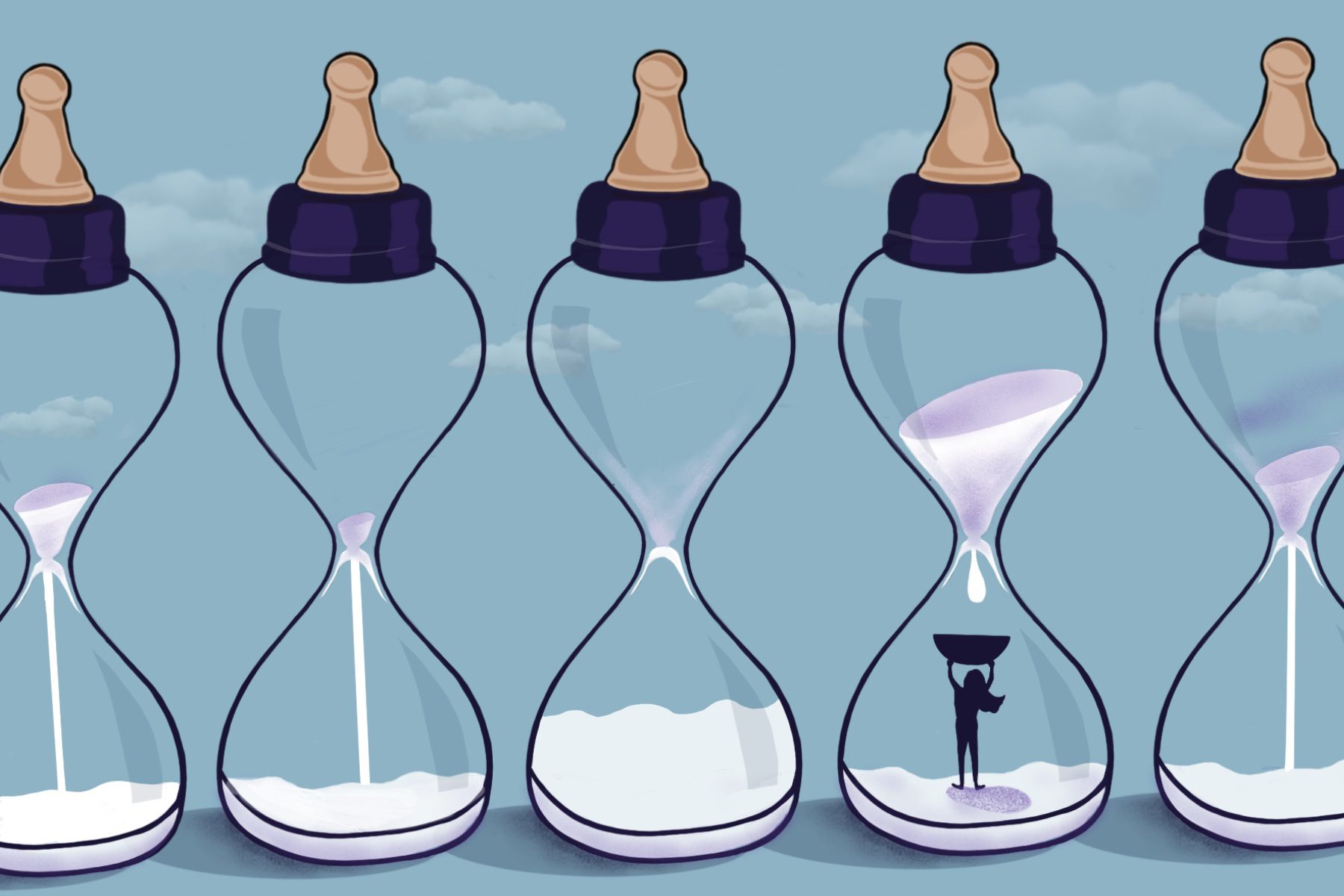

The infant formula shortage that began earlier this year has reached a boiling point in recent weeks. It’s being felt acutely in rural parts of the country. When there are only one or two grocery stores in town, and when filling up the tank to drive from store to store to find formula — as many parents have been doing for weeks — is an economic impossibility, the need reaches a degree of intensity that is potentially life-threatening.

