The Bank Street College of Education’s new Early Childhood Policy Fellowship got started this past September. The year-long, remote, no-cost fellowship is devoted to the creation of early childhood systems characterized by both equity and quality. Early Learning Nation magazine spoke to four of the 15 inaugural fellows, two in North Carolina, two in Minnesota.

Using Her Voice

Carol Orji grew up in Nigeria, where society was divided between the haves and the have-nots. “I had the opportunity to go to school, to ask questions, to thrive,” she recalls. “Not everybody had that.” The daughter of an educator, she has dedicated her own career to helping others gain access to educational opportunities in Wake County, N.C., where she perceives economic divides that remind her of her home country.

As Director of Early Childhood Initiatives at Wake County Smart Start, she manages a state-funded program for four-year-olds and a new, county-funded program for three-year-olds. “We had a thousand families that qualify for the new program, but only a hundred slots,” she says. When she ran into a county commissioner, she wasted no time offering to testify at a budget hearing to make the case for increased funding.

“The fellowship has made me more aware of how to use those opportunities, to use my voice.”

Teachers and families continue to be under stress, she reports, and behavioral issues remain at crisis levels. “Sending those children home does not help,” she asserts. “Whereas paying education professionals adequately, as well as ensuring that resources are made available to support the children in their care, could help reduce stress.” She also believes social emotional learning should be part of the basic curriculum for early childhood educators, along with cultural sensitivity and racial equity.

Even though she hasn’t met the other fellows in person, formal and informal Zooms have enabled her to know them and rely on them. She mentions a brainstorm that arose when someone in her accountability cohort was struggling with a boss. “We asked, ‘Have you done this? Have you done that?’—not telling her what to do, but helping her think through the process.”

The Children Are Watching

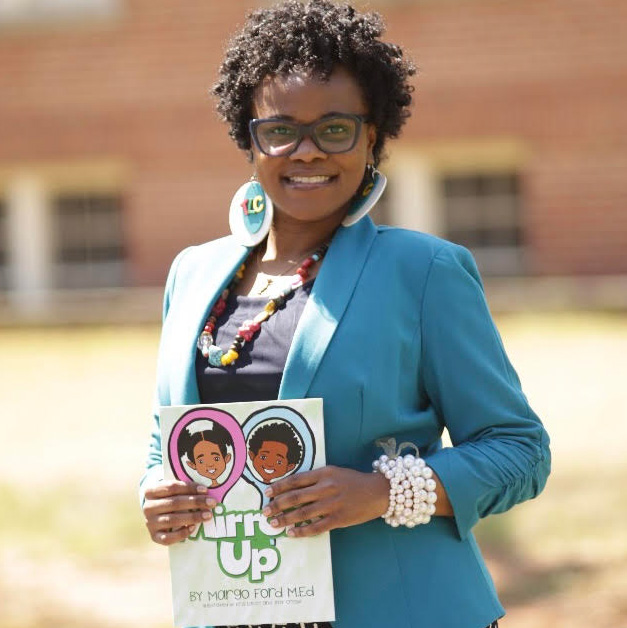

“Bank Street,” says Margo Ford Crosby, “brings me together with other individuals who are as passionate and purpose driven as I am.”

The daughter of a police officer and a social worker, Crosby is the director of Pre-K and Before/After School for the Alamance-Burlington (N.C.) School System’s Early Learning Community. She is also PTA President at the Early/Middle College at Guilford Technical Community College-Greensboro and author of a children’s book titled Mirror’s Up.

“I noticed how we were treated during Covid,” she recalls, “and saw colleagues getting sick and dying.” Showing up to community Zoom meetings in her personal protective equipment, she advocated for professionals making the sacrifice for children. The urge to organize and speak out has stayed with her, and the Bank Street fellowship is helping her to refine her tactics. Every fellowship session, she says, gives her something new to put in her newsletter or share at a staff meeting.

One of Crosby’s professional models is Dr. Sharon Contreras, former superintendent of Guilford County Schools. “She reminded us that the children are watching,” Crosby says. “The children are watching me in the classroom, at the grocery store. What are they seeing? Are they seeing us advocate for them?” This sentiment has stayed with her as she champions a holistic approach to early education that encompasses wellness as well as academics.

State and local policy is also high on Crosby agenda as she challenges standard ideas about achievement gaps and pushes for expanded access to opportunities in care and education. “I’m ready to get in good trouble,” she says, invoking the motto of the late Congressperson John Lewis.

Caution: Big Changes Ahead

Early in her career, Nikki Kovan followed in the footsteps of her mother, an early childhood teacher who became a child care director. “I really like young children and wanted to work directly with them,” she notes, “but my mother was very insistent that I not go into early childhood education as a teacher. She wanted me to be financially independent and not have to work multiple part-time jobs on top of teaching like she did.” The Institute of Child Development brought her from New England to Minnesota, and after she earned her Ph.D., she became a researcher at the Center for Early Education and Development.

