This November, New Mexicans sent a resounding message to their state officials: fund early childhood education.

With 70% voter approval, Amendment 1 changes the state constitution to guarantee a right to child care and early education. That promise includes siphoning around $150 million a year from New Mexico’s Land Grant Permanent Fund, which generates billions of dollars from the state’s oil and natural gas fees, toward early childhood education.The fund already allocates 5% of its revenue to the state’s public schools, hospitals and universities. Now an additional 1.25% will fund early childhood education.

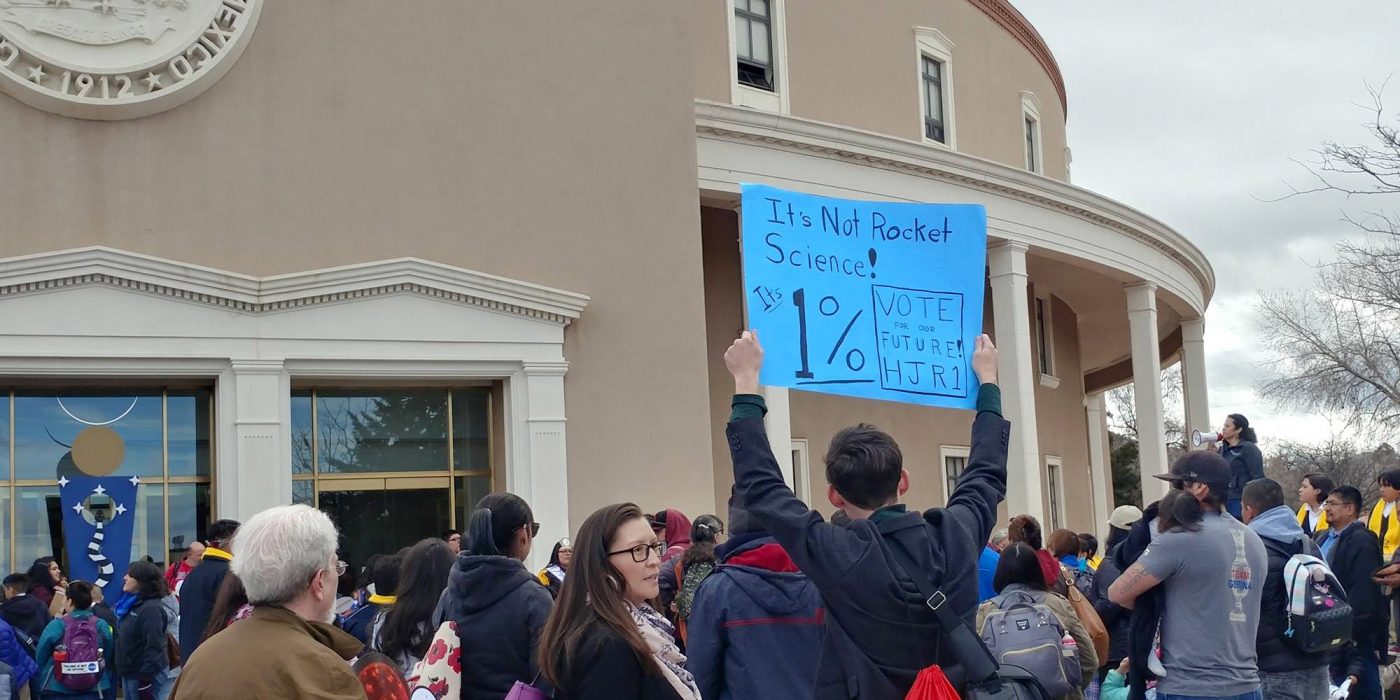

While an overwhelming majority of voters favored the amendment, early childhood education advocates in New Mexico fought a decade-long political battle just to get the measure on the ballot in the first place. This success is credited to a decade of advocacy, community organizing, electoral work, partnerships and alliances, a One Thousand Kid March and “circle-time sit ins.” It was heavy lifting.

New Mexico’s constitution can be amended if a majority of voters approve of the amendment by ballot measure. But before that question can be put to voters, it must first gain a majority vote by legislators in both the state house and senate. That proved challenging for advocates like Andrea Serrano, executive director of OLÉ, a progressive nonprofit based in Albuquerque that has advocated for workers’ rights, fair wages, paid sick leave and early childhood education.

“I think that there were long-time, very powerful senators who practiced the politics of austerity,” she said. “They did not think that expanding the permanent school fund was something that they were going to allow to happen.”

Serrano’s colleague, OLÉ Education Fund executive director Matthew Henderson, had tried engaging in direct action by disrupting committee hearings. But OLÉ and other progressive organizations in New Mexico only found success after primarying the state politicians who had blocked the measure from passing out of the legislature.

OLÉ teamed up with left-leaning activist groups including the New Mexico Working Families Party, the Center for Civic Action and ProgressNow New Mexico to form No Corporate Democrats. The group’s fiat during the 2020 election was to unseat then-state Senator John Arthur Smith, who had chaired the Senate Finance Committee. The southwest Democrat once described the proposed fund distribution as “fiscally irresponsible.” The measure passed six times on the House side but Smith killed it each time it entered his committee.