More than 40 percent of all formulas are out of stock across the nation — as much as 20 times worse as it was in early 2021 — due to pandemic-related supply chain issues and a formula recall in February that closed the major Abbott Nutrition production plant in Michigan, the biggest in the country. Abbott, one of only a handful of manufacturers, is the largest supplier of infant powder formula in the country, accounting for 42 percent of the market last year.

This week, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced it had reached an agreement with Abbott that would likely see the plant restarting production in two weeks. But the impact won’t be felt for another two months.

Low-income families, most of which are headed by women of color, are experiencing the worst of the shortage. They are more likely to feed their babies formula in part because they don’t work in jobs that allow them the flexibility to pump or breastfeed.

As many as 65 percent of all formulas in the United States are purchased by families through WIC, the assistance program for low-income women and children, according to data from the National WIC Association, the nonprofit advocacy group for the program. About half of all babies on WIC use Abbott formulas, which include Similac, Alimentum and EleCare.

In rural swaths of the country, families are more likely to be living in poverty, more likely to be on WIC, more likely to face transportation barriers and less likely to have access to the retailers that carry baby formula.

In rural Alabama, a coal miner auxiliary union president, Haeden Wright, said it had been three weeks since the union was able to find any formula for member families who need Enfamil’s Gentlease for children with sensitive stomachs — the same harder-to-find label Dietrich was looking for when her Walmart finally restocked.

Wright is the president of two locals representing spouses of the United Mine Workers of America union members, who have been on strike for more than a year trying to reverse a series of concessions workers say were forced on them during the company’s bankruptcy in 2016. Because of the strike, parents don’t qualify for federal benefits, including unemployment insurance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), also known as food stamps, unless they already qualified for SNAP prior to the strike.

Where Wright lives in West Blocton, a town of about 1,200, the Dollar General doesn’t carry formula, and the other two stores in neighboring towns, each about 20 minutes away, have been out of stock for weeks.

Union members, who run a pantry for families in need, have been resorting to driving as far as Birmingham, nearly an hour away, to search for formula. The situation is reaching a point of desperation, Wright said. Families in her area disproportionately rely on formula because their jobs don’t provide accommodations for workers to breastfeed, she said.

“I don’t know of any places in Alabama that have a room dedicated for [breastfeeding],” said Wright, who also works as a high school teacher. “A lot of jobs in Alabama are still at the federal minimum wage. So if you’re making $7.25 an hour, you can’t afford to get on a bidding war on eBay, where it’s over $50 for the formula for your baby for a week.”

Often the few options that are left in the store aren’t even covered by WIC, she said.

The way the program is structured, states select one manufacturer through competitive bidding to be covered by WIC. In most cases, it’s Abbott, followed by Reckitt Benckiser — which merged with Mead Johnson, the maker of Enfamil — and Gerber. Those three companies have held all the WIC contracts for three decades. Alabama’s contract, for example, is with Mead Johnson.

In a normal year, parents wouldn’t have much trouble finding the brand covered by their state’s WIC contract, but during the shortage, the tubs that are left are often those that aren’t covered at all. They also can’t purchase formula online using WIC because the program only covers in-store purchases, so they are at the mercy of a local store having the item in stock.

And funds don’t roll over to the next month. Dietrich, the mom in West Virginia, hasn’t been able to use her WIC funds for three months.

Families also can’t use WIC across state lines. Dietrich lives about 5 miles from the Ohio border, where she could try more stores to find the formula she needs. But she wouldn’t be able to use WIC to pay for it; she’d have to use her SNAP benefits. With food and gas costs already on the rise, that’s less money for other essentials.

“I need [SNAP] to feed my other children,” she said.

The White House announced late last week that it was urging states to provide additional flexibility around WIC, allowing parents to purchase any formula that is in stock with their WIC allotment in the coming months. By Thursday afternoon, the House and the Senate passed a bill that would give the Department of Agriculture the flexibility to ease requirements on what types and quantities of formula can be purchased through WIC during a public health emergency or supply chain disruption. It now heads to President Joe Biden’s desk for his signature.

