Charnae Easton knew she wanted to breastfeed her daughter. Even when she was pregnant and requesting accommodations to her mail route, she informed her employers at the post office that she would need a place to pump milk when she returned from leave. She’d even planned to work up until she gave birth, because her contract position with the United States postal service didn’t qualify for paid maternity leave.

But for Easton—and so many women around the country—things did not go as planned. She suffered postpartum depression, which made her return to work difficult. And when she did return and ask for reasonable accommodations for pumping breast milk, she was directed to pump in her supervisor’s office, in front of a window overlooking the main room, in plain view of other mail carriers.

Easton complained, but still used the room, keeping her back to the window. When her route changed and she switched offices, she made the same request: she needed a place to pump milk. “My shift started at 7:00 a.m.,” she explained. “By 1:00 p.m., I really needed to pump.” Her supervisors suggested she pump at Target or in the post office bathroom, and finally her supervisors gave her the option to pump in the basement.

I first interviewed Charnae Easton for a piece in Working Mother Magazine, published in 2021 before the magazine closed down (Working Mother no longer has online archives available). Easton had been right to push her employer to make reasonable accommodations – both for pumping and while pregnant on her mail route. She received compensation for their wrongdoing. But at the time, there still were not federal laws to protect pregnant and breastfeeding women for reasonable requests, including a location to pump breast milk.

Until now. In an 11th hour move as part of the $1.7 trillion end-of-year omnibus spending bill, Congress included language that closes gaps in current law through the PUMP Act, guaranteeing space, time and privacy for nursing workers in all jobs. Prior to the passage of the PUMP Act, an estimated 13 million women of working age were excluded from current nursing mothers’ provisions. Like Easton, their only recourse would be to have a sympathetic supervisor, or pursue legal action. In addition, the omnibus included the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA), a measure to allow pregnant people the ability to request reasonable accommodations at work. This can include anything from carrying a water bottle, taking breaks, allowing a cashier to sit in a chair instead of standing, or be exempt from carrying heavy items. As my Better Life Lab colleague, Vicki Shabo, explains in her Opinion piece for CNN: “This is a right other people with temporary physical limitations have had for years.”

PWFA and the PUMP Act were created to close a loop in the two pieces of federal legislation tasked with protecting the basic rights of pregnant women – the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) and the Americans with Disabilities Act. In 2012, Dina Bakst of A Better Balance, a national legal advocacy organization, spelled out this problem in a New York Times op-ed: those two laws, as written, did not allow for accommodations in the workplace, since pregnancy itself is not considered a disability. After the 2015 landmark Supreme court case, Young vs UPS, accommodations for pregnant women would be required, but only if the pregnant woman could find someone in their workplace with a comparable situation.

Researchers at A Better Balance began tracking what happened to pregnant women who sued their employers. Through their legal analysis, they found that overwhelmingly it was the lack of a comparable employee that meant pregnant women were denied accommodations and lost their case. “The standard was not working under PDA and workers were losing out,” said Sarah Brafman, the national policy director at A Better Balance.

A Better Balance, along with PWFA coalition co-chair groups—the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Women’s Law Center and the National Partnership for Women & Families—began growing the coalition of people calling for a change to the law. Momentum grew on the state level, with 30 states and 5 localities passing their own version of PWFA. But an unusual ally appeared in support of the legislation – business owners and Chambers of Commerce. “These gaps in the law meant that there was a lot of confusion for employers, and it led to litigation and conflict – expensive conflict. They wanted and needed clarity,” explained Brafman. Pregnant women were being pushed out of jobs, or leaving of their own accord, over requests for modest accommodations and confusion about what was required.

And while the job turnover also contributed to higher costs for employers, who had an incentive to retain capable employees, Brafman also points out that when women are pushed out of the labor force during pregnancy, it can be very hard to get back into the workforce. “The economic consequences can snowball for years,” she said. Such discrimination disproportionately affects the lowest wage workers and women of color, further exacerbating the discrimination and economic hardships they are already facing.