No Corporate Democrats also targeted Senate pro tempore Mary Kay Papen, Senate Corporations Committee Chair Clemente Sanchez, Indian and Cultural Affairs Committee Chair Gabriel Ramos and Senator George Muñoz. The progressive group was successful in unseating all but one senator, Muñoz, who took over Smith’s former chair and approved the ballot measure legislation in 2021.

“Ultimately only one thing really changed things,” Henderson said. “Continuing to organize and build enough political power that we, as part of the coalition, unseated John Arthur Smith in the Democratic primaries in 2020 and four other powerful senators: the Senate pro tempore and in the Senate Corporations Committee chairman. And, by removing these obstructionists, we were then able to pass the constitutional amendment out of the legislature the following year.”

Erica Gallegos is co-director of the Child Care for Every Family Network, a national network of community organizations like OLÉ and Family Forward Oregon, as well as larger organizations like the SEIU and AFL-CIO. Before Gallegos was looking at how to replicate New Mexico’s success in other states, and possibly the federal level, she worked on labor organizing in New Mexico and fought to get the constitutional amendment on the ballot.

“It really took community organizing going into the community, talking to folks, organizing with parents and providers to build power across the state and really change the narrative on child care in the legislature and to really make it a top priority,” Gallegos said.

The electoral work to replace the Democrats who blocked the amendment went hand-in-hand with advocacy work, Gallegos added. OLÉ joined a coalition called “Invest in Kids Now” that pushed for the amendment. Its members included home visitor providers, churches and social justice organizations.

In an effort to persuade legislators, early childhood education advocates took their classrooms to the state capitol. In 2020, advocates bused in hundreds of children from across the state for the One Thousand Kid March in Albuquerque to demand funding for early childhood education.

“Oftentimes child care providers would invite legislators to come into their classrooms to see that children are learning, that it’s not babysitting, and sometimes folks wouldn’t show up,” Gallegos said. “So one year we did what we called ‘circle time sit -ins’ where child care providers and the children would go and in different places in the Roundhouse [the state capital] and just hold a circle time like they would in their classroom.”

Early childhood advocates in New Mexico may have a unique advantage over other states when it comes to finding funding for their program; the land grant fund is the third largest sovereign wealth fund in the country. Jennifer Wells, director of the economic justice team at Community Change, a national progressive community organizing group, understands that while not every state has such a generous land grant, New Mexico’s grassroots organizing can still provide a template for other states.

“What does it look like to amend your state constitution to actually include the early years of education? What does it look like to construct an early childhood trust fund that can capture unspent state dollars, growing that over time and that being a dedicated, stable funding source?” Wells said. “What does it look like to have a department that is actually overseeing early education and care funding in dollars?”

The path at the federal level

Since 2020, Early Learning Nation has highlighted the early learning work in New Mexico in 38 articles. Read them here.

At the federal level, funding for universal pre-K faces a tougher road. Shortly after President Joe Biden unveiled his $1.8 trillion American Families Plan in April 2021, a Morning Consult/Politico poll measured public support on the spending measure and found that 63% of voters supported free preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds. The same poll found that 64% of voters supported another provision in the plan that would guarantee that low- and middle-income families pay no more than 7% of their income on child care.

But by the time Congressional leaders negotiated the Inflation Reduction Act this summer, universal pre-K and lower child care costs fell on the chopping block.

“We only came up short on the federal level by a couple of votes and that did not deter us,” Wells said. “What we know is that we’re still moving for a federal win. When we don’t necessarily get that, we fall back in with our partners and talk about what can happen on the state and local level to keep momentum going.”

Despite approval from a majority of voters, the current Congress seems inhospitable toward any bills promoting federal support for child care. The cuts in the Inflation Reduction Act marked the ninth time in less than three years that Congress removed measures in a bill aiding women and families, according to a CNN analysis of data from the Congressional Budget Office and Congressional Research Reports.

“Anyone who believes that this can be done without real political power behind it is going to be disappointed,” Henderson said. “Just the fact that child care wasn’t ultimately included in the Inflation Reduction Act is another example of how child care still doesn’t have the political power behind it yet to become a top priority.”

Gallegos argues that even after the success of the New Mexico’s ballot measure, the state needs additional funding from the federal level to support early childhood education. She noted that in 2022, Governor Lujan Grisham expanded free child care eligibility to families earning up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level, roughly $111,000 a year for a family of four. The latest U.S. Census data shows that at least 18.4% of New Mexicans live below the poverty line. New Mexico ranked 50th in the country for overall child well-being, according to a 2022 ranking compiled by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The same ranking found that 56% of children between the ages 3 and 4 did not attend school.

“We’ve estimated that New Mexico needs an additional 400-500 million dollars annually to fund universal, high quality, early childhood education,” Henderson said. “So, New Mexico is still going to have the need for greater federal investment to really build the kind of child care system we all want. But with passage of the constitutional amendment we’re a lot closer to that goal.

Leigh Giangreco

Leigh Giangreco is a journalist who has chronicled everything from the catastrophic failure of the Pentagon’s most expensive fighter jet program to why Joe Biden is on Tinder. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Politico, Washington City Paper, Citylab, Washingtonian, Eater Chicago, and more.