Oregon is aiming to improve child care across the state—expanding access, boosting quality and building more sustainability into the system. It’s not a moment too soon. According to a recent survey, families are struggling to find high-quality, affordable care that meets their needs, and wait lists for care can be as long as three years. The longstanding, overlapping crises have immediate and long-term consequences for the economy and the health and well-being of Oregonians.

👉 Pre-Pandemic, Oregon Child Care Was Already Scarce (Oregon State University)

To achieve its goals, the state is enlisting the support of Oregon State University. As the state’s public, land-grant institution of higher education, OSU is committed to serving the people of Oregon. ELSI, the Early Learning System Initiative at OSU, is a vital new partner in the enterprise.

Megan McClelland, director of the Hallie E. Ford Center for Health Children and Families, says discussions about ELSI began in 2020 when the state’s Early Learning Division (then part of the Department of Education) requested a coaching framework for early learning professional development.

As McClelland and her colleagues planned, iterated and conducted interviews with stakeholder groups, more funding became available from a variety of sources totaling $14.4 million, and ELSI has branched out into other ways of improving the state’s workforce and system as a whole. In the midst of this metamorphosis, the division that sparked the initiative is undergoing a change of its own, becoming the Department of Early Learning and Care.

“It feels like we’ve been in charge of a startup for the last two years,” says McClelland.

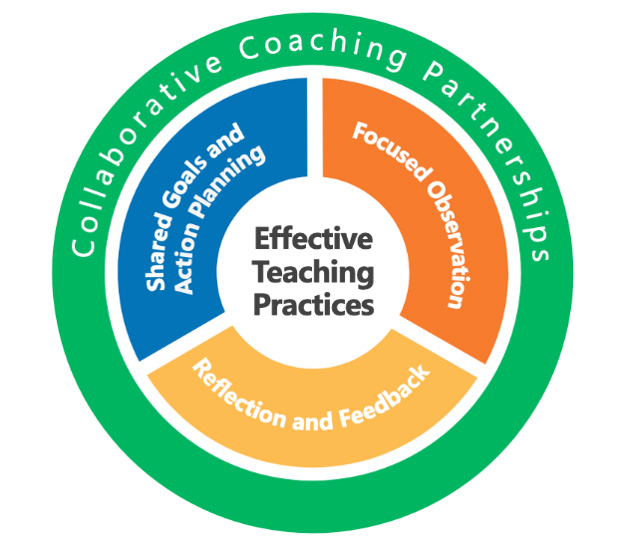

Professional development remains at the heart of ELSI. This includes Practice-Based Coaching, which, according to Patricia A. Snyder of the University of Florida’s Anita Zucker Center for Excellence in Early Childhood Studies, needs to be “cohesive and sustained over time rather than episodic, one-shot training. The content… should focus on explicit curricula, interventions, or sets of practices rather than general teaching methods such as lesson planning or instructional grouping methods.”

👉 Supporting Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices Through Practice-Based Coaching

Bridget Hatfield, associate professor at OSU’s College of Public Health & Human Sciences, helped to develop a mentor coaching framework to support the state’s existing network of early childhood coaches. She partners with a quartet of ELSI mentor-coaches, who fan across the state to work with about 120 coaches (about 20 of whom are employed by Oregon’s Child Care Resource and Referral Services)—who then partner directly with the state’s early education workforce. “This framework means there’s someone those educators can have reflective conversations with, whether it’s about how to be more intentional about using data or about their professional development.”

Hatfield, who started her career as an educator with a child care center in southern Indiana before undertaking graduate and postgraduate studies, adds that improving teaching practices is just one aspect of the mentor-coaches’ work, along with values such as equity and anti-racism. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) Professional Standards and Competencies and Elena Aguilar’s Coaching for Equity have been especially helpful for the mentor-coaches’ leadership journey. “The educators benefit the most,” she says, “when the coaches feel equipped and empowered.”

ELSI is also engaging with statewide partners, gathering and reporting data to inform and improve policy, and elevating the voices of parents and caregivers. This work includes developing communities of practice with coaches around the state, partnering with other statewide centers at Portland State University and Western Oregon University and analyzing statewide data to provide recommendations for increasing the quality of early childhood education in Oregon.

“Child care is incredibly local,” says Megan Pratt, OSU professor of practice. Child care solutions differ across communities. Some prefer mixed-age home-based programs, while others are looking for preschool center programs.

“Like a lot of other states,” continues Pratt, who worked as a child care provider before earning her doctorate. “Oregon is trying to figure out how to move from fragmentation toward a more cohesive system that works better for families and the workforce.” For example, a better system will help ensure that federal relief dollars—as well as state money from Oregon’s Preschool Promise program and Baby Promise pilot—flow to formal and informal providers more quickly and efficiently.

ELSI has engaged First Children’s Finance to provide business coaching to help connect the dots. The nonprofit organization delivers trainings and technical support to early child care centers and home-based providers. “We offer tools to help these businesses become sustainable,” explains Kari Stattelman, a business development consultant with First Children’s Finance. “That could be marketing, finance or record keeping. Some of them benefit by pooling resources through a shared services network. Others need help selecting and implementing a child care management system.”

👉 Child Care is a Small Business with Big Impact (First Children’s Finance)

Thanks to the Child Care Emergency Response Package, everyone in Oregon’s early education workforce is getting two $500 checks with no strings attached. Of course, the other half of successfully connecting providers and checks is ensuring that providers know about these opportunities and have the capacity to apply. First Children’s Finance helps providers overcome linguistic and other challenges that might prevent them from securing funds for which they are eligible.

To build the capacity of providers and the strength of the overall landscape, ELSI will incorporate additional strategies over time. “Design is never done,” McClelland states. “It’s a continual process, and we’re just beginning, but we’re already having an impact.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.