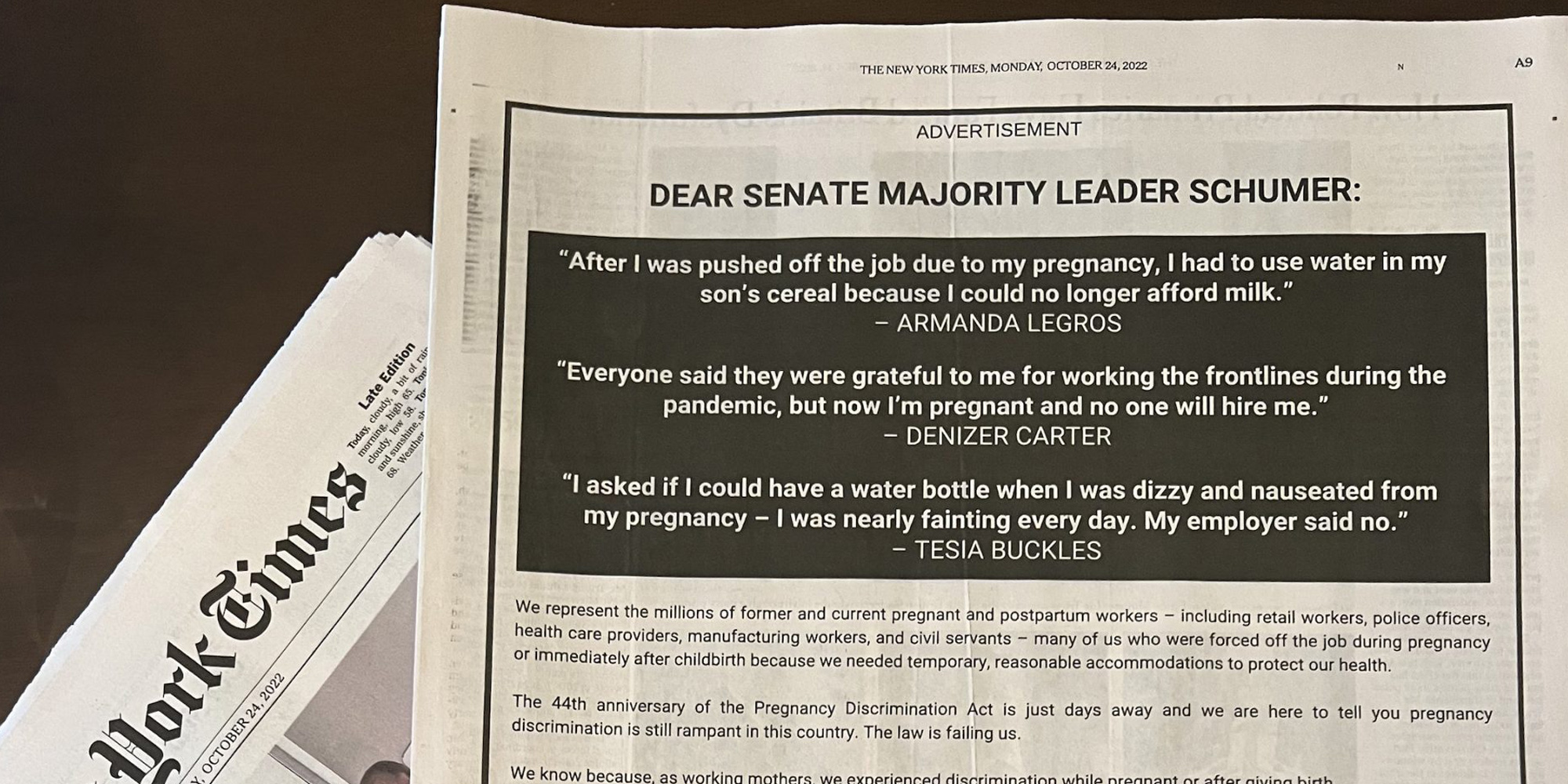

Both pieces of legislation appeared as amendments in the omnibus, a “nail biting experience” that Brafman said the coalition wasn’t sure would come to fruition until the last moment. The PUMP and PWFA bills had passed the House in October 2021 and May 2021, each with overwhelming bipartisan support of the Senate committee in May 2021 and August 2021, respectively, and it had taken community efforts and business community support. Additionally, 125 working mothers from 42 different states who had personally experienced pregnancy discrimination published a letter as a full page ad in the New York Times to bring PWFA to the floor for a vote. Similar advocacy efforts by groups that include the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee and many others, was required to get the PUMP Act over the finish line.

“It boiled over, it couldn’t be ignored anymore,” said Brafman. “The pandemic really awakened Congress to issues that working families were facing.”

But the work is far from over. “Passing the new federal law is the beginning, not the end,” says Brafman. An education and advocacy campaign will begin to work with employers, workers and the EEOC to educate people on why this law exists and how it can accommodate pregnant women. Employers need to understand how to comply with the law, just as pregnant women learn about their rights to basic accommodations, as enforcement mechanisms are put in place.

As with any other drastic legislative changes, it can take time to fully realize the effects. The bill provides protections for pregnancy, childbirth, lactation, related conditions, even allowing workers the ability to change their schedule for prenatal or postnatal appointments.

“This is a landmark civil rights bill. It is one of the biggest updates to our civil rights law in decades.This is a maternal health measure that will level the playing field for workers of color,” said Brafman. “The consequences of this will be very far reaching.”

Rebecca Gale

Rebecca Gale is a writer with the Better Life Lab at New America where she covers child care. Follow her on Instagram at @rebeccagalewriting, and subscribe to her Substack newsletter, "It Doesn't Have to Be This Hard."