Today, as Interim Director, Early Learning Services, in the Minnesota Department of Education, Kovan is striving to improve early learning environments through public investment in the teachers and providers who care for and educate children. She aspires to achieve pay for early childhood teachers and providers that is comparable to K-12 teachers, alongside equitable access to professional development and coaching.

The Bank Street fellowship functions for her as an informal network. “Every time I go to my fellowship,” she says, “the topic of the day has immediate application to something that’s happening at work, and I’m like, ‘Oh, I could use that tool to help lead my team around this thing that’s happening.’”

With big investments in the Governor and Lieutenant Governor’s proposed budget, and a slew of bills put forward by legislators in Minnesota, Kovan is braced for sweeping changes ahead for kids, families, and early care and education providers. (As of this writing, a bill raising child care assistance rates is advancing, as is a bill increasing investment in an early learning scholarship program, among others.)

She admits to both a degree of trepidation and some excitement about the prospect of implementing such measures. “If all of this passes at once,” she says, “it is going to be fast and furious, but has the potential to have a big impact on the early care and education system, and in particular, a big impact on those children and families that have been farthest from opportunity in Minnesota.”

Doing Big, Complicated Things

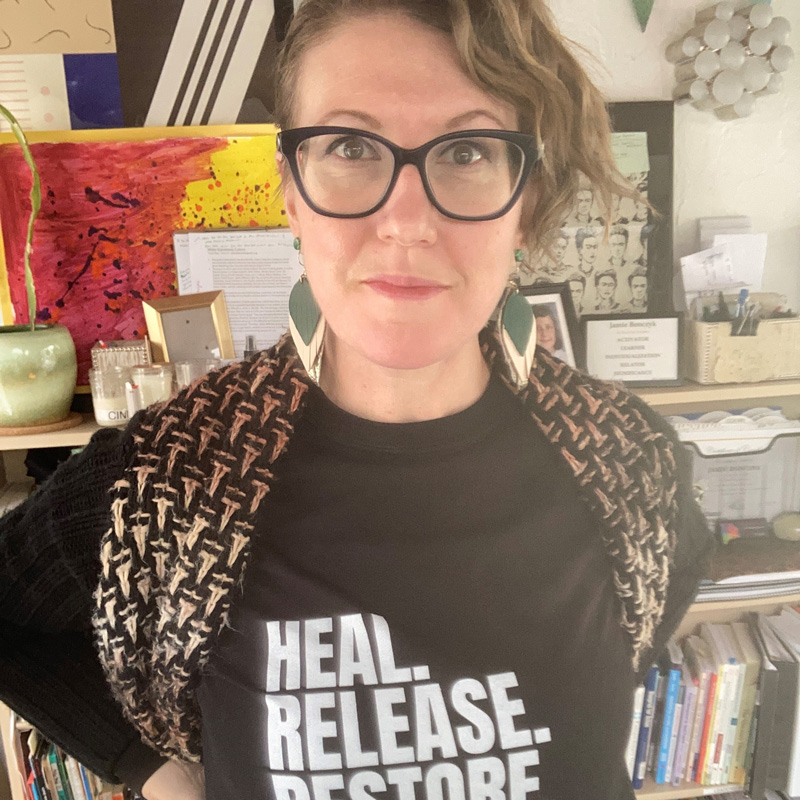

In the lifelong fight for educational equity, Jamie Bonczyk draws from her own personal experiences. In particular, she recalls being shamed publicly by her peers for needing a pink lunch ticket, indicating that her family received meal assistance. She also experienced firsthand systemic failures due to a childhood disability that became chronic because of a botched surgery. These experiences exacerbated an already tenacious temperament that she now sees reflected in her own daughter.

👉 Healing Out Loud: The Life-Giving Power of Story

“It’s helpful when you’re an adult if you want to do big, complicated things,” she says, “but they don’t tell you how challenging it is to parent a child like that.”

Now a program officer for 80×3: Resilient from the Start, an initiative of the Greater Twin Cities United Way, Bonczyk aims to create a region of trauma-sensitive child care centers. To ensure children, families and those who work in the field get the supports that they need, it is time to move away from what she calls “unfunded mandates” in the early childhood sector. She adds, “We must stop asking an underpaid workforce to serve as voluntary change makers.” It is time to fund early childhood education and care as a public good.

Bonczyk appreciates the way Bank Street approaches the fellowship as a true collaboration. “The experience is really co-designed,” she says. “They solicit our input at every opportunity. They want to push the work they’re doing so it works best for us.”

For Bonczyk, equity means policy change, not just awareness of the problems. Citing Rosemarie Allen and her Center for Equity & Excellence, she contends that “awareness is only halfway there.”

Mark Swartz

Mark Swartz writes about efforts to improve early care and education as well as developments in the U.S. care economy. He lives in Maryland.