Abbott’s production is set to restart in two weeks, and more formula is coming in from abroad. Biden on Wednesday directed the Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to use Department of Defense commercial planes to fly infant formula to the United States that meets comparable safety standards, bypassing typical — and longer — air freighting routes. The FDA is also relaxing rules on international formula imports to get more formula on U.S. shelves, but that effort could also take weeks to reach consumers.

Abbott also plans to fly in more formula, and other manufacturers are expanding production. Reckitt, the second-largest formula provider, said it has increased production by 30 percent in recent weeks, with plants running even on Sundays to get more formula out. Gerber, which has also ramped up production, said it plans to fly in more formula.

But for now, the shortage is still impacting daily life. For some parents, it’s hard to ignore the link between the empty shelves and the raging debate over abortion access, as well as the series of potentially historic family-related policies that Congress has considered over the past two years.

The United States ranks near the bottom of the list among developed countries for its child care policies and is one of only a handful of wealthy countries that doesn’t have a federal paid leave policy. A proposal to introduce a federal program on both those topics that seemed to have significant support in Congress stalled and is now unlikely to pass.

Kristin Rowe-Finkbeiner, the executive director of MomsRising, a nonprofit advocating for more robust caregiving policies, said the formula shortage is a reflection of the country’s deprioritization of caregiving, work that is dominated by women and women of color both at home and in the workforce.

“In our country right now we tend to look at this as the failure of the person, of the individual, of the mom, not being able to do it all,” Rowe-Finkbeiner said. “But when this many people are having the same type of crisis, when this many people are experiencing the inability to find infant formula, when this many people can’t have access to family medical leave, we have a national structural issue that we can solve together and not an epidemic of personal failures.”

And then there is the abortion debate. In rural parts of the country, where poverty is higher, abortion access is more limited and where more Americans oppose access to the procedure, it’s even murkier.

The Supreme Court is set to release a final ruling soon in a case that could eliminate abortion protections decided in Roe v. Wade, the seminal 1973 case. A draft of the court’s majority opinion leaked earlier this month indicates it intends to reverse Roe, putting the choice of restricting abortion in the hands of states. Some of the states with the most severe formula shortages, including Texas, Tennessee and Missouri, are severely restricting abortion access or plan to do so.

“This is about choice and who has the choice,” Rowe-Finkbeiner said. But too often, she added, there is not a real choice “because we don’t have a care infrastructure in place.”

Taylor Shelby, whose 9-month-old son relies on formula, said the stress of the past few weeks has dredged up the abortion debate for her.

“I don’t necessarily support abortion, but I can still understand … I’m not judgmental towards anyone that chooses that because if you are pregnant right now and you find out you’re pregnant today as a shortage is going on — that’s scary,” Shelby said. “They expect all of us to have these babies and reproduce and they don’t even have the necessary things we need for mothers to take care of our children.”

Shelby, 21, is living in a shelter in Minot, North Dakota, with her boyfriend and son. She doesn’t have a car, but she’s spent the past few weeks getting rides from friends or paying for a cab when absolutely necessary to go store to store looking for her son’s formula, Enfamil’s specialty formula for babies with acid reflux.

She’s had some luck only because the shelter where she lives has been able to provide formula. But even nonprofits that work with women and children are struggling.

Project Bee in Minot, which runs the Dakota Diaper Pantry, is getting calls daily about formula, said Calla Abrahamson, the program director. Project Bee also runs the emergency shelter where Shelby lives.

“Most of them are on WIC, which makes it even more complicated because it’s not like you can order it — you have to be able to go to the store and get it.”

The closest city to them is Bismark, 110 miles away.

“Some of those people don’t have the option to go anywhere to get other things,” Abrahamson said. “Some of them are starting to panic a little bit.”

For moms like Shelby, the past few weeks have been made up of patching together a couple of days of formula at a time — before that panic sets in again and again. Promises of a long-term solution haven’t reached them.

“I’m losing hair, honestly,” Shelby said. “But I’m maintaining because I have to — I have a kid and he depends on me and my wellbeing, so I have to stay sane.”

Chabeli Carrazana is the economy reporter for The 19th. Previously, she worked as a business reporter for the Miami Herald, where she covered the tourism industry, and the Orlando Sentinel, where she covered NASA, the private space industry and labor issues.